Breast screening: Is the NHS programme working?

- Published

Patricia Minchin says her cancer may have been spotted earlier had she received a screening letter

Scientists are seeking to reassure women who may have missed out on breast screenings that the cancer-detecting test is not a magic bullet and is not itself without risks.

Throughout the UK, women aged 50 to 70 should be automatically invited to have a mammogram every three years, provided they are registered with a GP. Women can be invited for their first scan up to three years after they first become eligible - so, up to the age of 53.

Although women over 70 aren't routinely invited for breast screening, they are still able to request a scan if they feel they would benefit.

But a computer error in 2009 has resulted in 450,000 women in England not being invited to their final breast cancer screening.

Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt said it was estimated that up to 270 people could have had their lives shortened as a result.

Mammograms are currently the best available tool for detecting breast cancer early and are linked to a reduction in deaths from the disease, although not a large one.

But, like most medical procedures, they can carry risks as well as benefits.

A study in 2012 estimated that women who attend breast cancer screenings are 20% less likely to die , externalof breast cancer than those who don't. However, a later study has suggested, external the benefits are smaller - more like a 10% reduction to women's relative risk of dying of the disease.

The 2012 study says there's also a group of women who are "over-diagnosed" - in other words they receive treatment for a cancer that "would never have caused problems" if it had not been picked up in screening.

More than 10,000 people a year die of breast cancer - a third less than in the 1970s.

A comprehensive national breast screening programme was introduced in the late 1980s. But it's difficult to attribute any improvements in mortality to this, as general improvements in awareness and treatment were taking place at the same time.

The NHS estimates that its screening programme saves about one life for every 200 women who are scanned for breast cancer, adding up to about 1,300 lives saved each year in the UK.

But about three in every 200 women screened are diagnosed with a cancer that would never have become life-threatening, equating to about 4,000 women each year being offered unnecessary treatment.

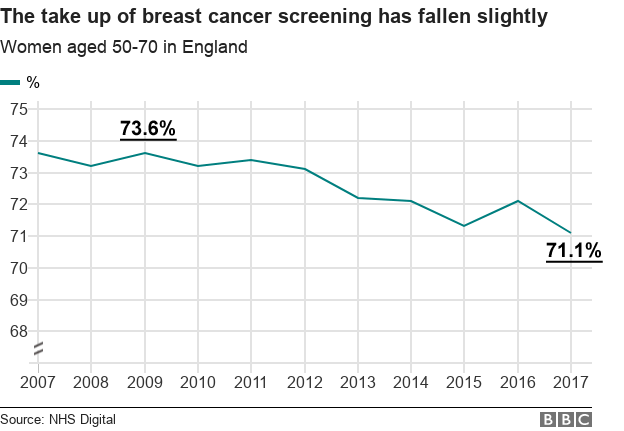

In England, where the error took place, 71% of invited women attended a breast screening last year.

This was the lowest take-up in at least 10 years, although only by a small margin. Until 2012, take-up of the scan was consistently around 73%.

This take-up rate is similar throughout the UK and above average compared with 32 other major global economies.

There is also some risk attached to receiving the X-ray itself, but these risks are thought to be outweighed by the benefits of early detection.

Women who are diagnosed with breast cancer at an earlier stage are more likely to survive and less likely to need surgery to have part or all of their breast removed.

'Weak evidence'

University of Cambridge statistician and risk expert Prof David Spiegelhalter said: "It's a tragedy for any particular woman to have missed her cancer being detected earlier because of an administrative error."

However, he added that "there is only weak evidence that screening helps prolong life, particularly for older women".

He stressed that the figure of 270 women who may have had their lives shortened was an estimate and did not capture those whose life expectancy was lengthened by not having unnecessary radiation treatment.

Dr Nora Pashayan, from University College London, said: "Breast cancer screening prevents deaths from breast cancer in some women. On the other hand, not all cancers picked up by screening would result in death prevention and others won't be picked up by screening at all."

- Published2 May 2018

- Published3 May 2018

- Published2 May 2018

- Published30 October 2012