Why did more people die in depths of last winter?

- Published

Every year, more people die in the winter than the summer. Excess winter deaths, largely linked to the cold weather and flu, are expected.

But they were even higher this past winter in England and Wales than in previous years, and experts are concerned.

The government is launching an investigation. One academic in the field says it raises big questions about life expectancy, which in past years has been going up.

If you cannot view the life expectancy calculator, click to launch the interactive content, external.

So what might be going on?

The Office for National Statistics data for England shows a "statistically significant increase" in the death rate in the first quarter of 2018 and the highest for that period since 2009.

There were 1,187 deaths per 100,000 of population in England between January and March, up 5% on the same months of 2017.

Flu deaths surge during the winter

Crucially these figures are "age-standardised" which takes out the effect of ageing each year on the population as a whole. That way the figures can be directly compared with previous years.

The winter months this year included a difficult flu season for hospitals and some bitter cold snaps.

Those factors might have affected the death rate but the ONS notes that "influenza activity remained at medium levels throughout the whole of January and February 2018".

An expert in the field, Prof Danny Dorling, of University of Oxford, who has written extensively on health, housing and poverty, argues that declining living standards since the global financial crisis a decade ago have contributed to a higher winter death rate.

Cuts in social care in England and lower than average increases in NHS funding in recent years, he claims, could also have played a part.

There were increases in the first quarters of 2015 and 2017, as well as 2018.

This has fuelled speculation about whether a significant new trend is beginning to emerge.

Prof Dorling, together with Lucinda Hiam, honorary research fellow at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, in an article for the British Medical Journal , externalin March, urged the government to investigate the rising number of deaths.

Writing with another leading academic Martin McKee, in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in June, external, they state that the upward trajectory of life expectancy in England and Wales has stalled.

They note that after 2010 there is a "clear slowdown" in the rate of improvement in life expectancy, which has raised questions over whether there is a causal link with government austerity measures.

Ministers have denied that their policies have contributed to stalling life expectancy and rising mortality rates.

Poverty has been linked to higher death rates

The Department of Health and Social Care said in a statement: "The number of deaths can fluctuate each year but generally people are living longer. We are taking strong action on helping people live longer and healthier lives - cancer survival is at a record high while smoking rates are at an all-time low".

But there is increased interest in the issue at the highest levels of Whitehall.

The Department has called on Public Health England to carry out a review of mortality data "to better understand the trends of recent years".

The terms of reference will be announced soon and it is understood they will cover areas like excess winter deaths and deprivation.

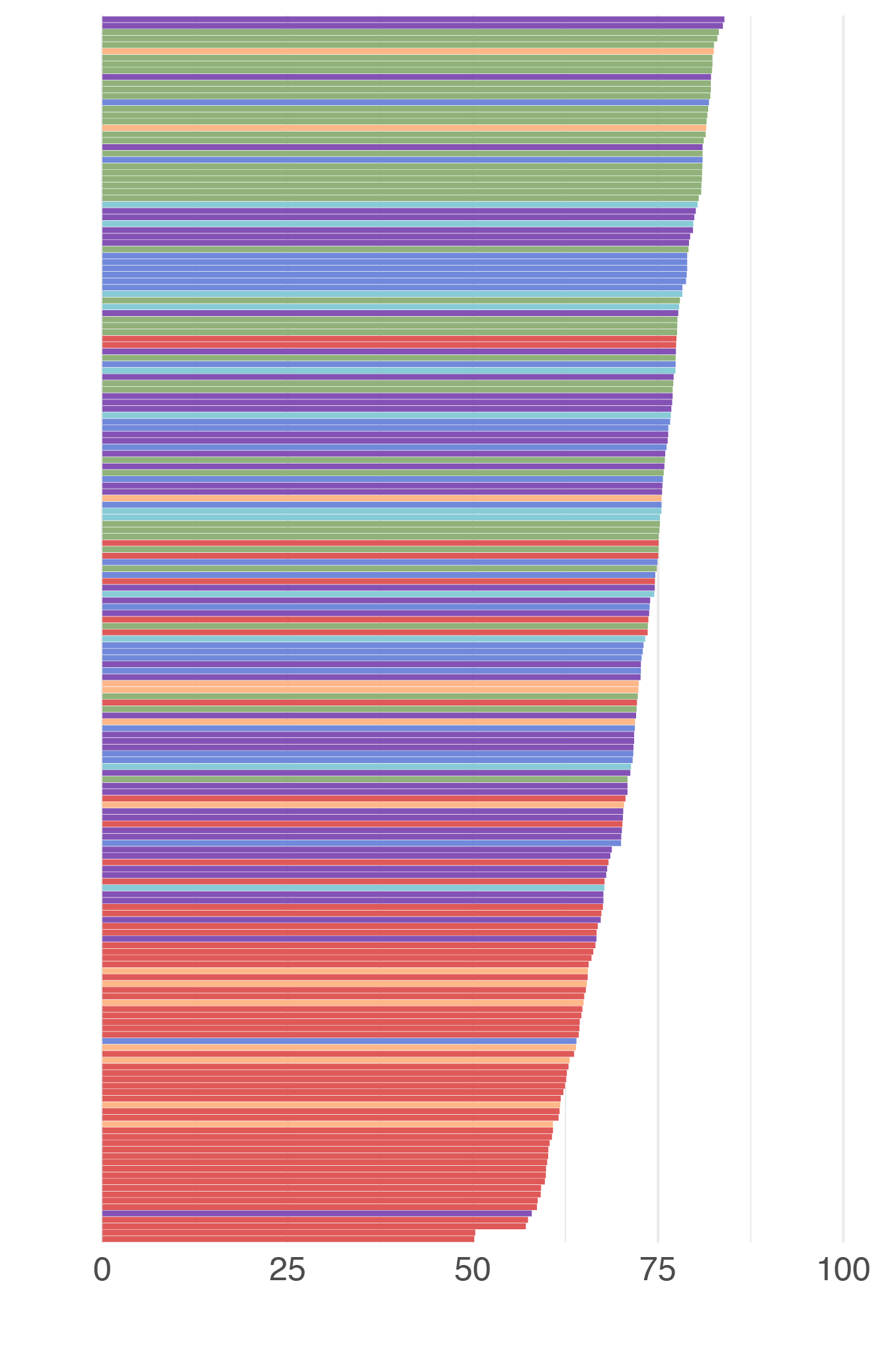

This comes at a time of increased scrutiny of a widening life expectancy gap between rich and poor.

Panorama's "Get Rich or Die Young" highlighted the fact that in Stockton-on-Tees, those living in the wealthier areas can expect to live as much as 18 years longer than those in the more deprived parts of the town.

In February, a report by a group of experts chaired by the former National Statistician Karen Dunnell said that a gap in life expectancy between the richest and poorest neighbourhoods in England had widened between 2001 and 2015.

According to the report, commissioned by Legal and General, a boy born in the most affluent areas in 2015 is expected to outlive one born in the least advantaged areas by nearly 8.5 years, up by more than a year since 2001.

The authors said the gap would persist if policies like social care cuts continued.

Prof Dorling argues that the recent ONS mortality data will inevitably influence the next official life expectancy projections and said: "We will see the first significant fall for men and women since the 1970s at least."

He has called for an urgent inquiry by the Commons Health and Social Care Committee allowing a full airing of expert evidence.

Some academics and politicians will disagree with his analysis, but there is no doubting that the debate is gathering momentum.

- Published18 July 2017