'I gave birth, and got Hepatitis C'

- Published

Jackie describes the effects of having hepatitis C as "trauma after trauma"

When Jackie Britton was given a blood transfusion after childbirth, she thought it was saving her life. But the infected blood could have killed her. There are thought to be thousands like her. They often feel overlooked in the wider NHS contaminated blood scandal.

"There are still people dying, not knowing they are infected," Jackie Britton, from Portsmouth, tells the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme.

She gave birth in 1983.

Her baby daughter was fine but when Jackie started haemorrhaging she needed a blood transfusion.

It would be another 29 years before she realised that that blood had been contaminated with hepatitis C, for which there was no blood screening at the time.

The virus went undetected for years, slowly damaging Jackie's liver.

As she puts it: "The four units of blood that had saved my life was killing me."

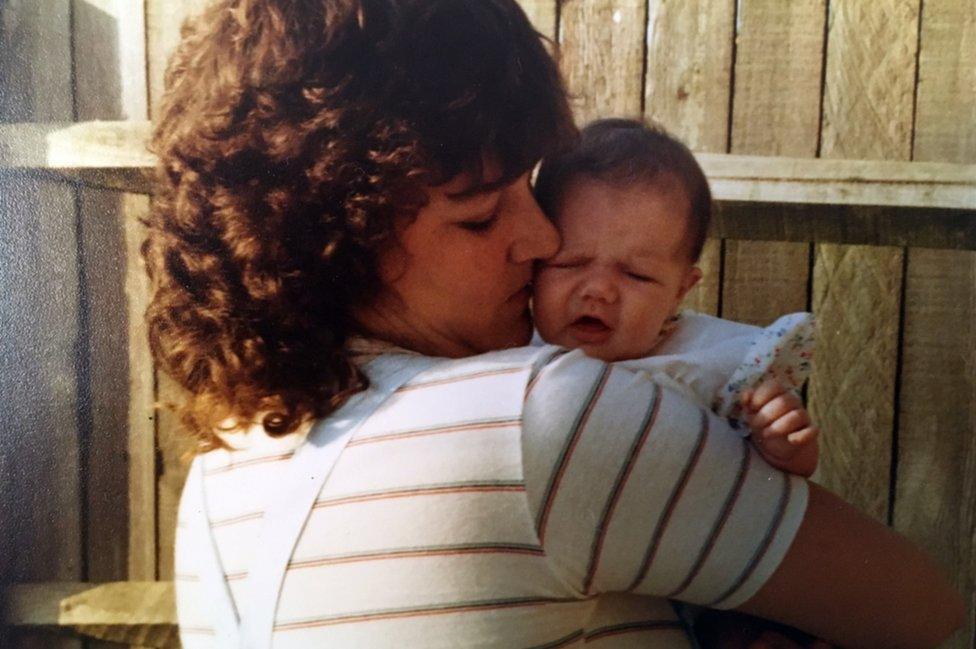

Jackie had her daughter in 1983

Jackie started noticing something might be wrong only in her 50s, when she was experiencing "absolute fatigue".

"I would feel physically sick. I would start retching just stood up trying to cook a meal, because of the effort and the energy it was taking out of me.

"Hep C is just trauma after trauma."

A new generation of drugs means Jackie has now cleared the virus itself from her body - but the damage has already been done.

She has cirrhosis of the liver and needs checks every six month to make sure it has not led to cancer or liver disease.

'Treatment disaster'

The contaminated blood scandal of the 1970s and 1980s is often called the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Almost 5,000 people with the blood disorder haemophilia were given a treatment contaminated with hepatitis and in many cases HIV.

Then there is a second group of people who like Jackie received a blood transfusion after childbirth or an operation.

There are no solid figures available on exactly how many transfusion patients were infected before 1992.

But estimates range from about 5,000 - the same number of people with haemophilia affected - to up to 28,000, the figure suggested by a Department of Health analysis of the scandal.

It is thought there will still be some people living today with hepatitis C, contracted by blood transfusion, who have not yet been diagnosed.

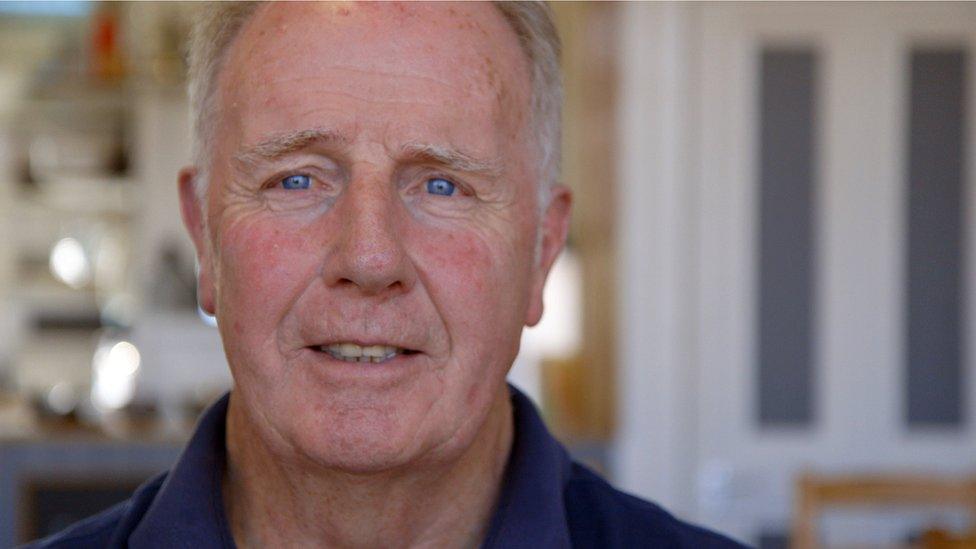

Bob Leary was infected following an operation for a burst intestine

For Bob Leary, now 72, it all started in 1986 with a burst intestine.

Admitted to hospital and given a transfusion, he didn't think much more of it until he had a blood test four years later.

He was told he had hepatitis C and could expect to live for another 10 to 15 years.

"As you can imagine, it was a very severe shock," he says.

By 2012, Bob's liver had started to fail. He became jaundiced and lost weight dramatically.

The following year, having been told he had just weeks left to live, a liver transplant saved his life.

He will be on medication until he dies.

"I don't want to get into the blame culture, I could be bitter all my life," he says, "but we need to make sure nothing like this happens again."

His hope is that a public inquiry into the contaminated blood scandal, set to begin on Monday, will provide some answers.

It comes after years of campaigning from victims and their families.

Key issues include:

whether the government could have moved faster and introduced blood screening for hepatitis C before 1991

whether officials knew about the risks of contamination but decided not to tell the public

whether enough was done to find and test patients who were given a transfusion before 1992

'She loved living'

For Jackie, it is about far more than her own health.

Last year, her friend and fellow campaigner Sally Vickers died from cancer caused by the hepatitis C she contracted in 1982 following an operation.

"She loved living. I mean she fought and fought," says Sally's husband, Alan.

He remembers the moment she was given less than a month to live.

"The specialist came down and said, 'I'm sorry, it's not only severe cancer in your liver but it has spread to your lungs.

"We simply wanted to come home so that she could be with me."

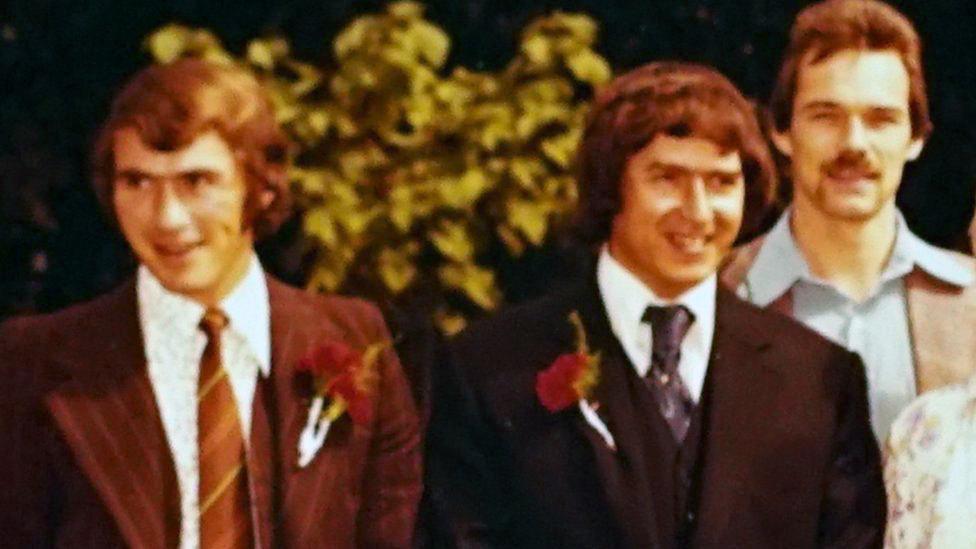

Sally Vickers contracted hepatitis C from contaminated blood

The anger Alan and Sally felt, however, was not directed at doctors, or the NHS, but at the people responsible for the whole blood donation system at the time in the Department of Health.

"I want somebody held accountable for it," Alan says.

"Somebody has got to be accountable for this."

The Cabinet Office said in a statement: "The Infected Blood Inquiry is a priority for the government.

"It is extremely important that all those that have suffered so terribly can get the answers they have spent decades waiting for and lessons can be learnt so that a tragedy of this scale can never happen again.

"Government is committed to providing the inquiry with all the support it needs."

Watch the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme on weekdays between 09:00 and 11:00 BST on BBC Two and the BBC News channel in the UK and on iPlayer afterwards.

- Published30 April 2018

- Published11 April 2017