NHS 70: How have hospitals changed for children?

- Published

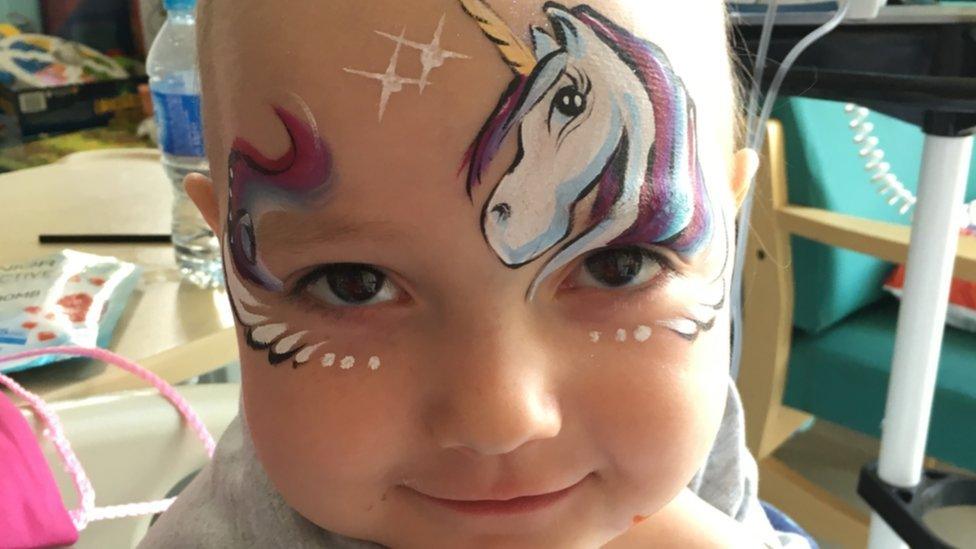

Ziggi Thompson is being treated for leukaemia

Ward 84 at the Royal Manchester Children's Hospital looks after young patients with cancer and leukaemia.

It's home from home for four-year-old Ziggi Thompson. She has leukaemia and is having intensive chemotherapy.

Like most of the children here, she has lost her hair and is wheeling around a portable drip.

She's also very excited.

When Ziggi grows up, she wants to be a superhero.

Batman, Superman, Spiderman and Black Widow are on the ward, giving the children high fives and "superhero fist-bumps".

The superheroes give children on the ward a lift

Andy, also known as Manchester's Dark Knight, says his group comes to make the children smile. He tells parents he's a crime fighter by profession, as he's a security officer at the Arndale Shopping Centre.

The children are delighted, laughing and chatting to the heroes. They barely notice as nurses do observations and change medications.

This is the largest single-site children's hospital in the UK. It has facilities for patients from birth to 18 years old.

There are toys on the rooftop garden, colourful playrooms and teen zones that look like student unions.

Ziggi's favourite part of her ward is the school room.

She was diagnosed four months ago, and initially spent five weeks in hospital. Now, she is here every other week.

Emily Pedrazzini sleeps next to her daughter on the ward

Her mum, Emily Pedrazzini, is by her side the whole time.

Every night, she sleeps on a pull-out bed next to Ziggi's hospital bed. She stays with Ziggi, while her husband looks after their six-year-old son, Zach.

She says she has to mentally prepare herself every time they come in - "knowing that I don't leave the room for a whole week, I don't get to see my son, I don't get to take him to school".

But, she says, it's become part of her normal life now. "Everyone is in the same boat. The kids play. And you get into your daily routines," she says.

A children's ward in 1948

This is a far cry from paediatrics in 1948. Back then, parents were allowed to visit children perhaps once a week.

Andrea Merrall was Ziggi's age at the time. She had a long stay in hospital with tuberculosis.

She says she used to scream and shout when her parents left. Eventually, she made such a fuss that her parents were banned from coming in at all.

She remembers feeling "isolated".

"I hated them leaving me," she says. "And I'm sure they must have hated leaving me too."

Andrea as a young girl (left) with her family

Stephanie Snow, a historian from the University of Manchester, is working on NHS at 70: The Story of Our Lives, a social history made up of memories from staff and patients.

She says former child patients have told her about frightening ambulance trips to hospital without their parents.

Others remember being treated on wards with adults, or being kept in quarantine if they had infectious diseases such as scarlet fever.

Ms Snow says treatment was often painful too. Some patients were injected with penicillin straight into their muscles, possibly several times a day.

Rights of the child

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) president Prof Russell Viner says: "Paediatrics was born in the NHS. And that's something worth celebrating.

"From cancer survival rates and gene therapy to vaccine development, we've come a long way in the last 70 years, especially in terms of children's rights."

But he is also calling for a "renewed focus on children".

"We need to deliver healthcare for children and young people that's fit for a modern NHS," he says.

"As the NHS turns 70, we have fresh opportunity to protect the health of future generations. So, let's prioritise child health and help make that happen."

We want to hear your stories and memories of the NHS past and present.

Have you been a patient or have you worked there? Share your memories with us by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also contact us in the following ways:

You can also contact us in the following ways:

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

WhatsApp: +44 7555 173285

Text an SMS or MMS to 61124 (UK)

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy