Why is there stigma around male baldness?

- Published

- comments

Actor James Nesbitt credited his hair transplant for boosting his acting career

Scientists say a drug normally prescribed for osteoporosis could potentially lead to a new treatment for hair loss. But why is there stigma around male baldness? And why do men try to "cure" themselves of it anyway?

Whether it's actors Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson and Jason Statham or business titans Jeff Bezos or Goldman Sachs chief executive Lloyd Blankfein, there is no shortage of men in the spotlight who are bald.

Forget wigs, hairpieces or other attempts to hide their baldness, all of them have shaved heads that draw attention to, rather than disguise, their sparse locks.

And it seems there may be good reason to embrace baldness rather than cover it up.

Some studies have indicated that men with shaved heads are perceived to be more masculine and dominant than their full-haired counterparts, external.

The video blogger Perry O'Bree, who started losing his hair at the age of 20 and recently took part in the BBC Newsbeat documentary Too Young to go Bald, says baldness is something we should "embrace and celebrate".

Yet for many male pattern baldness is a source of emotional distress.

Actor James Nesbitt said his hair loss had affected his confidence and career and credited his subsequent hair transplants with helping him to get better roles.

"It was something I struggled with. And that was probably the vanity in me," he said at the time.

So why does hair loss often hit men so hard?

David Fenton, of the British Association of Dermatologists, says representations of physical perfection in the media lead many men to seek self-esteem in their appearance.

"People create confidence and self-esteem from it, and when they lose even a little bit, if their character and confidence is based on that, they're going to have severe emotional and psychological impacts," he says.

But is the pain some men feel about balding new or has it always existed?

Magic potions

Actors talking about hair loss affecting their confidence and ability to get parts sounds like a distinctly modern issue for our image-conscious times.

But men's concerns about balding appear to go back hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

In the Bible, two bears mauled 42 boys after they mocked the prophet Elisha by calling him "Baldy", external.

Baldness was also said to be an obsession of Julius Caesar, who reputedly tried all manner of things to get his hair back.

Elsewhere, supposed cures for hair loss abound in history.

The Vikings are said to have used a lotion of goose guano. The ancient Greek medic Hippocrates's "cure" involved pigeon droppings mixed with horseradish, cumin and nettles.

And a rather gruesome 5,000-year-old Egyptian recipe suggested blending the burned prickles of a hedgehog immersed in oil with honey, alabaster, red ochre and fingernail scrapings.

What is male pattern baldness?

Also known as androgenic alopecia, it usually initially involves the loss of hair from the front and sides of the scalp and progresses towards the back of the head

It is most common in white men, happens less often in black men and later and more slowly in Asian men

It affects about 80% of white men who are 70 or older

It is caused by a combination of genes and the way the body responds to testosterone

Source: NHS/NICE

But where does man's preoccupation with hair loss stem from?

"It depends on the society, but one of the important communications that hair gives - the style, the colour, the presentation - it's one of the most powerful means of communication," says Dr Fenton.

"When you lose hair, one of the immediate messages is that you're perhaps ageing. And usually this is something people don't want. It goes along with superficiality and appearance in society."

Scientific breakthroughs

It wasn't until the 1980s that the first real breakthrough in the science of hair loss treatment took place, when scientists discovered the blood pressure drug minoxidil caused hair growth as a side-effect.

This led experts to look for ways to repurpose the drug to treat hair loss, eventually creating a lotion that could be applied to the scalp.

The next major treatment came when scientists found that some bald men given tablets aimed at preventing the prostate from enlarging started to re-grow their hair.

The drug, now sold as finasteride, blocks the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone - a process that happens in people who are balding.

The two drugs are the most common treatments for male pattern baldness in the UK.

But neither is prescribed on the NHS. And they're expensive. They're also inconsistent, Dr Fenton says.

In some people, they don't work at all. In others, they slow down or stop hair loss. While in the lucky ones, there can be some hair re-growth.

But any benefit will eventually reverse once treatments are ended.

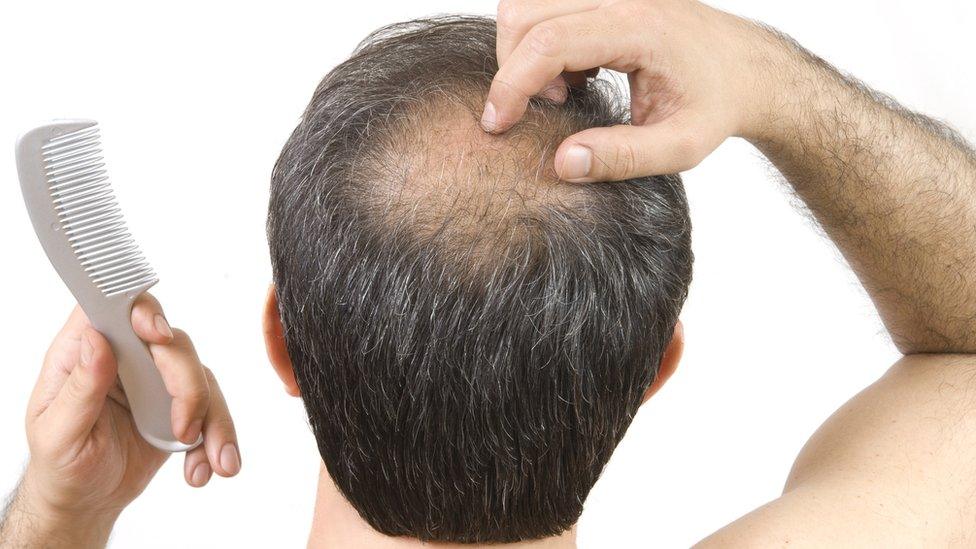

Hair transplants involve moving hair from one part of the body to the area of baldness

Hair transplants - used not only by James Nesbitt but also footballer Wayne Rooney - have become increasingly effective, to the point that they are often undetectable when done by a good surgeon.

They work by transferring hair from another part of the body to the balding area.

But they're also costly, ranging from £1,000 to £30,000 for the most comprehensive transplants.

And they are generally better suited to older men or those whose hair loss has stabilised.

One potential treatment showing promise is the injection of plasma-rich platelets into the scalp to stimulate hair growth. Though more studies on its effectiveness are needed, experts say.

But will science reach the point in our lifetimes where it will be able to "cure" baldness?

Actor Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson is bald and admired for his brawn

Dr Fenton believes it will be possible to reverse balding, at least to some extent, in most people eventually.

But because baldness is a normal physiological process, rather than a disease, such a treatment would need to be taken continuously to prevent its effects wearing off.

"You can't cure something that is a normal physiological happening," he says.

"You're fighting your genetic programming. And to do that you have to do it forever or until you don't care."

But is baldness something that even needs to be "cured"?

Dr Fenton says the shaved look adopted by Dwayne Johnson and others is an approach that would best suit a lot of men.

"It's a very convenient way of covering up that you're thinning in one area and not another," he says.

"That's one way that some people cope satisfactorily. And that may be enough for them."

Perry O'Bree says attitudes to baldness have improved.

"The more you talk about it, the better it gets," he says.

"At first, it's a bit of a shock to the system. But once you discover that so many other people your age have gone through a similar thing, it's not so bad.

"It's part of a life-cycle."

- Published9 May 2018