What do astronauts and one in five women have in common?

- Published

For thousands of years, nutrition has been a driving factor behind the success or failure of human exploration. This is particularly true in the case of space flight.

It is vital to prevent the astronauts from becoming malnourished during missions, which often last months.

But modern space nutrition goes further than that. It aims to maximise the crew's performance while reducing the damaging effects of space flight and protecting against long-term health risks like cancer and heart disease.

It may seem excessive to put so much effort into the nutrition of the handful of people who venture into space.

But as with most space research, any breakthroughs have clear implications for those staying behind on Earth.

Poor eyesight and fertility: what's the link?

Some astronauts are returning from space with eye problems, external. This includes effects on the back of the eye such as "cotton wool spots" - fluffy white spots on the retina - and swelling of the optic nerve.

In other words: some astronauts have left the planet with perfect vision, but came home needing glasses.

The effects of microgravity on the circulatory system have previously been held to blame, including shifts in body fluid and increased pressure on the brain.

The International Space Station

But these theories don't explain why only 30-40% of astronauts develop eye problems. Could there be another reason?

Our theory is that genetic differences could affect how their blood vessels function.

When combined with a triggering factor during space flight - such as shifts in body fluid - this leads to leakier blood vessels in or around the eye. This causes pressure to build up, leading to eye problems.

The affected crew members were found to have significantly higher concentrations of a chemical called homocysteine, not only during and after the flight, but before as well.

Homocysteine is part of a biochemical pathway occurring in virtually every cell in the body, and requires many different types of B vitamin to function.

Astronauts reporting eye problems may need a bigger dose of these B vitamins than others, because of their genetic makeup.

Astronaut Karen Nyberg taking an eye exam

An intriguing element of this research is that women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) also tend to have higher than average concentrations of homocysteine and circulatory issues similar to those detected in the (male) astronauts with eye problems.

PCOS affects how women's ovaries work. It is the leading cause of fertility problems and is thought to affect up to 20% of all women.

This condition isn't well understood and at present there is no cure. But it is possible that, as they share a similar blood chemistry, women with PCOS may also benefit from additional B vitamins.

There is no definitive evidence yet, but studies are under way, external by Nasa and physicians at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota to investigate the potential link.

This research has the potential not only to solve one of the key health risks of space missions, but also to better understand a syndrome that affects millions of people.

Studying space by staying in bed

Astronaut nutrition studies help us understand how humans could adapt to longer space flight - and how we can improve our lives on Earth

Studies in space usually have to be done with limited resources and face the challenges of weightlessness, or "microgravity"

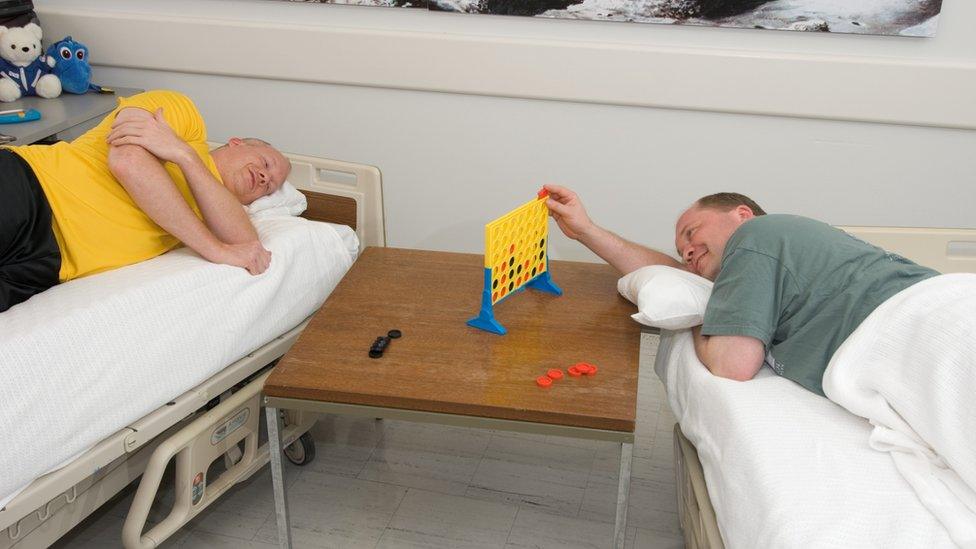

Earthbound studies are sometimes used with healthy subjects confined to bed, external for weeks or months in a head-down tilt position

This recreates the effects of microgravity and allows monitoring of bone and muscle loss and other changes

Keeping busy during a bed rest study

Lack of sunlight

Our skin creates vitamin D when it is exposed to sunlight. It's needed to keep bones, teeth and muscles healthy.

Astronauts don't get enough vitamin D during space missions, as they are protected from sunlight exposure, external and are unable to get enough from their food supply.

In order to study the effects of sunlight deficiency, we worked with crews wintering at the McMurdo scientific research centre in Antarctica, where the sun doesn't come up for six months at a time.

There we conducted experiments to see whether taking vitamin D supplements would be a sufficient replacement for sunlight.

The initial study, external found small supplements did help to increase vitamin D levels, but that a bigger dose didn't give much extra benefit.

When the US National Academy of Medicine increased the vitamin D requirements for North Americans, external, this study - and many others - helped them make that decision.

We also found the response to supplements was affected by body weight, or Body Mass Index (BMI). The higher the BMI, the less effective the vitamin D supplements.

This makes sense, because fat grabs the vitamin D and prevents it staying in the blood.

In our second study, external, we looked at immune system function and stress, which are concerns for both astronauts and crews wintering over in Antarctica.

We found these factors seemed to interact with each other. People who showed chemical signs of stress and had low levels of vitamin D were more likely to find it difficult to suppress viruses such as cold sores that were lying dormant in their system.

Most vitamin D studies have to contend with their subjects having some exposure to the sun, potentially confusing the results. These Antarctic studies allowed us to strip out that factor and suggested that the new vitamin D recommendations for the wider population were reasonable, with little extra benefit from a higher dose.

The secret to strong bones

Bone loss has long been one of the biggest concerns for space travellers. Astronauts tend to lose their bone mass at roughly 1% per month, the amount that osteoporosis sufferers lose in a year.

The loss occurs because the body doesn't place gravity on the bones, and "decides" that you can get by with a smaller skeleton. On average it takes years for bone mass to recover after a mission.

After years of trial and error, several specific diet changes have been found to have a positive effect on bone health, external.

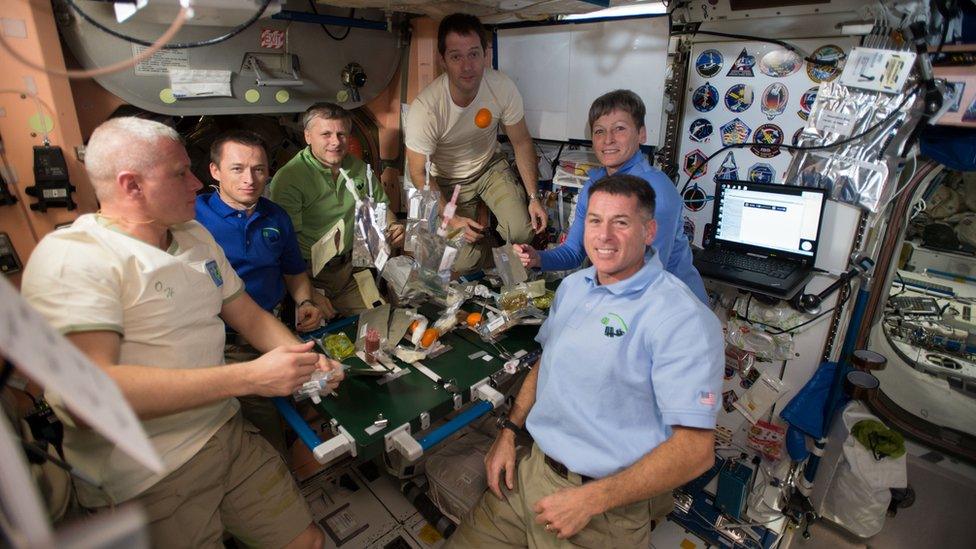

Astronauts on expedition 50 at meal time

Astronauts who had higher intake of fish like salmon and mackerel lost less bone while in orbit. We also found that diets with more fruits and vegetables were beneficial to bone strength.

Conversely, large intakes of iron and sodium served to speed up bone loss.

Subsequent evidence showed that astronauts who ate well, had enough vitamin D, and exercised hard didn't suffer any bone loss during a six-month space mission.

This was the first time in 50 years of human space flight that crew members had been able to maintain their bone density with nothing but diet and exercise.

These findings also have direct implications for literally everyone on Earth, where the same diet changes could help keep our bones healthy.

The challenges of eating carrots in space

Paving the way

As we approach the sixth decade of human space travel, we stand at the beginning of humanity's forays into space. The accompanying health risks are significant, and nutrition could provide the key for longer, more distant missions to other planets such as Mars.

We need to dare to use and expand our 21st Century knowledge of nutrition, uniting medical and scientific teams to enable future exploration, while simultaneously benefiting humanity.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Dr Scott M Smith, external and Dr Sara R Zwart lead the Nutritional Biochemistry Laboratory at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Dr Smith is speaking at the October Wellcome/WHO conference "Transforming Nutrition Science for Better Health", external.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie