A&E waits at worst level for 15 years in England

- Published

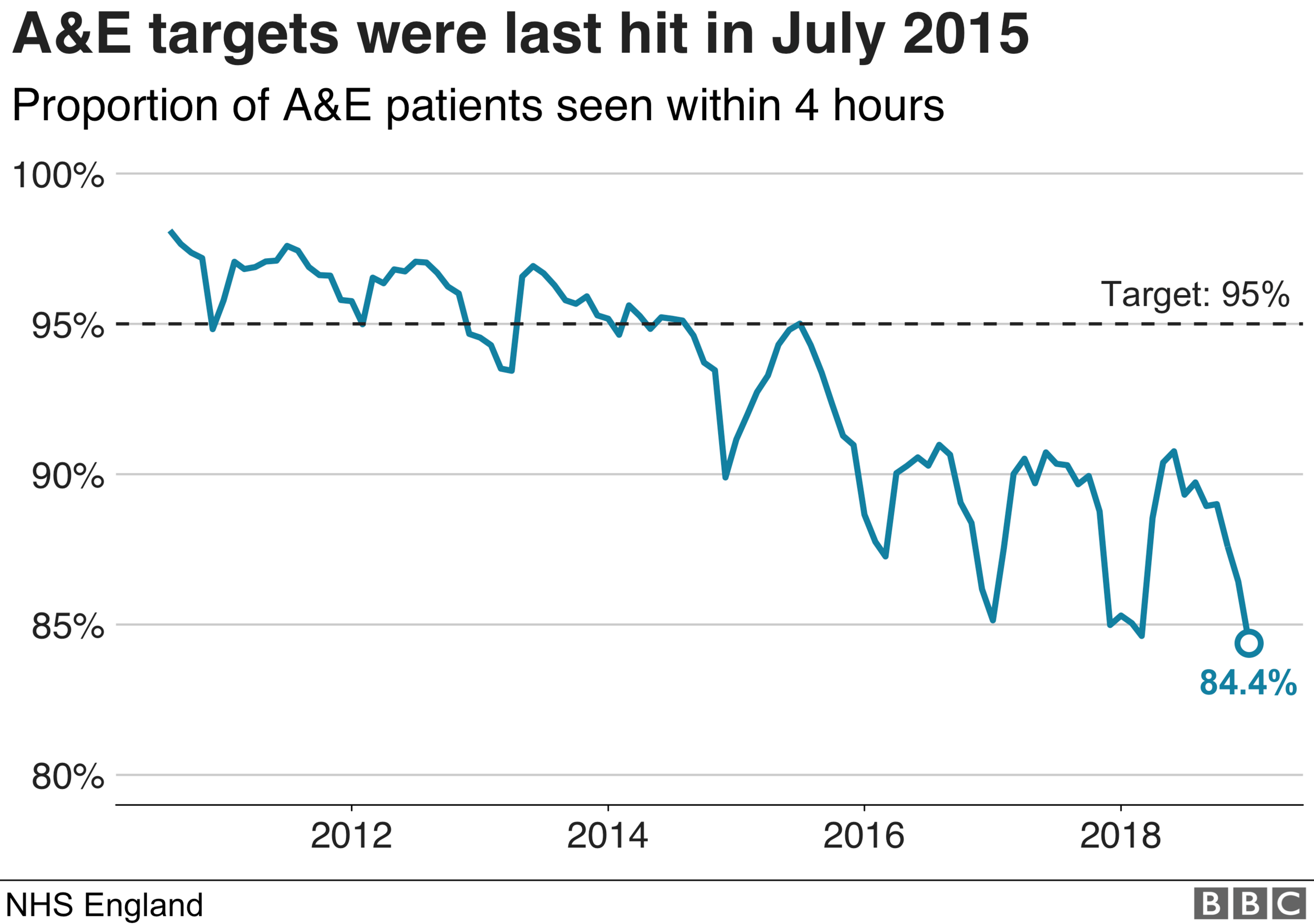

A&E waits in England have reached their worst level since the four-hour target was introduced in 2004.

The deterioration in performance came after hospitals appeared to be coping well in the early part of winter.

During January, only 84.4% of patients were treated or admitted in four hours - well below the 95% threshold.

It means nearly 330,000 patients waited longer than they should with hospitals reporting significant problems finding beds for those needing to be kept in.

More than 80,000 patients were kept waiting an extra four hours or more to be transferred to a ward after their wait in A&E.

These are known as trolley waits, since patients are left in temporary waiting areas while a bed is found.

All this comes despite relatively low levels of flu.

The last time the target was met was July 2015.

If you can't see the NHS Tracker, click or tap here, external.

What is the reaction?

Dr Nick Scriven, of the Society for Acute Medicine, said it was clear the NHS was under "severe strain".

He said hospitals had seen significant overcrowding with many intensive care units completely full.

He said this had had a knock-on effect on ambulances, which were being delayed dropping off patients at A&E.

"Although there is less minor illness associated with flu this year, there are more severely ill people than last year, which is putting an even bigger strain on the critical care facilities in our hospitals.

"Any NHS worker will tell you that the stresses and strains are very real and ongoing with no let-up in sight."

Prof John Appleby, chief economist of the Nuffield Trust think tank, said it was clear that the NHS was "fighting a losing battle" in trying to meet its commitments.

He added: "There is a risk that we lose sight of these problems as Brexit distracts us. This situation has a serious impact on hundreds of thousands of patients, and will be demoralising for many staff."

Is it all bad news?

An NHS England spokesman accepted there were significant pressures, but pointed out that in some respects performance had improved.

He said that when performance was combined with December, this winter was actually slightly better than last.

There are also more patients coming to A&E than there were last year, which needed to be taken into account, while the mass cancellation of non-emergency treatments that was ordered during last January did not happen this year.

There is also a sense that the wider system is working better.

Some patients face delays being discharged form hospital because there is a lack of community care available to support them.

These delays have fallen compared to two winters ago, suggesting council care teams and NHS services are in a better position to provide support to hospitals.

And in the coming years, the budget for the NHS is due to rise by more than 3% compared to the 1-2% it has seen since 2010.

What is happening in the rest of the UK?

Figures for January are not available yet for the other UK nations. But earlier in the winter, the data shows that all parts of the NHS were struggling and missing their A&E targets.

Performance in Wales and Northern Ireland was worse than it was in England, whereas Scotland was broadly similar.

And when you look at the other core targets, covering cancer care and routine operations, performance is below what it should be everywhere.

Dr Taj Hassan, president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, said poor performance was being "normalised", adding the system was in "chronic crisis mode".

"This does not allow staff to deliver the quality of care they would wish and patients should rightly expect."

- Published13 June 2019