Could music festivals be good for your health?

- Published

- comments

Many festival-goers get up early to take part in workshops and classes

Millions of people around the world go to music festivals each year. At one time, they were seen as encouraging heavy drinking and drug-taking while providing poor facilities and bad food. But now organisers are more focused on festival-goers' wellbeing.

"The music is great, it's educational and it's therapy," says Marta Pibernat, from Catalonia in Spain.

"But we do end up drinking more than we should," admits her friend, Patricia Torne, who is also from Catalonia, but lives in the UK.

It is Friday morning and we are in a field in rural Wiltshire, in southwest England, where the two women and several hundred other people have just taken part in a 90-minute yoga workshop.

We are at the Womad world music festival, where performers such as Macy Gray, reggae star Ziggy Marley and Malian singer Salif Keita are performing over the four-day event to a total of 39,000 people.

The American R&B and soul singer Macy Gray was one of the headliners at this year's Womad

There are workshops, talks and therapies, along with exotic and familiar foods.

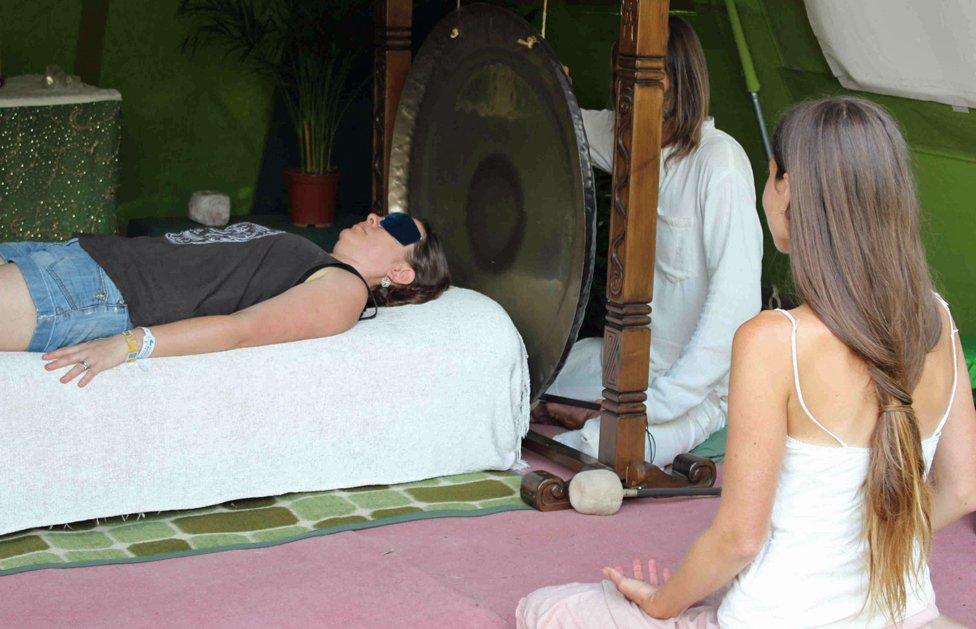

James Mowbray, from London, has just had a gong bath when I meet him.

Massages, reiki, reflexology and inversion therapy are all on offer, while two shamans offer to remove "ancestral traumas from the vibrational field of your DNA".

Mowbray lies on his back on a couch while two therapists gently bathe him in the sound of their gongs.

"It's extremely pleasurable and relaxing," he says of the 30-minute session, which cost £40 ($49).

"I used to go to dance music festivals, which are not necessarily good for your health," he adds, referring to their reputation for drugs and overindulgence.

Gong baths are among the many therapies available at festivals

The health benefits of listening to live music are borne out by studies.

"We found that going to concerts significantly reduces the levels of the stress hormone cortisol," says Daisy Fancourt, associate professor in epidemiology at University College London.

They took saliva samples from people attending a classical and a pop concert to compare stress levels.

"Both groups were biologically calmer afterwards. That suggests it's more about the event rather than the type of music.

Her studies also found that going to live music events could help reduce the risk of developing depression and preserve cognition in the over-50s.

The reggae artist Ziggy Marley believes festivals can benefit the collective wellbeing

Julie Ballantyne, of the University of Queensland, has studied the effects on people's wellbeing of music festivals in Australia.

"The experience of being separated from everyday life prompts people to reflect and spend time on themselves and this is important for their wellbeing," says the associate professor of music education.

"But we also found that if they had a positive social experience with friends, their subjective, psychological and social wellbeing were all the more impacted."

She says that bad experiences, such as drinking too much alcohol, being jostled in big crowds, poor toilet and shower facilities or queuing, can reduce the benefits.

Ziggy Marley tells me that festivals such as Womad are good for the collective wellbeing. "They represent the potential of the world. Thousands of people together in unity," he says.

Festival-goers at Womad can take part in many different workshops, such as the kora or African harp

But not everyone has a good time at festivals.

"If you aren't enjoying it and everyone else around you is, that could make you feel worse," says Dr Chris Howes, the founder of the charity Festival Medical Services (FMS).

"That's why we have psychiatrists and mental health nurses on site and work with welfare services," he tells me in the medical tent at Womad.

Using volunteers, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists and paramedics, FMS now also works at 11 other UK festivals, including Reading.

The World of Wellbeing at Womad is situated in the arboretum

"At Reading, you get a lot of young people who are away from home for the first time," says Dr Howes. "Sometimes they just need a cuddle."

He says that around 10% of the cases they deal with at festivals involve mental health or psychiatric problems.

"We see all the medical conditions you would expect in life from cardiac arrests to burns from barbecues and fires, to sunburn. We see an upswing in stomach problems towards the end of festivals as food people have brought starts to go off.

"I've delivered one or two babies in caravans at Glastonbury in the past and a festival is not an ideal place to have a baby," Dr Howes adds.

He says they see relatively few drink and drug-related problems.

Being in a crowd can expose you to infectious illnesses

He says festival-goers should make sure their immunisations for things such as measles and meningitis are up to date.

"The close proximity of people means epidemics can spread very quickly," Dr Howes adds.

"The truth is there is a healthy and an unhealthy side to music festivals," says Jeet-Kei Leung from Vancouver in Canada.

He has been involved in festivals across the world for 20 years as a producer, DJ and documentary filmmaker and is particularly interested in what he calls "transformational" ones, such as Burning Man in the Nevada desert.

The Burning Man Festival in Nevada says it is a "network of dreamers and doers"

He says transformational festivals support personal and community growth, offer workshops and health practices and often having a non-religious, spiritual side.

But he says that some transformational festivals are what are known as "ragers".

"At ragers, people are partying really hard and there could be a relatively high use of intoxicants," he says.

"Overall festivals are good for your health and most people go home recharged and reinvigorated," Dr Howes says. "We do our best to pick up the pieces when it goes wrong."

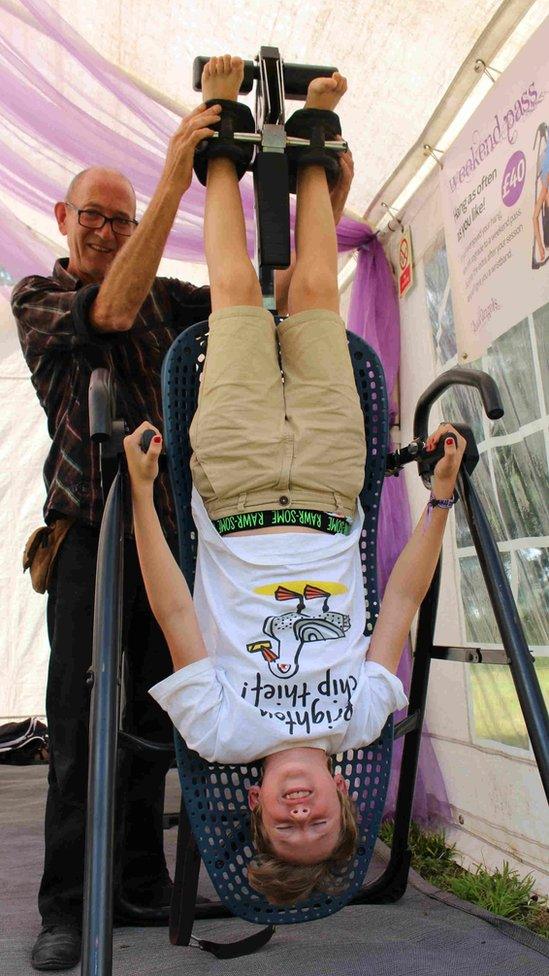

Inversion therapy is a form of traction aimed at easing back problems