Thalassaemia gene therapy trial shows 'encouraging' results

- Published

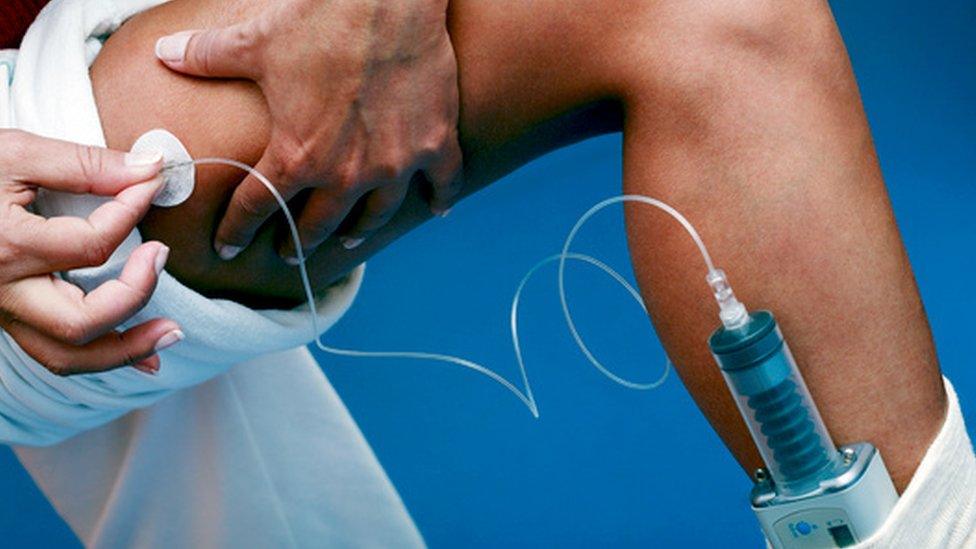

High blood iron levels from regular blood transfusions require treatment in patients with thalassaemia

Scientists say they are "excited" by the results of a gene therapy trial for the inherited blood disorder beta-thalassaemia, which reduced the need for blood transfusions.

In 22 patients, blood stem cells were extracted, treated and re-introduced to stimulate red blood cell production.

Fifteen patients were able to stop transfusions altogether while others needed fewer of them.

But experts caution that the long-term effects of the treatment are unknown.

Publishing their findings in the New England Journal of Medicine, the international team of researchers behind the study said the gene therapy - known as LentiGlobin - was safe and effective.

Only one patient had previously been successfully treated this way, by genetically correcting cells and transplanting them back into the patient.

'Open doors'

Lead researcher Alexis Thompson, professor of paediatrics at Northwestern University, said the results on this larger group of patients were "exciting" and "very promising".

"This approach may be effective. It has been safely done and should open doors for other diseases like sickle cell."

People with beta-thalassaemia, external - the most severe type of the condition - have inherited a faulty gene that affects the amount of haemoglobin produced in the body, making them very anaemic, tired and short of breath.

It mainly affects people of Mediterranean, South Asian, South-East Asian and Middle Eastern origin.

They need regular monthly blood transfusions throughout their lives.

In this study of 22 patients around the world treated with the gene therapy:

Three of the nine patients with the most severe form of the disease stopped transfusions

The need for blood transfusions was reduced by 73% overall in those patients

12 of the 13 patients with a less serious form of the disease no longer needed transfusions

The researchers also said there were no safety concerns after the treatment in the short term.

'Hugely expensive'

Irene Roberts, professor of paediatric haematology, at the University of Oxford, said: "Reducing or stopping transfusions is important for patients with thalassaemia because they are a double-edged sword- essential for survival but also responsible for life-changing, life-shortening side-effects.

"This means that the results are very encouraging."

But she said it was still to be shown whether the therapy could be used to treat the nearly 300,000 beta-thalassaemia patients worldwide.

Prof Douglas Higgs, also from Oxford University, pointed out that not all the patients had become free of transfusions and there was still little known about the long-term effects of manipulating the genome of stem cells in this way.

He said: "A major question hanging over this approach, which is hugely expensive, is whether this procedure will ever become clinically possible in developing countries, where the majority of these disorders of haemoglobin occur."

- Published28 March 2011