Are women turning their back on the pill?

- Published

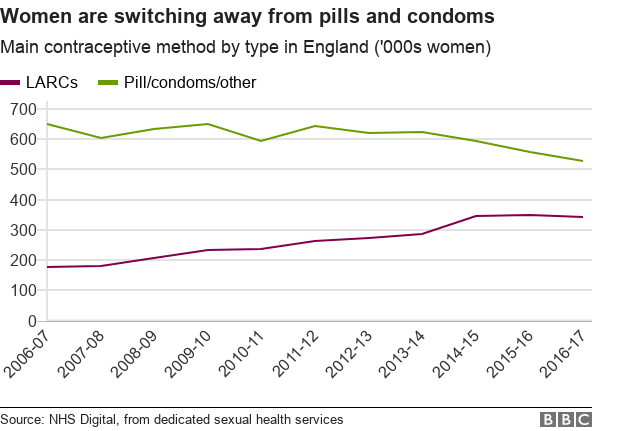

More women than ever are ditching the pill and condoms in favour of "long-acting reversible contraceptives", including the implant or coil. And younger women are the biggest adopters, according to figures from the NHS in England.

In 2007, 21% of women in England accessing contraception through dedicated NHS sexual health clinics chose some kind of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC). By 2017, this had almost doubled to 39%.

The LARCs include:

copper coil or intrauterine device (IUD)

hormonal coil or intrauterine system (IUS)

implant

injectable contraceptive

While oral contraceptives like the pill remain by far the most common single type of contraception - used by 44% of women accessing contraception through sexual health services - their use has fallen in the last 10 years. Prescriptions through primary care services including GPs have also fallen.

So why are more women seeking alternative forms of contraception?

From around 2010 onwards, the NHS in England made a concerted effort to increase awareness of long-acting contraceptives and to train more staff to fit them.

But as more women become aware of a wider range of options, more are asking for longer-term and non-hormonal options, says Dr Anatole Menon-Johansson, of Guy's and St Thomas' hospital and the young person's sexual health charity Brook.

"The most effective form of marketing of contraception is peer to peer, by word of mouth. There's a 'cascade' effect, where people hear about it from their friends who've had a good experience, then more people ask for it," he says.

Rosa, a 25-year-old now living in Spain who has switched to the coil, said: "I wanted a more permanent form of contraception that I didn't have to think about."

While Sara, 27, switched because: "With the pill, it's a drama. You have to get a new prescription, you forget, and then you run out."

And running out is the most common reason women will become pregnant while relying on the pill as contraception, says Dr Menon-Johansson.

IUDs and IUSs are inserted into the uterus and release either copper or hormones to prevent pregnancy

He wants LARCs use to become more widespread still, because he says they are far more effective than "user-dependent" alternatives like condoms and the pill - especially when you look at typical use.

While in theory the pill is more than 99% effective with perfect use, with typical use that falls to about 91%, according to the NHS.

This is just regarding pregnancy prevention - condoms remain the only option to protect against most sexually-transmitted infections.

The Pearl Index is a measure of the effectiveness of contraception with typical - including incorrect - use.

According to that:

using the implant, one in every 2,000 women will become pregnant

with an IUS it is one in 500

with an IUD it is just under one in 100

about one in every 10 women will become pregnant while relying on the pill

But Sara reports having another common contraception concern, too: "I was worried about my mental health," she says.

"I worried it was to do with the pill. I asked my doctor but they said no, it won't do that."

In recent years, concerns have been growing around the link between oral contraception and depression.

More women participating in a 2016 study who were taking the pill were diagnosed with depression for the first time over a 13-year period than those who were not.

However, the researchers could not prove causation and professionals still stress that there is no evidence for a causal link - although the NHS does list "mood swings" as a side-effect of the combined hormonal pill, which contains both oestrogen and progesterone.

Dr Menon-Johansson says he fits lots of IUDs for women who want something that is hormone-free, often because of mental health concerns, although again he emphasises that there is no clear data to link the two.

For many women in their 20s, hormonal contraception has been part of their routine since they were teenagers. And some feel they have never experienced their adult life without taking something that is potentially mood-altering.

Gabrielle became aware that she did not know what her mental state was like without taking hormones, having been on the pill since the age of 18.

"I was more just wondering what it was doing to me and what I'd be like not on it," she says.

She now wants to try a diaphragm, but said her GP surgery "hadn't even heard of it".

Natika Halil, chief executive of the Family Planning Association, warns that there is a lot of misinformation around contraception.

While some women have concerns about taking hormones long-term, or taking a pill which means they do not have periods, Ms Halil says: "People shouldn't be scared. Contraceptive methods have really improved over the last 20 or 30 years."

National guidelines recommend that clinicians discuss all options including long-acting reversible contraceptives with their patients

Ms Halil says the pill can actually be beneficial for many women, for everything from their skin to their mood, although long-acting contraception is not the right option for everyone.

Alyssia, 26, had a largely good experience on the pill, but said that after 10 years she wanted to try something containing fewer hormones. However, the hormonal coil "didn't sit well" with her, and she now wants to have it removed.

'Misinformation'

Charlotte, 27, has polycystic ovary syndrome and went on the combined pill at the age of 15.

"I tried lots of different combined pills but felt they all turned me a bit crazy and made me emotionally unstable. I then went on the progesterone-only pill but I bled constantly.

"I was told the [hormonal] coil would be perfect. Unfortunately I bled the entire time I had this in as well," she told the BBC.

Dr Esti Acha, clinical lead for contraception and sexual health services for St Helens and Knowsley Hospitals, says the NHS guidelines are meant to ensure clinicians discuss all the options with their patients. And when they do, many women who come in for the pill decide to opt for something different.

Patients now ask her for LARCs - a big change from 20 years ago when women only knew to request the pill.

The pill represented a social revolution when it became available almost 60 years ago, but a new generation of women want more choice.

And despite different experiences, almost all of the women we spoke to said that was one change they had noticed - a shift in what was offered to them, from a very heavy focus on the pill to a much greater inclination to discuss the alternatives.