Doctors’ mental health at tipping point

- Published

Sophie Spooner feared that her mental health problems would not be kept confidential if she asked for help

Patients rely on doctors to look after their mental health but is enough being done to help the doctors when they are the ones with problems? There are concerns that some medical professionals in England are unable to get the help they need.

In 2017, 26-year-old junior doctor Sophie Spooner suffered a panic attack while working on a paediatrics ward.

Twenty-four hours later, she had taken her own life.

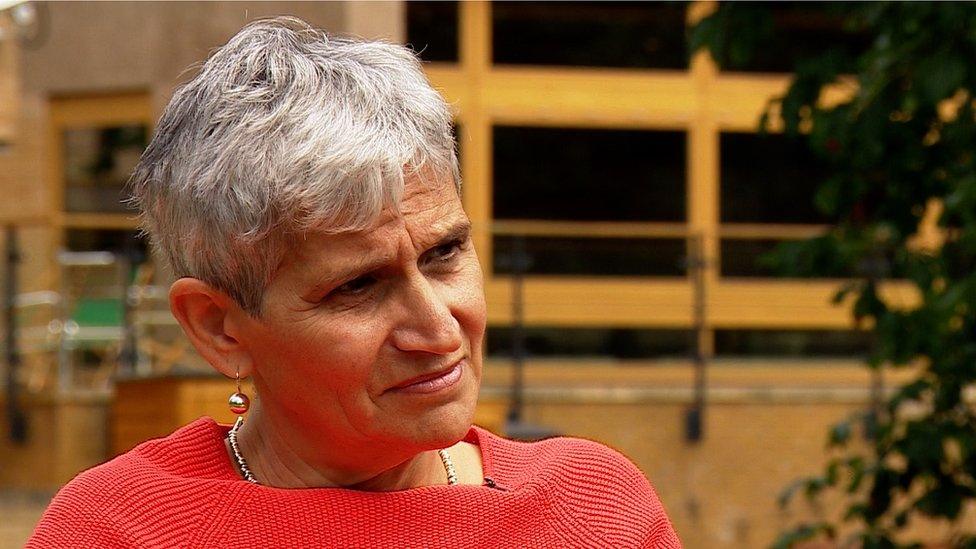

Her mother, Dr Laurel Spooner, believes her suicide was the result of depression which she had struggled with in the past. She had previously been diagnosed with bi-polar disorder.

"She was looking for a mental health service that would have understood her mental health problem in the context of being a doctor," Dr Laurel Spooner told the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme:

"If she could have seen somebody… and had the right medication, I expect she would still be here."

'Incredibly high risk'

Figures from the Office for National Statistics, covering England, showed that between 2011 and 2015, 430 health professionals took their own lives.

The NHS Practitioner Health Programme (PHP), is the only confidential service that offers doctors a range of assessments, treatment and case-management for all mental health problems.

But doctors can only self-refer to the PHP, without the need to tell their Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), if they work in London.

Others can access the service, but in telling their CCG they consequently lose their anonymity.

Dr Clare Gerada said doctors' mental health was the last taboo in the NHS

Its medical director, Dr Clare Gerada, says: "Doctors are at an incredibly high risk for mental illness," she said. "Female doctors have up to four times the risk of suicide in comparison to people in the [general] population."

In 10 years, the PHP has helped more than 5,000 doctors, of whom slightly over two-thirds were women. The average age has dropped from 51.6 years to 38.9.

But doctors can only self-refer if they work in London.

Other doctors can access the service, but they must do so via their local clinical commissioning group (CCG), thereby losing their anonymity.

If you have any mental health concerns

The Samaritans is available 24 hours a day and calls are completely confidential. You can email jo@samaritans.org or call 116 123.

HOPELineUK offer support, practical advice and information to young people considering suicide and advice if you are concerned about someone you know. Call 0800 068 41 41.

CALM aims to prevent male suicide in the UK and offers anonymous, confidential help. Call 0800 58 58 58 everyday between 17:00 BST and 00:00.

In texts to her mother before she died, Sophie Spooner said she feared she would be sent into hospital if she revealed her mental health issues and her colleagues would find out.

She also expressed her anger at not being able to access the PHP confidentially because she worked outside London.

'Last taboo'

Dr Gerada says the lack of confidentiality is a barrier and wants NHS England to extend the London approach to any doctor who needs support.

She believes acknowledging that doctors also have mental health problems is "the last taboo in the NHS".

Louise Freeman said she was desperate to keep working despite her mental health problems

Louise Freeman, a consultant in emergency medicine, says she left her job after she felt she could not access appropriate support for her depression.

"On the surface you might think 'Oh, doctors will get great mental health care because they'll know who to go to'.

"But actually we're kind of a hard-to-reach group. We can be quite worried about confidentiality," she said, adding that she believes doctors are afraid of coming forwards in case they lose their jobs.

"I was absolutely desperate to stay at work. I never wavered from that."

One of the biggest issues, according to Dr Gerada, is the effect on doctors of complaints from the public, which she says can "shatter their sense of self".

Sophie Spooner's death came two months after a complaint was made against her.

Nine months ago, consultant anaesthetist Richard Harding took his own life. A serious complaint had been made about him to the General Medical Council.

He was eventually cleared but the process took five months.

Kate Harding says the effects of complaints on doctors are long-lasting

His wife Kate Harding, a GP, says it brought back depression he had not had for years.

"Those five months just felt endless. Even after the complaint had been shelved, he was the type of person - afterwards - who questioned his decisions a lot more.

"The effects are more long-lasting than you'd expect. I don't think it occurred to him to seek help."

Anna Rowland, assistant director of the GMC's fitness-to-practise department, said the organisation had made major reforms to its processes, with an emphasis on mental health, to ensure vulnerable doctors were identified and supported.

She said: "We're committed to continuing this work, and we're also keen to influence the way wellbeing is approached by other healthcare leaders through independent research... health organisations must come together to tackle these important issues."

NHS England said in a statement: "We launched the NHS GP Health service in 2017, a world-first, nationally funded confidential service which specialises in supporting GPs and trainee GPs experiencing mental ill health and which has already helped more than 1,500 GPs.

"NHS Trusts and clinical commissioning groups may offer additional support for professionals in their area, for example CCGs in London have commissioned the NHS practitioner health programme for their staff."

But Dr Laurel Spooner says more support is needed.

"If we don't learn lessons from this, these deaths will go on happening," she says.

Watch the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme on weekdays between 09:00 and 11:00 BST on BBC Two and the BBC News Channel in the UK and on iPlayer afterwards.

- Published19 April 2018