Worry less about children's screen use, parents told

- Published

- comments

There is little evidence screen use for children is harmful in itself, guidance from leading paediatricians says.

Parents should worry less as long as they have gone through a checklist on the effect of screen time on their child, it says.

While the guidance avoids setting screen time limits, it recommends not using them in the hour before bedtime.

Experts say it is important that the use of devices does not replace sleep, exercising and time with family.

It was informed by a review of evidence published at the same time in the BMJ Open medical journal, external, and follows a debate around whether youngsters should have time on devices restricted.

Most of the evidence in the review was based on television screen time, but also included other screen use, such as phones and computers.

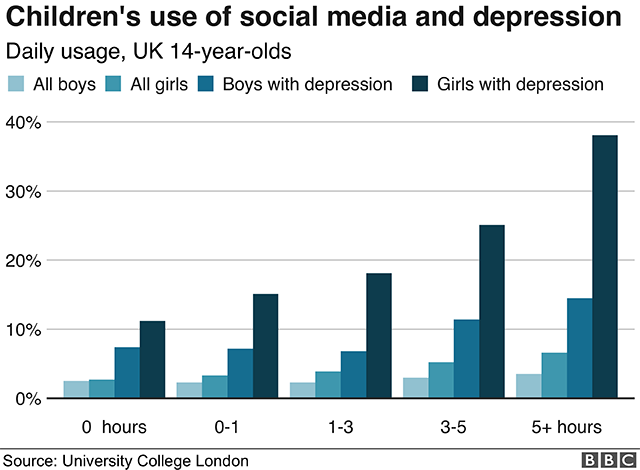

Meanwhile, a separate study has found that girls are twice as likely to show signs of depressive symptoms linked to social media use at age 14 compared with boys.

'No evidence of being toxic'

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH), which oversees the training of specialists in child medicine, has produced the guidance for under-18s.

It said there was no good evidence that time in front of a screen is "toxic" to health, as is sometimes claimed.

The review of evidence found associations between higher screen use and obesity and depression.

But the college looked at this and said it was not clear from the evidence if higher screen use was causing these problems or if people with these issues were more likely to spend more time on screens.

The review was carried out by experts at University College London, including RCPCH president Prof Russell Viner.

Parent and blogger Leyla Preston speaking on BBC Breakfast

The college said it was not setting time limits for children because there was not enough evidence that screen time was harmful to child health at any age.

Instead, it has published a series of questions to help families make decisions about their screen time use:

Is your family's screen time under control?

Does screen use interfere with what your family want to do?

Does screen use interfere with sleep?

Are you able to control snacking during screen time?

Dr Max Davie, officer for health promotion for the RCPCH, said phones, computers and tablets were a "great way to explore the world", but parents were often made to feel that there was something "indefinably wrong" about them.

He said: "We want to cut through that and say 'actually if you're doing OK and you've answered these questions of yourselves and you're happy, get on and live your life and stop worrying'.

"But if there are problems and you're having difficulties, screen time can be a contributing factor."

Dr Russell Viner, president of the RCPCH, told BBC Radio 4's Today programme "screens are part of modern life", adding: "The genie is out of the bottle - we cannot put it back."

He said: "We need to stick to advising parents to do what they do well, which is to balance the risks and benefits.

"One size doesn't fit all, parents need to think about what's useful and helpful for their child."

Parents should consider their own use of screens, if screen time is controlled in their family, and if excessive use is affecting their child's development and everyday life, he added.

What do parents say?

A number of parents have been in touch with the BBC to say they disagree with the guidance and feel it does not go far enough.

"There is absolutely no doubt in my mind that screen time is damaging school performance and sports performance and dangerously addictive," says Andy, whose son is 14.

Andy said he had restricted his son's screen time to Friday after school and Saturday, and, despite some "grumbling", there had been an improvement in school performance.

For tips on how to limit excessive screen time, click here.

'Grey area'

The recommendation that children should not use the devices in the hour before bedtime comes because of evidence that they can harm sleep.

The devices stimulate the brain, and the blue light produced by them can disrupt the body's secretion of the sleep hormone melatonin.

While there are night modes on many phones, computers and tablets, there is no evidence these are effective, the college said.

Overall, it found the effect of screen time on children's health was small when considered next to other factors like sleep, physical activity, eating, bullying and poverty.

It said there was a lack of evidence that screen time is beneficial for health or wellbeing.

Its guidance recommends that families negotiate screen time limits with their children based on individual needs and how much it impacts on sleep, as well as physical and social activities.

For infants and younger children, this will involve parents deciding what content they watch and for how long they use the devices.

As children get older, there should be a move towards them having autonomy over screen use, but this should be gradual and under the guidance of an adult, the college said.

Dr Davie added: "When it comes to screen time I think it is important to encourage parents to do what is right by their family.

"However, we know this is a grey area and parents want support, and that's why we have produced this guide.

"We suggest that age-appropriate boundaries are established, negotiated by parent and child, that everyone in the family understands."

The college called for better quality research to understand more about how the content on devices, and the context in which they are used, affects health outcomes.

Tips for parents:

Mealtimes can be good for screen-free zones

Mealtimes can be good opportunities for screen-free zones

If children's screen time use seems out of control, parents should consider intervening

Parents should think about their own screen use, including whether they use devices unconsciously too often

Younger children need face to face social interaction and screens are no substitute for this

Source: RCPCH, external

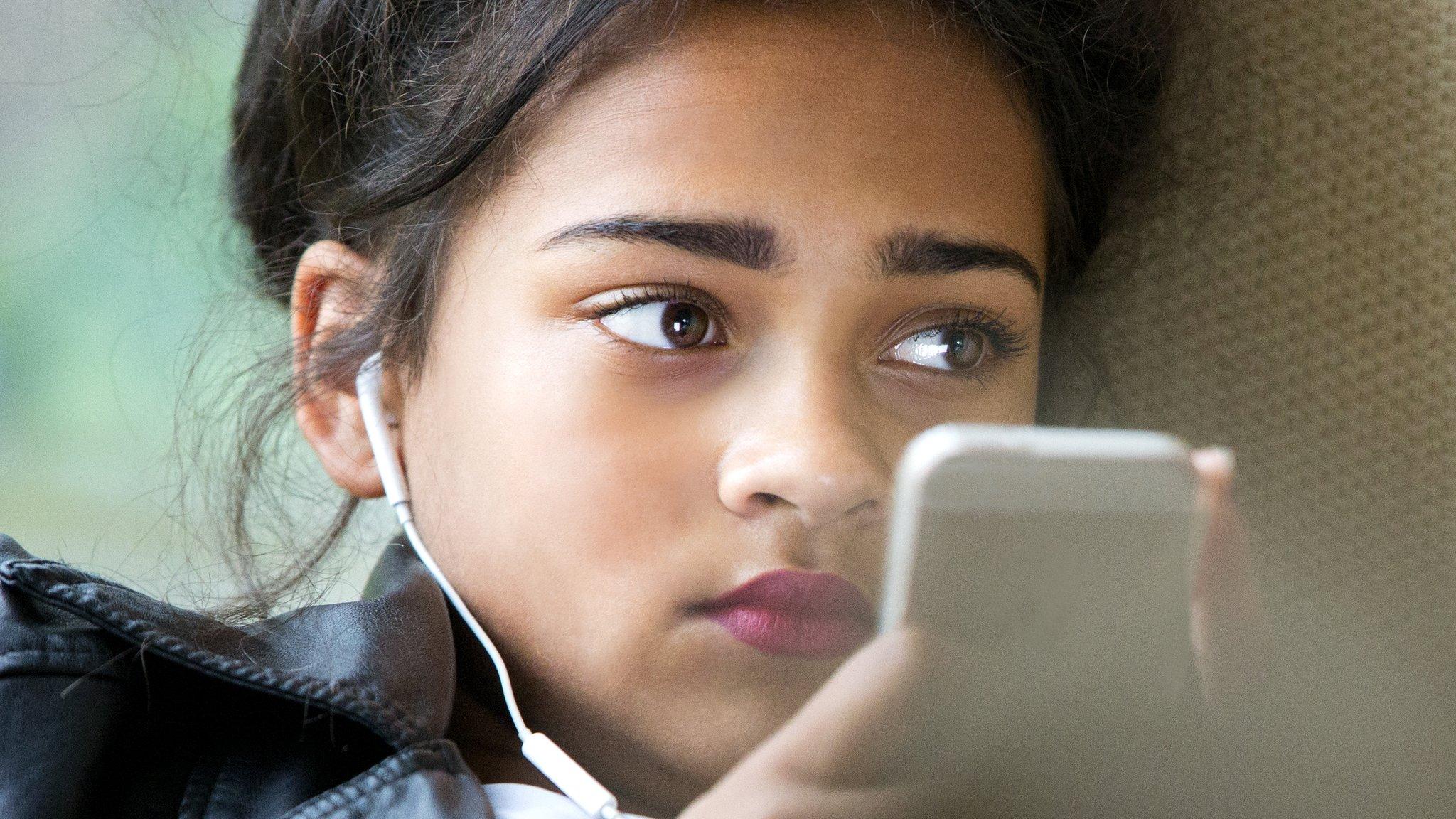

Social media and young people

The study on social media use and young people was carried out by experts at University College London and published in EClinicalMedicine, external.

It involved nearly 11,000 young people answering questionnaires on their social media use, online harassment, sleep patterns, self-esteem and body image.

It is separate to the RCPCH guidance on screen use and the review that informed it, neither of which looked at social media use.

Experts not involved in the social media study said it added to existing evidence that heavy social media use may be harmful for mental health.

But they called for more research to better understand if it causes depression, or if depressive people are more likely to use social media excessively.

- Published27 September 2018

- Published23 February 2018

- Published30 January 2018