Genes behind deadly heart condition found, scientists say

- Published

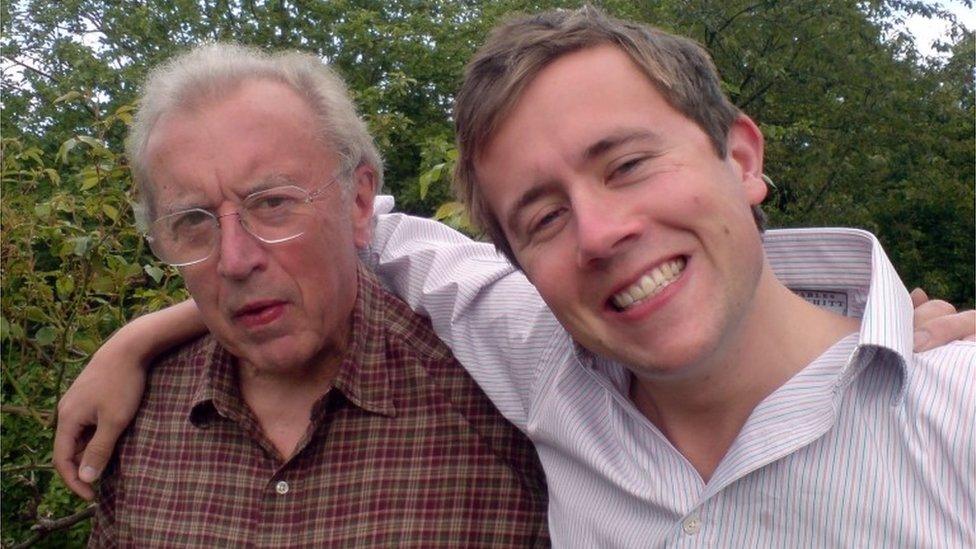

Scientists looked at the genes of people with pulmonary arterial hypertension to find out what was causing the condition

Scientists say they have identified genes that cause a deadly heart condition that can only be cured by transplants of the heart or lungs.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension kills 50% of those affected within five years, but little was known about what caused the condition in some people.

Now experts say they have discovered five genes that cause the illness.

The findings could lead to earlier detection of the disease and ultimately new treatments, researchers say.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) currently affects around 6,500 people in the UK and causes the arteries carrying blood from the heart to their lungs to stiffen and thicken, ultimately leading to heart failure.

It is often diagnosed in people who have other heart or lung conditions, but it can affect people of any age and in about a fifth of people there is no obvious cause.

The only "cure" is a transplant of the heart and particularly the lungs, but there is a waiting list for organ transplants and the body will often ultimately reject them, particularly in the case of lungs.

For this latest research, published in Nature Communications, external, scientists carried out the largest ever genetic study of the disease by analysing the genomes - the unique sequence of a person's DNA - of more than 1,000 PAH patients for whom the cause of the illness was unknown.

They found that mutations in five genes were responsible for causing the illness in these people, including in four genes that were not previously known to be involved in the disease.

In people with the condition these genes fail to effectively produce the proteins that are required for the structure, function and regulation of the body's tissues, researchers found.

Nick Morrell, the lead author of the paper and professor at the British Heart Foundation, told BBC News: "Identifying the nature of these new genes and mutations in the new genes tells you what causes the disease.

"It allows you to design and come up with potential new ways of treating the disease because you have really well-grounded knowledge about what's actually causing it in cases where you find these mutations," he explained.

'People should be more aware'

Wendy Callaghan was diagnosed with the condition five years ago

Wendy Callaghan, from west London, was diagnosed with PAH in 2013 after doctors became concerned about her persistent chest infection.

Her sister died from the condition 27 years ago at the age of 36, and her grandmother also died from a similar heart condition.

Wendy, who participated in the trial, has been told she has the genetic version of the illness and is now waiting to learn if her daughters and grandchildren have inherited the same deadly condition.

The 58-year-old said: "Even children can get it. People should be more aware of it and look out for the signs and persist with it if they think their child is not well.

"Especially as it does run in families, some people if they don't know they've got it could be passing those genes on to the next generation," Wendy added.

The research was part of a pilot study for the 100,000 Genomes Project, external - a huge initiative focused on understanding the genetics of cancer and rare diseases.

Prof Morrell said such genetic studies were helping to transform our understanding of rare diseases.

He said: "Often people with rare diseases go to lots of different specialists, everybody is scratching their head a bit, we don't know what the cause is, therefore it's hard to find a treatment for it.

"Now being able to [genetically] sequence people with rare diseases at scale allows you to push the genetics into the clinic and into the families, and it also gives you a cause for the disease which you can potentially do something about," he said.

Darren Griffin, professor of genetics at the University of Kent, who was not involved in the study, said the research was "one of the big successes" of the 100,000 Genome Project.

He said: "By studying the role of rare genetic variation in diseases, we come to a better understanding of the disease pathology itself, which can aid in early diagnosis and in tailoring treatment regimes."

- Published1 February 2017

- Published19 February 2016