Peru's children hit by metal poisoning

- Published

Wilma and Marcus are worried about their daughter

Wilma Tovalino and Marcos Castaneda live by a mine in Cerro de Pasco, a Peruvian city high in the Andes mountains.

Their daughter began to complain of pain in her feet, so they took her to the local clinic.

She then began to have uncontrollable nosebleeds.

When she was 11, Shirli Castaneda Tovalino was taken to a children's hospital in Lima, where she was diagnosed with leukaemia.

She had 19.8 micro-grammes per decilitre of lead in her blood.

Her parents believe that pollution from the mine is to blame.

The government of Peru has declared a "health state of emergency" in 12 districts of Pasco because dangerously high levels of lead, arsenic, aluminium, and manganese were found in local water.

Lead, arsenic and mercury were also present in the soil.

But the government has not said what the source is of these metals in the environment.

Irma and Jhan in front of the mine

Jhan Francis Jesus Mauricio Estrella is 12 years old. His bones ache. When he walks, his right knee hurts.

His mother, Irma Estrella, says ultrasound and X-rays show his nerves appear to be paralysed, making it difficult to move his joints.

He too has lead in his blood.

Jhan and Shirli are among 45 children with serious illnesses from Cerro de Pasco who have been sent for treatment in Lima by the ministry of health.

Many other children have been experiencing nosebleeds and headaches.

Symptoms of lead poisoning in children:

irritability and fatigue

loss of appetite and weight loss

abdominal pain

vomiting

constipation

hearing loss

developmental delay and learning difficulties

The regional health authority of Pasco says that 20% of the people it surveyed had more than 10 micro-grammes per decilitre of lead in their blood, a level it regards as unsafe.

The World Health Organization says that no amount of lead in blood can be regarded as safe.

Maruja Silvia is responsible for coordinating the Pasco health authority's response to heavy metal contamination.

Irma shows the water supply in her backyard

She says: "Heavy metals, in particular lead, are causing neurological problems in the population. Many children are being affected; they are showing evidence of neurological and haematological problems."

The health authority says the causes of the illnesses are mixed: in this mining area, there are naturally occurring metals in the soils. Poor sanitation is another factor.

However, Maruja Silvia, is convinced that mining plays an important par. "It's certain that the problem for a long time has been mining activity," she says.

But the problem of metal poisoning is not confined to Cerro de Pasco.

Amnesty International has published an investigation into two other areas in Peru - Espinar and Cuninico - where locals also complain of illnesses related to metals in their blood.

Amnesty is calling for the government to carry out a nationwide study of the sources of contamination.

Porfirio Barrenechea, the National Ombudsman's representative on mining issues, agrees the state needs to investigate.

He says: "We can't generalise and say it is only the mining companies that are generating this contamination, we need to look at it case by case. And for this we need a specialist technical study that attributes responsibility."

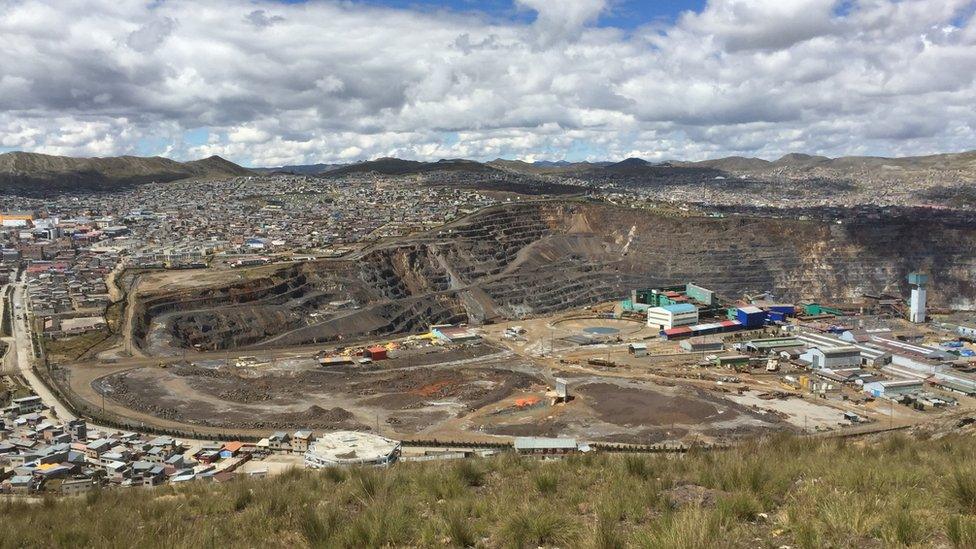

Cerro de Pasco: mining is a vital part of the Peruvian economy

Mining is Peru's most important industry, accounting for most of its exports.

The main mine in Cerro de Pasco, which yields silver, zinc and lead, is run by the Peruvian company Volcan.

The company's chief executive, Ignacio Rosado, says Volcan is now extracting metals only from existing stockpiles in Cerro de Pasco and is no longer mining new metal from the pit.

It constantly monitors the air, soil and water quality and is confident no contamination is coming from Volcan's operations, he says.

Glencore, the Anglo-Swiss mining giant, bought a majority of shares in Volcan last year.

In a statement, Glencore said it had been working closely with Volcan's management team to develop their environmental management programmes to align with Glencore's health safety and environment compliance programmes and wider best practice standards.

Pro-government MP Gilbert Violeta says: "It is not true that in all cases contaminated water comes from mining waste.

"There are many cases where it does - but that is because these are old mines. The majority of these old mines have either been closed already or are in the process of being shut down.

"The new mining projects we have in Peru, in general, are very careful about how water is used."