Reality Check: What are the targets for mental health?

- Published

The government is consulting on introducing the same sort of targets for people to be seen by a mental health specialist as are currently in place for waiting times in accident and emergency units and for cancer treatment, Health Secretary Matt Hancock has told BBC News - but there are already some targets in place.

Psychosis

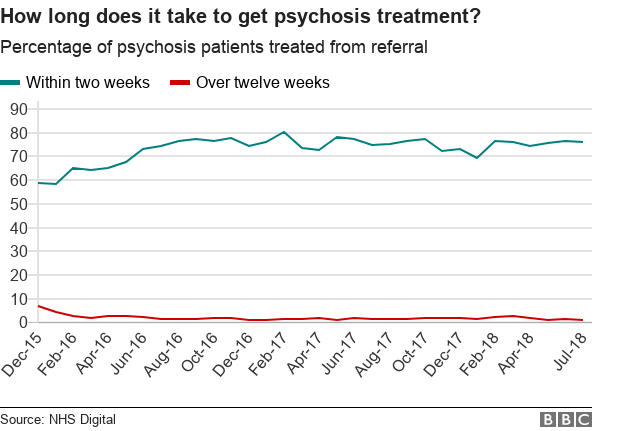

The percentage of patients, external starting treatment for psychosis within two weeks of referral increased from 59% in December 2015 to a peak of 80% in February 2017 before dropping to 76% in July this year. And the target, 50%, will be raised to 60% in the next few years.

The percentage of those waiting for early intervention in psychosis for more than 12 weeks fell from 7% to 1% during the same period.

Children's mental health services

The government set a target in 2016, external that 70,000 additional children and young people each year should receive treatment for mental health until 2020-21.

This would increase the NHS-funded treatment rate of the children and young people in England with diagnosable mental health issues from 25% to 35%.

Recently, the NHS released a "one-off" data collection that put the rate at 30.5% - on track to meet the target.

But the National Audit Office has raised concerns, external about "data weakness" around these figures.

"We have further concerns about the equivalence of the 70,000 target to a 10% increase in access rates," the NAO report says.

"It does not yet have consistent and reliable data available on the number and proportion of young people accessing treatment each year, so NHS England cannot be confident about the growth rates in access."

Equally, the target is based on assumed prevalence of mental health problems in young people.

So if more of them have mental health problems than previously assumed, the number required to meet the target will have to rise proportionately.

Children with eating disorders

Another target says children and young people with eating disorders in England should receive treatment within a week of referral, external, in urgent cases.

This is also a relatively new target, starting in the first quarter of 2016-17, when 65% of children were seen within a week. In the latest quarter, this increased to 75%.

Less urgent "routine" cases should be seen within four weeks. There have been improvements here too - from 65% to 81% since the statistics were published.

Access to talking therapy

For those referred for psychological therapies, there is a standard, external that 75% should start treatment within six weeks of referral and 95% should start treatment within 18 weeks of referral.

This kind of treatment, for patients with disorders such as anxiety and depression, can range from cognitive behaviour therapy to online self-help courses.

In 2016-17, there were 866,527 referrals to this kind of treatment who had their first appointment within six weeks, 88% of all referrals.

The second target was also met - with 98.2% seen within 18 weeks.

This is an improvement from the previous year - when the target was introduced - when 81.3% waited less than six weeks and 96.2% waited less than 18 weeks.

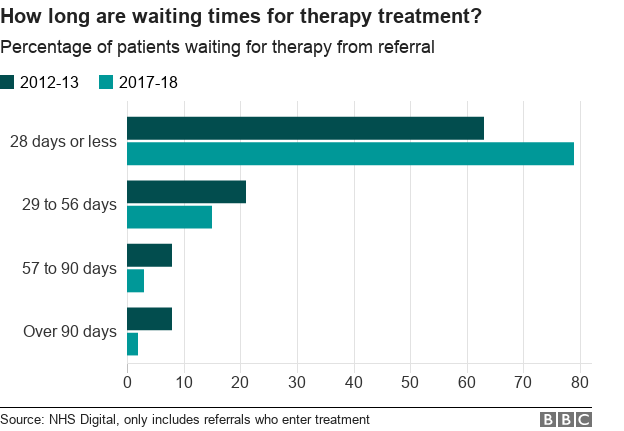

Before these targets were established, data was given on how many received treatment within 56 days of referral.

In 2012-13, 84% were receiving treatment in that time period. In 2016-17, this had increased to 94%.

Funding

As part of "parity of esteem" between mental and physical health, clinical commissioning groups - the organisations that deal with hospital and community health in a local area - are required to increase mental health spending relative to the amount their budgets increase.

And there has been an increase in CCGs meeting this target - from 81% in 2015-16, when it was set, to 90% in 2017-18.

On average, CCGs are spending 13.7% of their overall budgets on mental health.

- Published13 June 2019