Hospital sepsis deaths 'jump by a third'

- Published

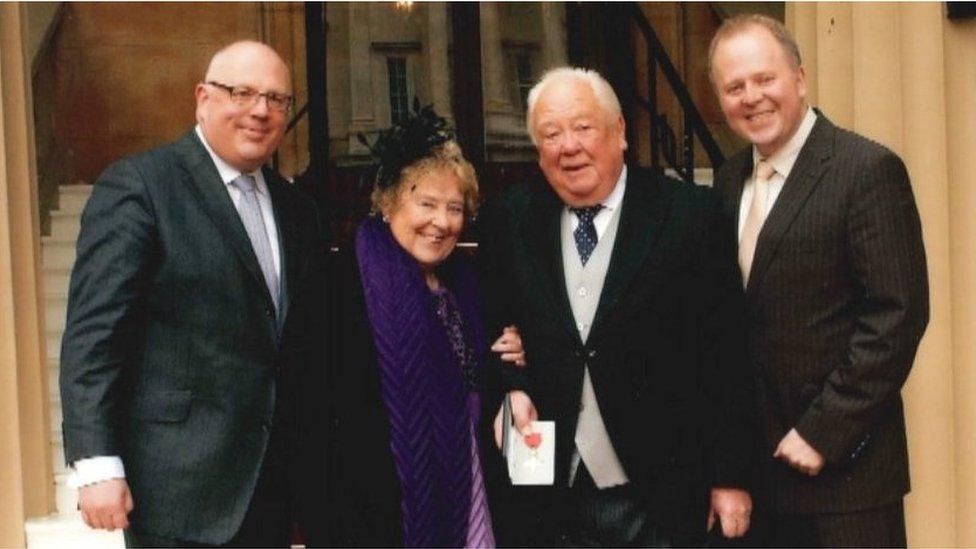

William Mead, from Cornwall, was 12 months old when he died in December 2014 after health professionals failed to recognise he had sepsis

Sepsis deaths recorded in England's hospitals have risen by more than a third in two years, according to data collected by a leading safety expert.

In the year ending April 2017, there were 15,722 deaths in hospital or within 30 days of discharge, where sepsis was the leading cause.

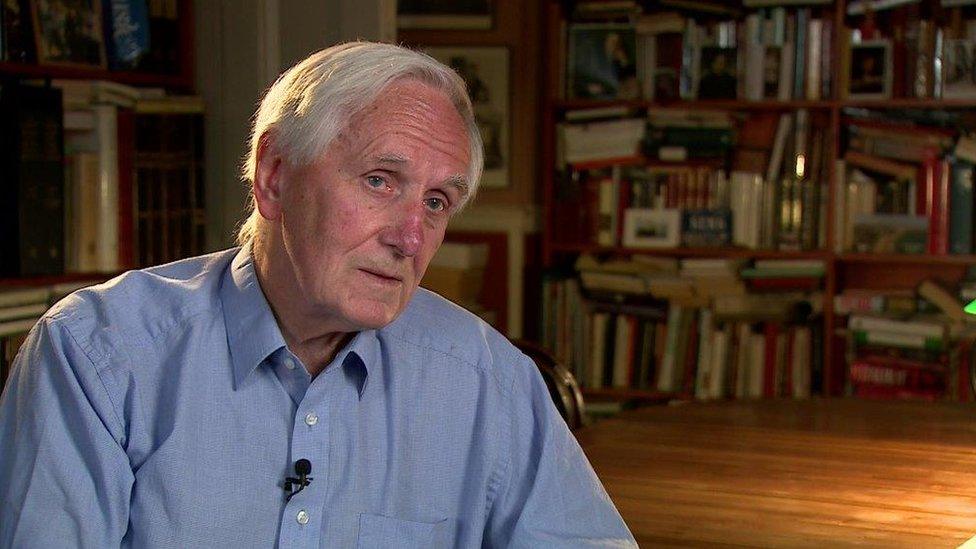

Prof Sir Brian Jarman believes staff shortages and overcrowding on wards are partly to blame.

NHS England said more conditions were being classed as sepsis than before.

A spokesperson added that efforts had also been made to improve diagnosis.

Sepsis is a rare but serious complication of an infection, which can lead to multiple organ failure if not treated quickly.

Melissa Mead, whose baby son William died of sepsis following a chest infection in December 2014, has been campaigning for greater awareness of the condition.

She said: "Whilst you have a lack of public awareness you are going to have people who are sitting at home, feeling poorly, and don't even realise that sepsis is even a thing.

"So we need to be looking at this from all angles. It's all very well having a world-class health system with surplus beds and surplus doctors, but if I'm sitting on my sofa at home feeling poorly and I don't know what sepsis is, I'm not going to get that care.

"It's making sure that every route is connected, that people have the information to make informed decisions about their onward care, and that when they access that care that they are listened to and their concerns are acted upon promptly."

Sir Brian, director of the Dr Foster research unit at Imperial College in London, hopes his data can be used to improve the survival chances of hospital patients who developed sepsis, via alerts that he sends to hospitals that are falling behind.

Prof Sir Brian Jarman

Speaking to the Today programme, he said: "Some of those hospitals with a lower death rate have got particular ways of reducing mortality from septicaemia, which the others we hope might learn from, and also we hope that by giving them this alert, within a month or two of the actual happening, they can actually get in there and do something quickly."

There has been a focus on screening for sepsis in the NHS in recent years, led by the UK Sepsis Trust, formed by a group of clinicians at the Good Hope Hospital near Birmingham.

Dr Ron Daniels, chief executive of the UK Sepsis Trust and an intensive care consultant, said sepsis was one of the most common causes of death in the UK, responsible for killing up to 44,000 people a year - in hospital and in the community.

He said that hospital records made it almost impossible to keep track of the true number of deaths.

Dr Daniels said: "It's very common that if someone dies of sepsis that it's coded or reported as simply being the underlying infection.

"So they might die of sepsis in an intensive care unit with multiple organ failure - but they're recorded as a death from pneumonia. We need to fix that problem before we can truly understand the scale of sepsis.

"The best way for us to do that is to develop a prospective data system like a registry that exists for other conditions, so that we can really get a national picture of what's going on."

He added: "The treatment for sepsis, if it's caught early enough, involves very basic interventions - looking for the source of the infection, giving antibiotics.

"For every hour we delay in giving antibiotics, the patient's risk of dying increases by a few per cent, so it's essential that we spot it early and deliver the basics of care quickly."

'Huge effort'

Sir Brian said: "The biggest thing that's important seems to be the number of staff - doctors per bed.

"One of the secondary important things is the overcrowding of hospitals. The level of overcrowding shouldn't be more than 85% [bed occupancy], and it's been going over 90% in recent years."

But Professor Bryan Williams, chair of medicine at University College London, said more cases of sepsis were actually being picked up.

"In reality what is happening is an increased awareness of sepsis and increased detection of sepsis and an actual reduction in mortality in hospital and in the first 30 days after discharge from sepsis."

He said it was important for the public to recognise that the NHS was taking sepsis "incredibly seriously".

"If you go to any hospital now it is treated as one of the priorities and death rates are falling," he said.

An NHS England spokesperson told the BBC: "Over the past three years there has been huge effort across the NHS to increase clinical recognition of, and recording of, sepsis.

"That improved method of recording means some cases previously recorded as simple infections are now classified as sepsis. So this data does not prove an increase in sepsis cases per se."

What is sepsis?

Sepsis is triggered by infections, but is actually a problem with our own immune system going into overdrive.

It starts with an infection that can come from anywhere - even a contaminated cut or insect bite.

'An infection took my legs, hands and nose'

Normally, your immune system kicks in to fight the infection and stop it spreading.

But if the infection manages to spread quickly round the body, then the immune system will launch a massive immune response to fight it.

This can also be a problem as the immune response can have catastrophic effects on the body, leading to septic shock, organ failure and even death.

Symptoms include:

slurred speech

extreme shivering or muscle pain

passing no urine in a day

severe breathlessness

"I feel like I might die"

skin mottled or discoloured

Symptoms in young children, external include:

looks mottled, bluish or pale

very lethargic or difficult to wake

abnormally cold to touch

breathing very fast

a rash that does not fade when you press it

a seizure or convulsion

Source: NHS Choices, external

- Published5 July 2018

- Published27 July 2018

- Published11 September 2017

- Published26 January 2016