What is the infected blood scandal and how much compensation will victims get?

- Published

The government has said it is making "substantial changes" to the compensation scheme for thousands of victims of the infected blood scandal.

The announcement was made after the payment scheme was heavily criticised in a report by the chair of the public inquiry into the disaster, Sir Brian Langstaff.

More than 30,000 people in the UK were infected with HIV and hepatitis C after being given contaminated blood products in the 1970s and 1980s.

As many as 140,000 bereaved parents, children and siblings of victims may also be able to claim compensation.

Who was given infected blood and how many died?

Two main groups of NHS patients were affected by what has been called the biggest treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

One group was haemophiliacs - and those with similar disorders - who have a rare genetic condition which means their blood does not clot properly, external.

People with haemophilia A have a shortage of a clotting agent called Factor VIII, while people with haemophilia B do not have enough Factor IX.

In the 1970s, a new treatment using donated human blood plasma was developed to replace these clotting agents.

But entire batches were contaminated with deadly viruses.

After being given the infected treatments, about 1,250 people in the UK with bleeding disorders went on to develop both HIV and hepatitis C, including 380 children.

'We were known locally as the Aids family'

About two-thirds later died of Aids-related illnesses. Some unintentionally gave HIV to their partners.

Another 2,400 to 5,000 people developed hepatitis C on its own, which can cause cirrhosis and liver cancer.

It is difficult to know the exact number of people infected with hepatitis C, partly because it can take decades for symptoms to appear.

A second group of patients was given contaminated blood transfusions after childbirth, surgery or other medical treatment between 1970 and 1991.

The inquiry estimates that between 80 and 100 of these people were infected with HIV, and about 27,000 with hepatitis C.

In total, it is thought about 2,900 people have died.

How much compensation will infected blood victims get?

In October 2024, Chancellor Rachel Reeves said that the government had set aside £11.8bn to pay compensation to victims.

It set up an independent arms-length body called the Infected Blood Compensation Authority (IBCA), external to administer payments.

Both those directly infected by contaminated blood products and those affected by the scandal - such as partners, parents, children and siblings - can make claims.

Payments are exempt from tax, and do not affect benefits.

The final amounts for individuals are assessed against five criteria: harm caused, social impact from stigma and isolation, impact on autonomy and private life, care costs and financial loss.

After the inquiry published its final report in May 2024, the then-Conservative government suggested how much people might receive, external:

a person infected with HIV could expect to get between £2.2m and £2.6m

those with a chronic hepatitis C infection, defined as lasting more than six months, could expect between £665,000 and £810,000

the partner of someone infected with HIV who is still alive today could expect about £110,000, while a child could get £55,000

Compensation payments will also go to the estate of infected people who have died.

How much compensation has already been paid?

In late 2022, following advice from the inquiry, the previous Conservative government made interim payments of £100,000 each to about 4,000 surviving victims and bereaved partners.

A second interim payment of £210,000 was paid to those infected in June 2024.

The Labour government has since said more relatives of those who died could also apply for a series of interim payments totalling £310,000.

As of 17 July:

More than 2,200 people have been invited to claim - and 1,900 have begun the process

More than 800 compensation payments totalling £602m have been offered

587 compensation payments totalling £412m have been made

The scheme is prioritising payments for those who have less than 12 months left to live due to any medical condition, external.

Victims and their relatives have criticised the time taken to make payments, and what they say is a lack of transparency.

What has the inquiry now said about compensation?

Unusually, Sir Brian re-opened the inquiry on 7 and 8 May to take further evidence about the speed of compensation payments. He said this reflected the gravity of concerns expressed to him.

His additional report, based on that evidence, argues that the delay in providing compensation to victims has created "an injustice all of its own".

He said the number of people who have been compensated to date was "profoundly unsatisfactory" and called for "faster and fairer" payments to victims.

Responding in parliament on 21 July, the government said it would immediately make seven of the 16 changes recommended, with the others subject to consultation with victims.

IBCA said it would separately accept all 11 recommendations under its remit.

The changes include:

A new system will be created allowing people to register for compensation rather than wait to be invited

Support payments for partners of those who died in the scandal will be reinstated until their compensation claim is finalised

People infected with HIV before a 1982 cut-off date will now be able to claim compensation whereas before they were ineligible

The amount of a supplementary payment for victims subject to unethical medical research will be reviewed, along with which patients qualify

What did the main infected blood inquiry report say?

Announcing its findings in May 2024, the inquiry said victims had been failed "not once, but repeatedly", and that the risk of viral infections in blood products had been known since 1948.

Inquiry chairman Sir Brian said there had been a lack of openness from the authorities and elements of "downright deception", including the destruction of documents.

"This disaster was not an accident," said Sir Brian. "The infections happened because those in authority - doctors, the blood services and successive governments - did not put patient safety first."

The Inquiry report, external said:

too little was done to stop importing blood products from abroad, which used blood from high-risk donors such as prisoners and drug addicts

in the UK, blood donations were accepted from high-risk groups such as prisoners until 1986

blood products were not heat-treated to eliminate HIV until the end of 1985, although the risks were known in 1982

there was too little testing to reduce the risk of hepatitis, from the 1970s onwards

How did the infected blood scandal happen?

In the 1970s, the UK was struggling to meet the demand for blood-clotting treatments, so imported supplies from the US.

But much of the blood was bought from high-risk donors such as prison inmates and drug-users.

Factor VIII was made by pooling plasma from tens of thousands of donors.

If just one was carrying a virus, the entire batch could be contaminated.

UK blood donations were not routinely screened for hepatitis C until 1991, 18 months after the virus was first identified.

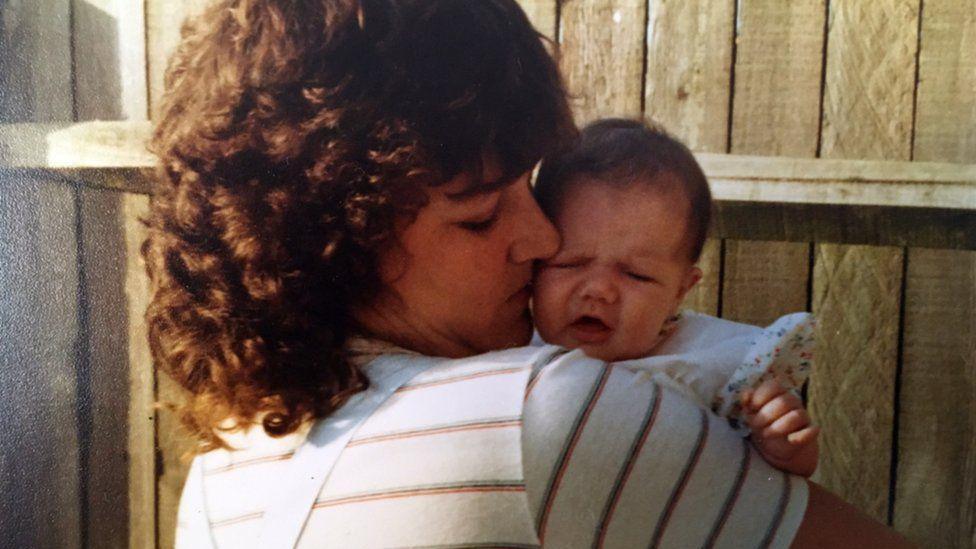

Jackie Britton, from Portsmouth, was infected with hepatitis C through a transfusion after the birth of her daughter in 1983

When did the authorities know about infected blood?

By the mid-1970s, there were repeated warnings that imported US Factor VIII carried a greater risk of infection.

However, attempts to make the UK more self-sufficient in blood products failed, so the NHS continued using foreign supplies.

Campaigners say haemophiliacs could have been offered an alternative treatment called Cryoprecipitate. This was much harder to administer, but was made from the blood plasma of a single donor, lowering the infection risk.

BBC News has also uncovered evidence that children were infected with hepatitis C and HIV after being placed on clinical trials of new treatments - often, without their family's consent.

As late as November 1983, the government insisted there was no "conclusive proof" that HIV could be transmitted in blood, a line robustly defended by former Conservative health minister Ken Clarke when he appeared before the inquiry.

Carolyn Challis: "I got through two life-threatening rounds of cancer only to be given another life-threatening illness"

What happened in other countries affected by infected blood?

Many other countries were affected, although some - including Finland - continued using older treatments until much later rather than switch to Factor VIII, which minimised HIV infections, external.

Delivering the findings of the inquiry, Sir Brian criticised UK government claims in the 1990s that screening for hepatitis C began as soon as the technology was available.

He said that 23 other countries - including Japan, Finland and Spain - introduced the screening before the UK.

In the US, companies that supplied infected products have paid out millions in out-of-court settlements.

Politicians and drug companies have also been convicted of negligence in countries including France and Japan.

In his evidence to the inquiry, former health secretary Andy Burnham suggested there may be grounds for charges of corporate manslaughter in the UK, external.