'I was aged 24, and dead for five minutes'

- Published

Lora says doctors told her she was dead for five minutes

More than 80,000 young people in the UK could be living with undiagnosed heart conditions, the British Heart Foundation has warned. If undetected, the consequences can be fatal.

"My lips had started going blue, I'd stopped breathing, my heart had stopped," Lora D'Alesio tells the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme, recounting how she went into cardiac arrest.

"I was lifeless and dead for five minutes, and I understand the doctors were working tirelessly to bring me back to life."

Three years ago the 27 year-old veterinary nurse collapsed at home, having returned from work.

"I said I felt faint, and when [my housemate] turned round to check on me, I was on the floor. She thought I was messing around at first."

Lora woke up in hospital confused, after three days in a coma

Like many young people in her situation, Lora was not aware at the time that she had a serious heart condition.

Her life was saved by the emergency services, and after three days in a coma she woke up in hospital.

"I was crying because I was so confused," she explains.

Lora was diagnosed with something called Long QT syndrome - an inherited problem affecting the heart's rhythm, where the heart muscle takes longer to recharge between beats.

"At my age, I thought, 'No way.' I was 24 for goodness sake.

"You think of older people dropping dead because of frail hearts or heart disease, but not young people."

Preventing deaths

New research from the British Heart Foundation estimates 83,000 people aged 15 to 25 may have a faulty gene that puts them at an unusually high risk of developing heart disease or dying suddenly at a young age.

Many of those people will never have any issues with their heart, but some will only discover they have got a problem when they suffer a cardiac arrest.

Diagnosis rates are very low, so the vast majority of these anomalies will be undetected.

Prof Behr is researching the genetic causes of heart attacks

Prof Elijah Behr, a leading heart doctor at St George's, University of London, says that while inherited heart disorders are rare, "when you add them together they actually add up to a significant number".

"In fact, around 1,500 young people a year die suddenly in the UK from these inherited heart conditions. And that's the challenge - to identify those individuals and try to prevent those deaths," he adds.

Prof Behr is now working to determine the genetic causes of heart attacks, and hopes the information can be used to prevent sudden deaths in future.

Some doctors feel that mandatory screening for young people would help catch these conditions earlier, but others say more research needs to be done before it could be introduced.

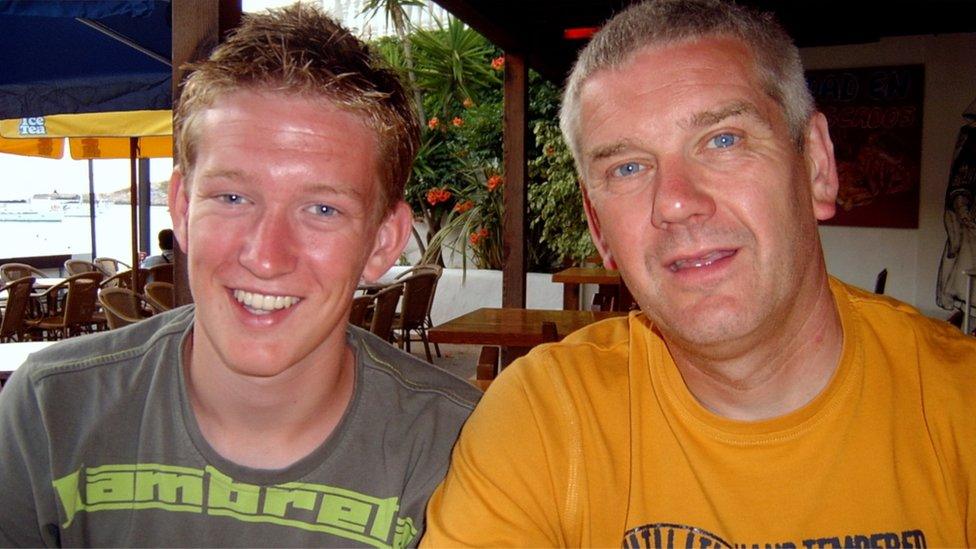

Dan Wilkinson, with his father Barry

In 2016, Barry and Gill Wilkinson's son Dan Wilkinson died after collapsing playing football.

He was aged 24 at the time and had lived an active lifestyle, having previously played for Hull City's youth team.

"He had a serious heart issue, but there was nothing to tell him, or us, that there was something wrong," his father reflects.

"Twenty-four hours before, we had FaceTimed and he was his usual self."

Dan had a condition known as ARVC (Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy), which weakens the wall of the heart and can lead to a cardiac arrest.

He collapsed during the second half while playing for non-league side Shaw Lane AFC.

Dan had previously played for Hull City's youth team

"My phone went and it was one of his team-mates," Barry remembers. "They said Dan had collapsed, would we be able to get there?"

By the time they did, he had died.

"You just go into shock," his mother Gill says.

Barry tries to stifle the tears as the couple discuss how they wish they could have told him they loved him one final time.

They have now started a charity, through which they have bought defibrillators for grassroots football clubs.

One has since been used to save the life of a 14-year-old boy playing for his local team in Yorkshire.

'Lucky to be alive'

Lora hopes that she can make a difference by speaking publicly about her own experiences.

"I really want young people to be aware that this could happen to them. Heart disease doesn't discriminate," she says.

She has been fitted with a defibrillator and pacemaker in her chest, which may one day be called upon to save her life.

But for now, she says she is trying to make the most of every day.

"I say 'yes' to the random outings my friends invite me to, because I never know if or when it could happen again and kill me this time.

"I just live life to the fullest now," she adds, "I'm lucky to be alive."

Follow the Victoria Derbyshire programme on Facebook, external and Twitter, external - and see more of our stories here.

- Published4 September 2018

- Published8 August 2018