Let down by 'agonising' end-of-life care

- Published

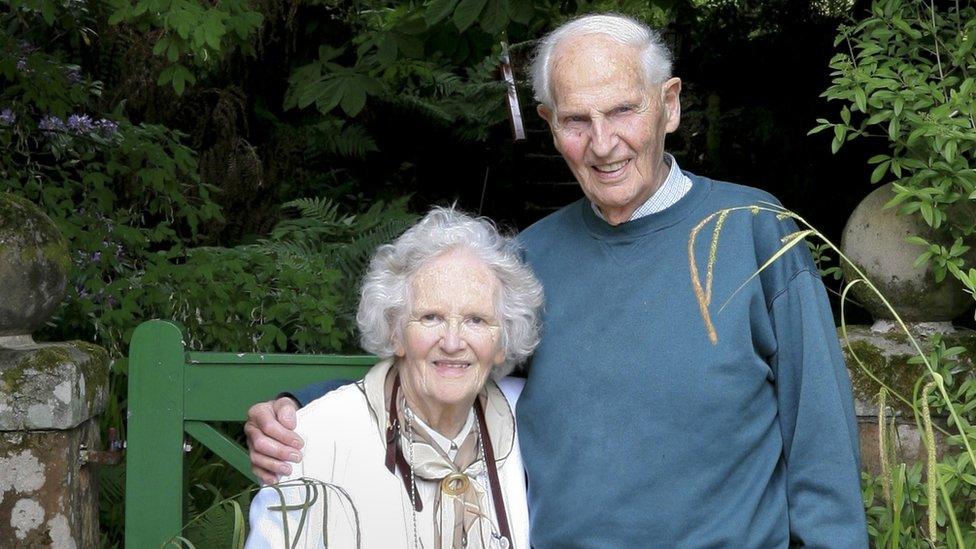

Anne Winternitz and her husband Fred

Staff shortages and inadequate training mean that end-of-life care for elderly people is often unacceptable, a leading expert has warned.

Andrea Sutcliffe, of the Care Quality Commission, told the BBC every nursing home needed to be capable of supporting people at the end of their lives.

Her call follows complaints from some relatives that their loved ones are dying distressing and painful deaths.

There is no legal requirement for end-of-life training for care home staff.

There are voluntary frameworks that care homes can sign up to, but many do not do so.

Ms Sutcliffe, who is the chief inspector of adult social care for the regulatory commission said: "Nursing homes are where we see the greatest struggles in adult social care, largely because of the difficulty in recruiting and retaining skilled nursing staff.

"It's not acceptable that we cannot support people at the end of their life in the way that we want to. Some people can do it but it's not happening everywhere and we need to get that sorted."

End-of-life care

Relatives of two women who died in a central London nursing home run by Bupa told the BBC that even though it advertised end-of-life care, staff at the home were inexperienced and unable to offer timely relief to dying residents.

Bupa says staff have had additional training since the deaths in 2017.

The Kensington Care Home, where private care fees can be more than £100,000 a year, promises to provide palliative care that meets residents' "physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs".

But relatives of two elderly women who died there have said that the experience was harrowing.

Anne's story

Ingrid Parry's mother Anne Winternitz died in the Kensington Care Home in May 2017 at the age of 92.

Mrs Parry said that in April, her mother, who had become critically ill, was put in an ambulance to go to hospital.

Having insisted on her mother being discharged back to the nursing home as she preferred to die in her own room, Mrs Parry said she urged the nursing staff to arrange all medicines necessary for end-of-life care to be ready there.

Anne with her granddaughter

She said: "It was clear that the home didn't have anyone trained to use a syringe driver, and it was clear that my mother's GP expected them to have [that] ability."

A syringe driver is a small pump used to deliver medicine and is often used as a way of offering pain relief to patients at the end of life.

Anne died a few weeks later, but staff initially believed she had a chest infection.

Mrs Parry said: "None of the staff there, apart from one wonderful carer, recognised the signs of dying.

"I'm frantically trying to get someone to recognise that she's dying and the frustration of having all the end-of-life drugs that would have eased her pain and agitation and fear down the corridor and not getting anyone prepared to administer them.

"At one point I got the nurse to come and sit with me to watch my mother and she asked me what I saw.

"I said I saw the most cruel thing, that no-one should ever go through. You should not have to die that way.

"It's absolutely awful and will be with me forever."

Barbara's story

Lindy Erskine's mother Barbara Webber died at the same care home in December 2017 at the age of 106.

Mrs Webber's GP had left sedatives and painkillers at the home more than three months previously, but her daughter said staff failed to administer them in good time.

She said: "Everything was ready. There was a wait, four, five-and-a-half hours. It doesn't sound very long but it's very, very long when you have a very elderly person in pain and distress.

"I found that [the nurse] was ringing up the GP because she didn't know the correct dosage and she didn't know the manner of delivery. She needed medical advice. The GP was very busy and there was no answer.

"She didn't have the medical confidence to know what to do."

Mrs Erskine said that nurses working with elderly people should have extra training in palliative care by law.

The home's most recent CQC inspection report, external, from August 2017, found that the service "requires improvement", and criticises its "end-of-life medicines administration and a lack of appropriate training in this area for nursing staff".

Ms Sutcliffe said: "Every single nursing home which is particularly supporting older people and people who are living with dementia should be capable of supporting people at the end of life. They absolutely need to make sure they've got sufficient staff, that they've trained them properly, and that they understand the needs of their residents so that they can meet them."

Vivienne Birch, director of quality for Bupa Care Services, said: "We don't recognise that our team lacked confidence addressing these residents' care needs and our team has completed more, regular training since last year.

"Staff training is carried out on a regular basis so that our team have the skills to care for our residents.

"All of the team have done additional training since the CQC inspection last year, including palliative care training in April."

When asked whether all homes had a member of staff trained in the use of a syringe driver, Bupa replied: "Syringe-driver training is available to all registered nurses in our care homes who provide palliative care to our residents."

- Published19 October 2018

- Published14 September 2018