The NHS needs more money - but how much?

- Published

There is now a consensus that the NHS needs more money.

The prime minister has acknowledged that and called for a new long-term funding plan. But how much? That is the really tricky question facing the government as it tries to meet expectations.

An authoritative report has come up with a first stab at an estimate of what will be required in England over the next decade and beyond.

And the fact it comes from experts from the two main parties at Westminster gives its findings added weight.

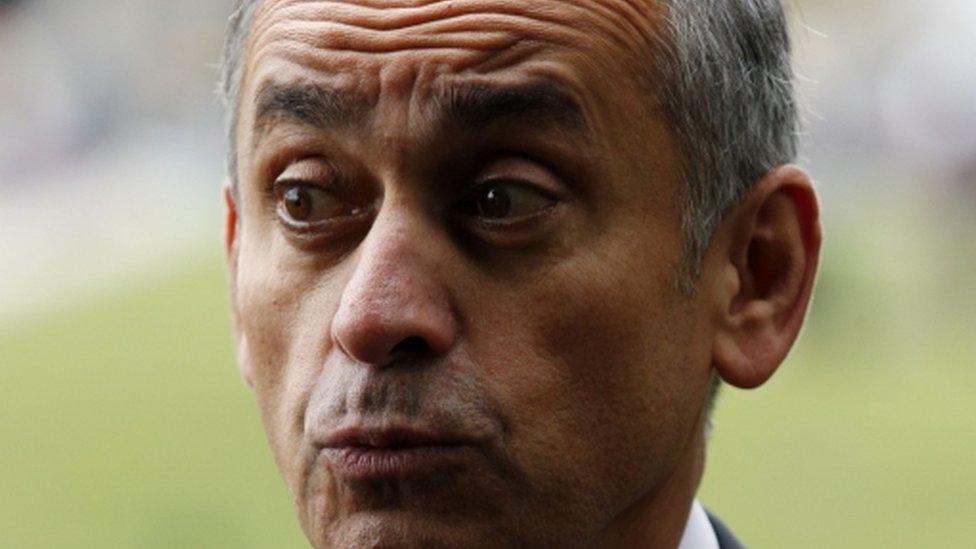

Lord Darzi, an eminent surgeon, was a Labour Health Minister under Gordon Brown and Lord Prior, who now chairs a hospital trust, served as a Conservative Health Minister in Jeremy Hunt's department.

The report, external, produced by the think thank the Institute for Public Policy Research, is being read at the highest levels of government.

Lord Prior's involvement means it cannot be ignored by Downing Street. And Lord Darzi's admirers include Jeremy Hunt.

They have certainly come up with some big numbers - an extra £50bn a year above inflation needed for the NHS by 2030 and £25bn a year more in productivity savings.

This is equivalent to a real-terms increase of 3.5% per year over the next decade. Social care, say the authors, will need £10bn more a year by 2030 just to maintain current levels of care.

These are figures for England - if adopted by the government at Westminster, they automatically generate increases for Scotland and Wales under the usual formula.

They have come up with these figures after modelling the expected increase in demand for patient care.

Demographics are among the key factors, with a 33% predicted rise in the number of people over the age of 65 by 2030.

Increasing numbers of elderly patients with multiple long-term conditions will need to be looked after across the health service.

A separate report by the King's Fund, external think tank has highlighted another cost pressure, namely the pharmaceuticals budget.

This shows that total NHS spending on medicines in England has been growing at about 5% per year since 2010, well ahead of annual health service funding allocations.

The report notes that this reflects a higher number of people receiving care and a wider range of treatments available.

Raising the cash

So where will the money come from? Although they do not say so explicitly, Lord Darzi and Lord Prior are suggesting it will have to come from higher taxation.

Lord Darzi says taxes must rise

Raising £50bn implies increases of 7p in the pound on income tax or National Insurance or a mixture of both.

The other option is higher borrowing, though that may be hard to accommodate in current public finance policy.

A second report later this year will spell out more clearly how the revenue might be raised.

This is difficult territory for the government.

On the one hand, ministers have promised a long-term funding plan for the NHS and will want to come up with credible figures.

But on the other, they will be loath to get pulled into commitments on taxation well ahead of a general election.

Jeremy Hunt will want to ensure there is a realistic stream of funding inked into the strategy - but he knows the Chancellor, Philip Hammond, will have firm views on tax-and-spend policy.

Prevention and early intervention will be elements of the new plan.

A report from Pro Bono Economics illustrates one example, external.

It found that mental-health counselling in primary schools, provided by the charity Place2B, could generate significant economic benefits by improving outcomes for children.

Reducing smoking and depression in later years will save money for the NHS.

In other words, spending now on prevention will reap bigger savings in the longer term.

Lord Darzi and Lord Prior believe the NHS is sustainable and a taxpayer-funded system is more effective than insurance-based models, which are more costly to administer.

But they say reforms and new thinking are required and, crucially, a significant increase in funding.

That amounts to a gauntlet being thrown down at the door of Number 10.