Ebola: How a killer disease was stopped in its tracks

- Published

A health worker monitors the temperature of a traveller from the DR Congo

One of the world's deadliest viruses, Ebola kills up to half of those it infects. But despite appearing to have all the hallmarks of a potential epidemic, the latest outbreak developed in a very different way.

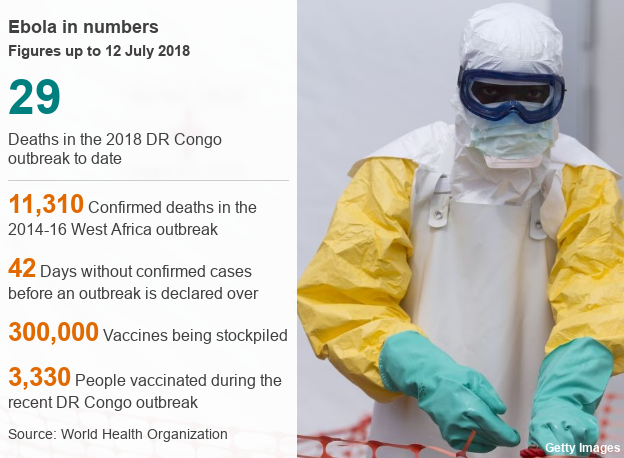

It was the ninth Ebola outbreak to hit the Democratic Republic of Congo in a decade, killing 29 people, external and leaving at least 60 children orphaned.

While one death is too many, the West Africa epidemic of 2014-16 claimed more than 11,000 lives and it is hoped that later this week the most recent outbreak will be declared officially over by the World Health Organization.

The relatively small number of deaths follows the use of an experimental vaccine, which may have saved hundreds, or even thousands of lives.

Fragile health system

Although the outbreak began in a remote area, there was a real danger that large numbers could be infected.

It appeared close to neighbouring Central African Republic and the Republic of Congo - a vast area with a great ebb and flow of people and a fragile health system. It is also an area linked by river and road to the capital Kinshasa - home to 10 million people.

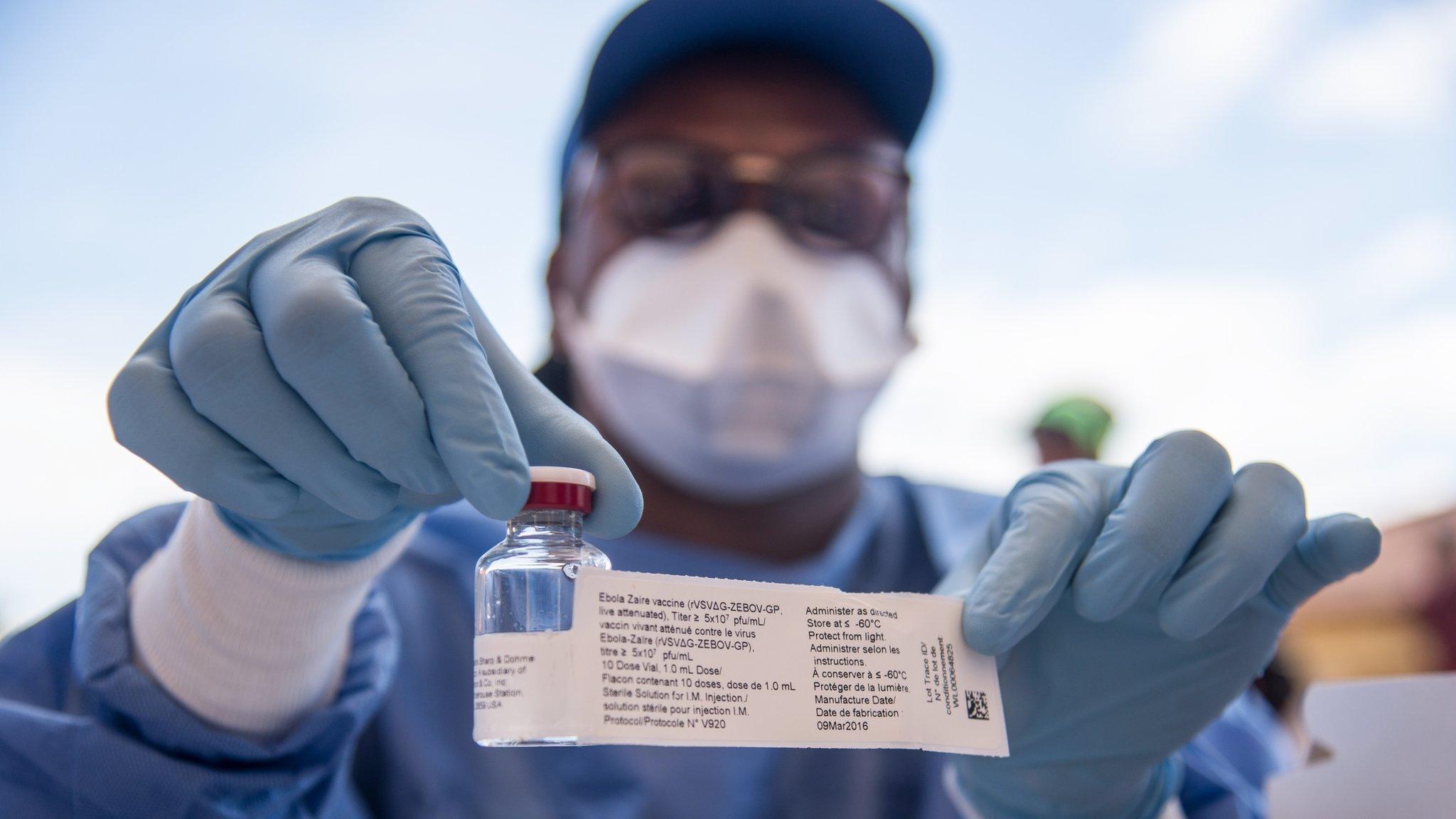

The vaccine used, known as rVSV-ZEBOV was already in development during the 2014-16 epidemic. But by the time its effectiveness had been proven, external, the outbreak was already waning.

When the virus returned in 2018, it could be quickly deployed, once the DRC government had approved its experimental use. This vaccine is designed for use against the Zaire strain of Ebola, which caused both this outbreak and the previous one.

Scientists and health workers set to work tracking all potential transmissions since the first case had been reported.

Front-line health workers, people in contact with confirmed Ebola cases, and their contacts all needed to be given the vaccine.

However, keeping the vaccine safe and making sure it reached the right people was not a straightforward task.

The vaccine must be kept extremely cold, at minus 70C.

This is difficult and expensive to do in a remote environment with unreliable electricity. Alongside the vaccine, fridges and generators had to be flown into the region by helicopter.

Isolation and treatment facilities had to be built, mobile laboratories set up and local laboratory technicians trained to test samples and confirm cases of Ebola.

Gaining consent

For the vaccine to be effective, it had to be given to the right people.

Health workers spoke to patients, their families and the wider community to dispel rumours, build trust and avoid panic.

This, they explained to community leaders, was not a mass campaign.

Vaccinations were given to the Ebola patient, plus a "ring" of friends, family and contacts - as well as healthcare workers and people involved in burials. All had to give their consent.

Identifying and finding all the people suspected Ebola patients had been in contact with was a major challenge because of the location.

Health workers had to travel by motorbike to places where there are no paved roads.

Despite these challenges, there has been high uptake rate and an estimated 98% of those eligible were vaccinated.

What is Ebola?

Ebola is a viral illness that kills between 30%-50% of the people it infects

Initial symptoms include sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain and a sore throat

Subsequent stages are vomiting, diarrhoea and - in some cases - internal and external bleeding

Ebola infects humans through close contact with infected animals, including chimpanzees, fruit bats and forest antelope

People are infectious as long as their blood and secretions contain the virus, which can be for up to seven weeks after they recover

Co-ordinated attempt

Health visitors travelling by motorbike through a remote area of DRC for a follow-up meeting with a contact

While the vaccination may have helped to save lives, better public health measures also played a crucial role in containing the outbreak.

Treatment centres and isolation zones were set up to reduce the spread of the virus and face-masks, gowns and gloves were used.

Safe burial practices also helped to limit transmission of the virus, as did screening of passengers at international and domestic ports and airports.

There has also been work to reintegrate survivors with their community because in former outbreaks survivors were sometimes ostracised by their families and neighbours.

Lessons for the future

In the three months since the outbreak began, more than 3,000 people in the region have been vaccinated.

As a result of its use - and the other precautionary measures - the epidemic is likely to end quicker than might have been expected.

But unfortunately this isn't the end of the road for Ebola, as we know it is a disease that will continue to appear in future.

Two years after it was first tested, the vaccine still works, but we don't yet know how long-lasting the protection will be.

More than one Ebola vaccine is needed, so we're not reliant on just one manufacturer.

It would also be helpful to have options for different situations - such as a single shot vaccine for quick protection and booster vaccines when there isn't an outbreak.

Researchers need to find out more about what works and why, so more lives can be saved.

To do that, we need to stop thinking of these outbreaks as isolated events - introducing a long-term programme of research and response into every Ebola outbreak.

And while Ebola is high profile, we also need to remember it isn't the only disease that could lead to an epidemic.

DRC is facing a worrying outbreak of polio that has paralysed 29 children and there are outbreaks of Lassa Fever in Nigeria, external and the Nipah virus in India, external.

It's impossible to predict what the next epidemic will be, but we can be better prepared.

At-risk countries need tools and support to strengthen their health systems and monitor disease, so that they are ready before an outbreak and can save as many lives as possible.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Josie Golding is the Epidemic Preparedness & Response Lead at the Wellcome Trust, external, a global charitable health foundation. Follow her at @BeakerH, external

The Wellcome Trust announced an initial fund of up to £2m to support a rapid response to the most recent Ebola outbreak, external in DRC.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie