Food allergies: What a severe reaction feels like

- Published

A salad nearly killed my brother.

It was the mid-1990s. The incident involved a self-service counter and one bowl that contained hidden nuts.

Adam was 10 years old. I was older, but still at school. I remember the nurse coming into my classroom to say he had been taken to hospital and I should make my own way home. My dad phoned me when I got there, trying to reassure me that everyone would be home soon. But knowing he must have raced back early from work, I felt uneasy.

What I didn't know was that Adam was in a critical condition in an A&E bed. My parents had always avoided giving him nuts, because I had a severe allergy and we suspected he might too. This accidental consumption was the first proof. His body had gone into anaphylactic shock - a severe and potentially life-threatening reaction to an allergen.

Luckily, due to fast treatment, he pulled through. Afterwards, he got his first Epipen - a self-administering adrenalin injection - to give him a better first line of defence. My mum also complained to the supermarket and they changed their salad-bar policy, labelling the contents of each bowl and tethering the cartons to reduce risks of cross-contamination.

Over the years, we have both got used to having the occasional "run in" with a nut. You do all that you can to be careful. You check the menu; you quiz the waiters; you scan the small print in the supermarket; you ask questions when anyone offers you a biscuit. You essentially do a risk assessment every time you eat, and mostly without realising you're doing it.

Yet sometimes you slip up, or the restaurant does. Maybe a waiter forgets to pass your message on. Or perhaps you take a carefree bite into a Mexican taco because who puts peanuts in tacos? (Answer: an experimental London chef.)

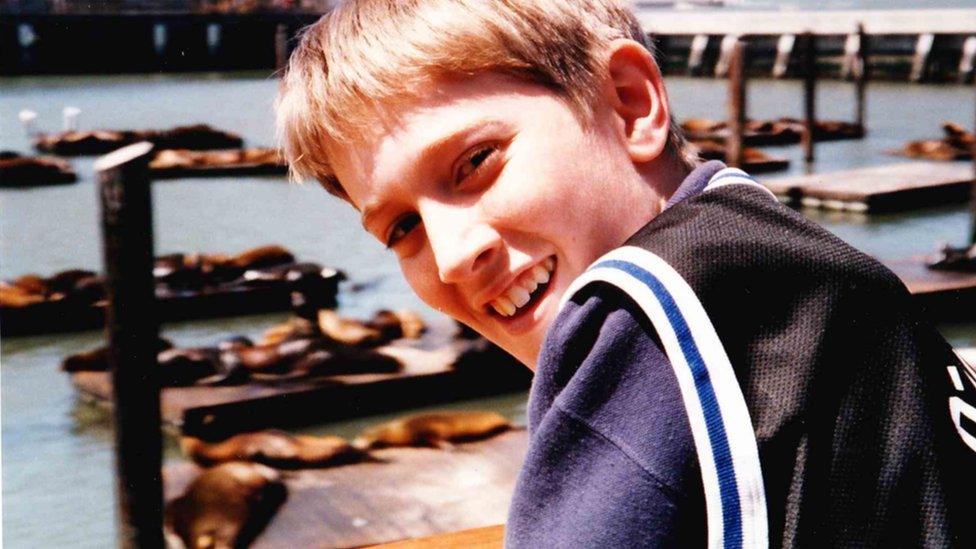

Adam at the age when he had his first anaphylactic shock

Cases of nut allergy among children increased significantly during the 1990s, according to the UK-based support group the Anaphylaxis Campaign.

Researchers are trying to work out why this is happening, and what can be done, including experimenting with weaning and desensitisation trials.

In the meantime, those of us who belong to this unfortunate club have been adapting to survive.

And to avoid overhyping, it is worth pointing out that deaths are still rare. US researchers have said people are more likely to die in an accident or be murdered. Which is reassuring, I suppose.

The mother's take

Lucy Patterson, who works for a charity near Cardiff, has a four-year-old son who has a whole host of severe allergies.

The first sign of Jack's problem came when he was five months old and cow's milk in his porridge sent him into anaphylactic shock. Tests afterwards showed he was allergic to milk, eggs and nuts.

"When we buy food, we double and triple check the labels. Even if we bought the product before," she says. Jack also carries two Epipens at all times.

As a family, they have decided not to eat out or travel abroad while he is young, but she hopes he will be able to do both in the future. "I don't want to bring Jack up in fear. My job is to educate and protect him as much as I can, and that's easy when he's four.

"He is likely to eat out when he's older, so my job then is to ensure he asks the right questions, always carries his Epipens and that the friends he is with know the situation fully."

Jack wears a badge to alert others to his severe allergies

What it feels like

When I read the recent news that Natasha Ednan-Laperouse died after eating a Pret baguette, I knew the panic she must have gone through. That moment when you first reach for an antihistamine tablet, or an Epipen, and are unsure if your body can bring the situation back under control.

I have had chefs and waiters refuse to believe me when I say I am having an allergic reaction. "There were no nuts in that dish," they insist flatly.

But it is not debatable as far as I am concerned. When there are nuts in a dish - particularly peanuts - I know as soon as the fork touches my tongue. Within seconds, my whole mouth and throat are overwhelmed by an intensely unpleasant sensation that is hard to describe. It is not a taste, more like an anti-taste, which sucks all other flavours out of my mouth, leaving a dry burn.

There are plenty of hazards in a US cereal aisle

Not all reactions are the same, though. Aside from the more serious effects of anaphylaxis, some people wheeze, others get stomach cramps. According to the British Medical Journal, one of the symptoms is a "sense of impending doom", which I find darkly hilarious but also true. The varying degrees of severity mean that some people are more willing to take risks than others.

I remember a waiter at a hotel-restaurant once refusing to accept there were any nuts in what he had just served me. Fearing my throat might start to close, I wasn't in a position to continue arguing, but I knew there was no doubt.

Once I had recovered, the waiter and the chef came to my room to apologise; they admitted there were peanuts in an appetiser, there had been a miscommunication. The hotel owners also visited me the next day, saying this had never happened before and they were going to do all they could to ensure it didn't happen again, starting by briefing all staff.

Obviously I would have preferred not to have been the guinea pig, but this felt like progress. I had been listened to and taken seriously - eventually.

The chef's take

Amanda Freitag is a judge on Food Network's Chopped

US chef and television host Amanda Freitag has a serious hazelnut allergy and ran a hazelnut-free kitchen when she was at the helm of New York City's Empire Diner.

"As soon as I started to talk about my allergy, some of my other colleagues revealed they have food allergies as well," she says. "It's not something a chef always wants to discuss because we don't want to be limited in what we eat or cook. But I find it a welcome challenge to make a dish without the allergen. I like working to make the dish just as good or better."

Her advice to other chefs would be to take all allergies and food sensitivities very seriously.

"Do consistent menu training with all your staff - kitchen and front of the house - so that they are aware of all the ingredients in every dish and, if they are uncertain, to always come to the kitchen and ask to confirm," she says. "Having menu descriptions written and constantly updated for the staff to reference is essential."

What else companies can do to help

Pret A Manger - a major UK sandwich chain - has been under scrutiny for its approach to labelling after two deaths linked to its products, first Natasha and also in a dairy-allergy case.

In 2015, I accidentally ate nuts in a Pret sandwich and I emailed them to ask if they would consider labels on the products. They told me this would be "impossible" and they only sought to "provide a description of the flavours one may expect in a sandwich". Natasha died the following year.

After an inquest, they have now agreed to bring in labels.

On the other end of the scale, I remember one major supermarket going through a phase of labelling everything with "May contain nuts" - even ham and orange squash. That was not particularly helpful.

However, other companies have been praised for their approach. In the UK, many nut-allergy sufferers are fond of Welsh chocolate company Kinnerton, which prides itself on going to "extraordinary lengths" to make their produce safe. They even created two factories - one for nut produce, one for nut-free produce. If you want to set foot in the latter, you have to sign a document saying you have not eaten nuts that day or brought any with you.

Airlines - which traditionally serve peanuts as on-board snacks - have also been under pressure to adapt to the times.

It was in mid-air that my brother had his second-most serious anaphylactic shock. He now picks his flights based on their nut policy. British Airways still serves some nuts, so they are on the "no" list. Whereas EasyJet will agree to stop serving all nuts if you let them know, and this reassures him.

In August, US company Southwest Airlines stopped serving peanuts on all its flights, but signalled the move with a particularly melodramatic goodbye. "Peanuts forever will be part of Southwest's history and DNA," it wrote in a press release.

The doctor's take

"The allergy community is very bruised by recent reports of fatal food-induced reactions," says Professor George Du Toit, a specialist in paediatric allergy at the Evelina London Children's Hospital, Guy's and St Thomas' Trust.

"It is extremely distressing when you see legal cases [such as the Pret A Manger case] playing out in the media. The reports typically arise long after the event, with delayed and mixed messages associated. This is all very frightening for allergic patients and their families," he says.

He said a shortage of Epipens had compounded the fears.

"Hopefully these tragic reports will lead to an increased understanding of food allergies and improved government support for increased provision of services to diagnose and support patients. The legislation around food allergen labelling is also in need of urgent review."

In The Times, writer Dominic Lawson responded to the Pret scandal, external by saying people with severe allergies should never eat outside their house.

Yet seeing as we are more likely to die in a car accident, should we stay in the house because of that, too? When driving, we all take reasonable precautions, like wearing a seatbelt and observing traffic lights; we also put a certain amount of confidence in other drivers and the company that made our cars. That's what I do when I eat out.

Having a serious allergy is mostly just annoying. Believe me, I'd really rather not ask the questions or cause a fuss. I can appreciate it can be annoying for chefs and companies too. But it looks like we are all stuck with the problem, at least for now, and more co-operation and understanding could save lives.

- Published25 September 2018

- Published1 October 2018

- Published29 January 2018