NHS signals four-hour A&E target may end

- Published

- comments

The four-hour A&E target may be dropped under plans announced by NHS England.

NHS bosses have unveiled plans for an overhaul of the A&E target alongside changes to waiting times for cancer, mental health and planned operations.

It said the targets were becoming outdated. But it comes after many of them have been missed for years.

Instead of aiming to see and treat virtually all A&E patients in four hours, the sickest patients will be prioritised for quick treatment.

NHS England wants to see patients coming in with heart attacks, acute asthma, sepsis and stroke starting their care within an hour.

The changes will be piloted this year and, if successful, could be introduced in 2020.

The plans have been unveiled after NHS England was asked by the prime minister to look at the system of targets last year.

If you can't see the NHS Tracker, click or tap here, external.

Why is the A&E target being changed?

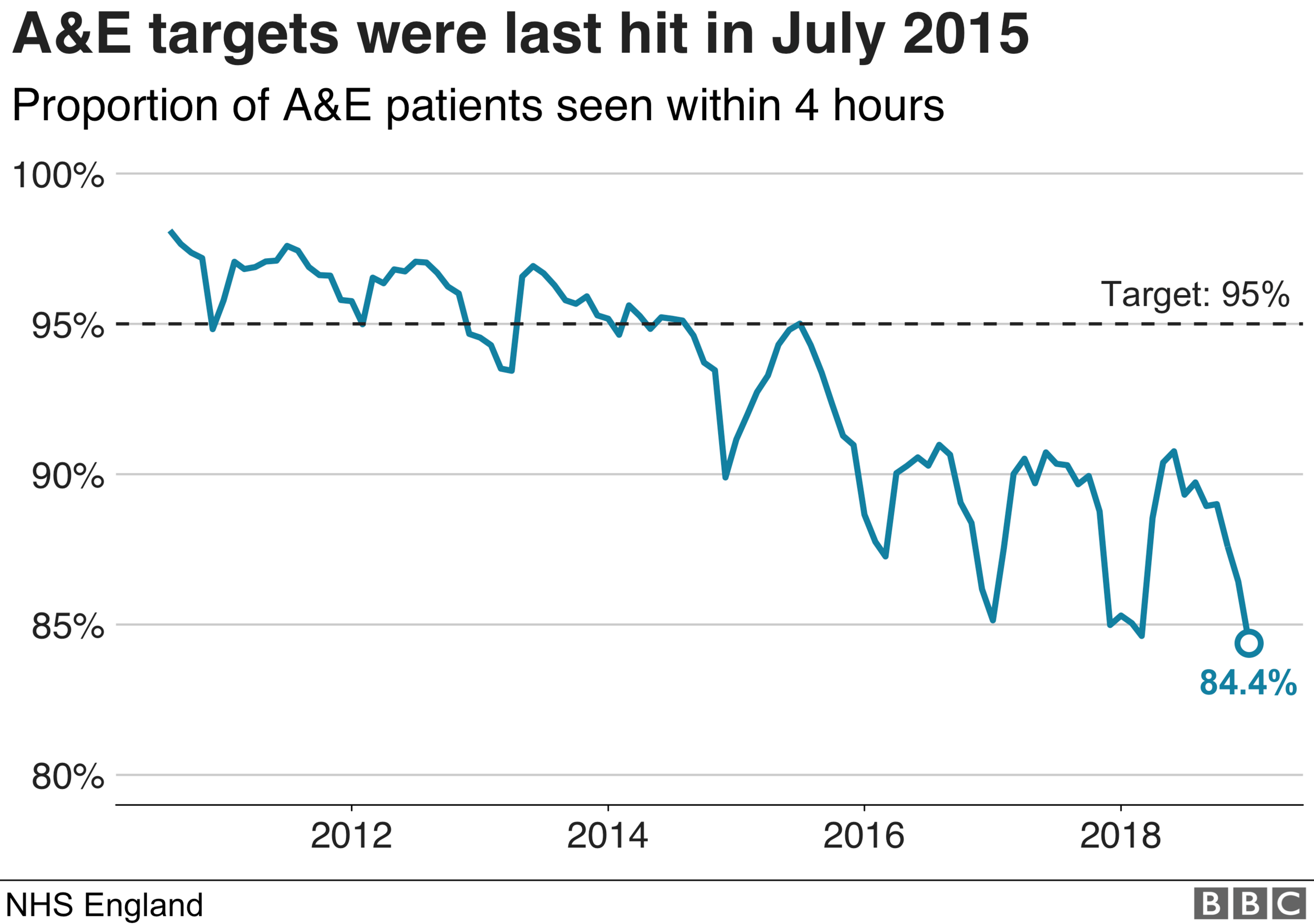

The four-hour target, which expects 95% of patients to be seen in time, was introduced in 2004 and has not been met since July 2015.

Last month, only two hospital trusts hit it.

NHS England said the current target seemed to be distorting priorities.

It pointed out that large numbers of patients were admitted into hospital just before the four-hour mark, which has the effect of "stopping the clock".

NHS England said hospitals appeared to be motivated by the target rather than doing what was best for the patient.

But it said a final decision over whether or not to definitely scrap it would not be made until after piloting takes places over the rest of the year.

How will this change what happens?

Currently, the target treats everyone the same - whether a patient has a sore thumb or has had a heart attack.

That, of course, does not mean staff do. All accident and emergency units have systems in place to prioritise the sickest patients.

It is just that how long they wait is not recorded and published publicly.

In doing this, the change will put pressure on those hospitals that are not seeing such patients quickly. That is obviously a benefit.

But for people with less urgent needs, there is concern that dropping the four-hour target could mean they wait longer.

NHS England plans to counter this by recording the average waits and introducing a new measure to record when all patients see a senior doctor or nurse.

But nonetheless the changes still send a clear signal about the pecking order - and, in an under pressure system, that could lead to "less important" cases waiting longer.

Not many people would argue with that if it is someone with a sore thumb. But if a patient has a broken bone or is bleeding and is in pain, that is likely to be viewed differently.

What is happening to the other targets?

The NHS will also move towards average waiting times for planned operations, such as knee and hip replacements.

Currently 92% of patients should be seen in 18 weeks. But that has not been met since February 2016.

Cancer targets - for which there are nine separate ones - will be simplified so that there are two key targets for treatment starting on top of the incoming 28-day goal for diagnosis - something that is not currently measured.

Meanwhile, new targets will be introduced for mental health care with the goal of ensuring that everyone who needs urgent crisis care in the community receives it within 24 hours.

Access to other community mental health services - for children and adults - will be expected in four weeks. This is the first time that these services will have had targets attached to them.

NHS England medical director Stephen Powis said: "Now is the right time to look again at the old targets, which have such a big influence on how care is delivered, to make sure they take account of the latest treatments and techniques and support, not hinder, staff to deliver the kind of responsive, high-quality services that people want to see."

What has been the reaction?

Many groups, including medical royal colleges, regulators and patient groups have broadly welcomed the plans.

Prof Ted Baker, the chief inspector of hospitals at the Care Quality Commission, said that while the four-hour target had been "valuable" in focusing efforts on improving emergency care, it was the right time to find a better way to measure performance.

"Emergency departments need a set of standards which give priority to patients with life-threatening conditions."

But the Royal College of Emergency Medicine said it was against the four-hour target being scrapped and instead said it should survive alongside the new measures.

"We are keen to ensure that any changes are not imposed due to political will, but are developed responsibly, collaboratively and are based upon clinical expert consensus in the best interests of patients," added college president Dr Taj Hassan.

Shadow Health Secretary Jonathan Ashworth said there was a concern the changes could lead to "the return to the bad old days of long waits".

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have a similar four-hour target, but there are no plans to change it. The way the other targets work is quite different.

- Published13 June 2019