Defeat malaria in a generation - here's how

- Published

The world could be free of malaria - one of the oldest and deadliest diseases to affect humanity - within a generation, a major report says.

Each year there are still more than 200 million cases of the disease, which mostly kills young children.

The report says eradicating malaria is no longer a distant dream, but wiping out the parasite will probably need an extra $2bn (£1.6bn) of annual funding.

Experts say eradication is a "goal of epic proportions".

What is malaria?

Malaria is a disease caused by Plasmodium parasites.

These are spread from person to person by the bite of female mosquitoes in search of a blood meal.

Once infected, people become very sick with a severe fever and shaking chills.

The malaria parasites are spread by mosquiotes

The parasites infect cells in the liver and red blood cells, and other symptoms include anaemia.

Eventually the disease takes a toll on the whole body, including the brain, and can be fatal.

Around 435,000 people - mostly children - die from malaria each year.

How is it going so far?

The world has already made huge progress against malaria.

Since 2000:

the number of countries with malaria has fallen from 106 to 86

cases have fallen by 36%

the death rate has fallen by 60%

This is largely down to widespread access to ways of preventing mosquito bites, such as bed nets treated with insecticide, and better drugs for treating people who are infected.

Sleeping under insecticide-treated bed nets prevents mosquitoes biting at night

"Despite unprecedented progress, malaria continues to strip communities around the world of promise and economic potential," said Dr Winnie Mpanju-Shumbusho, one of the report authors.

"This is particularly true in Africa, where just five countries account for nearly half of the global burden."

Why is this report important?

Eradicating malaria - effectively wiping it off the face of the planet - would be a monumental achievement.

The report was commissioned by the World Health Organization three years ago to assess how feasible it would be, and how much it would cost.

Forty-one of the world's leading malaria experts - ranging from scientists to economists - have concluded that it can be done by 2050.

Their report, published in the Lancet, external, is being described as "the first of its kind".

"For too long, malaria eradication has been a distant dream, but now we have evidence that malaria can and should be eradicated by 2050," said Sir Richard Feachem, one of the report authors.

"This report shows that eradication is possible within a generation."

However, he warned it would take "bold action" in order to achieve the goal.

Watch Pallab Ghosh's report on whether "serenading" mosquitoes could help stop malaria?

So what will it take?

The report estimates that based on current trends, the world will be "largely free of malaria" by 2050.

But there will still be a stubborn belt of malaria across Africa, stretching from Senegal in the north-west to Mozambique in the south-east.

To reach eradication by 2050 will require current technologies to be used more effectively, and the development of new ways of tackling the disease, the report says.

This could include the "game-changing potential" of gene-drive technologies.

Unlike the normal rules of genetic inheritance, gene-drives force a gene (a piece of DNA) to spread through the population.

It could in theory make mosquitoes infertile and cause their populations to collapse, or make them resistant to the parasite.

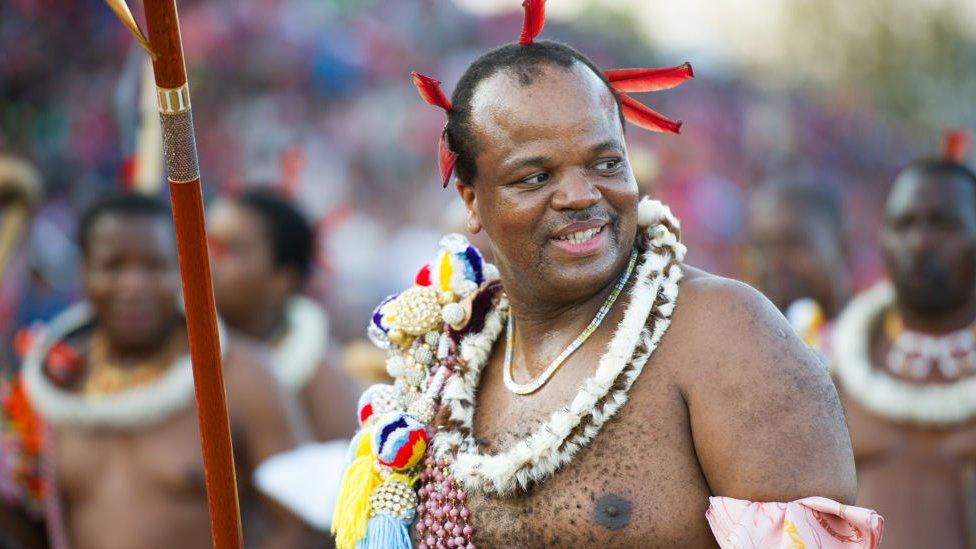

King Mswati III of Eswatini

King Mswati III of Eswatini (formerly Swaziland) and chair of the African Leaders Malaria Alliance said: "Malaria eradication within a generation is ambitious, achievable and necessary.

"The struggle has been constant to keep up with the malaria mosquito and the parasite, both of which are evolving to evade the effect of malaria interventions.

"We must make sure that innovation is prioritised."

How much is this all going to cost?

The report estimates around $4.3bn (£3.5bn) is spent on malaria every year at the moment.

But it would need a further $2bn a year in order to rid the world of malaria by 2050.

The authors say there is also a cost of business as usual, in terms of lives lost and the constant struggle against the malaria parasite and the mosquitoes evolving resistance to drugs and insecticides.

The report concludes that getting an extra $2bn a year will be "challenging" but the social and economic benefits of eradicating malaria would "greatly exceed the costs".

The malaria vaccine, which is starting to be rolled out in large trials, should help save lives

Will malaria be eradicated by 2050?

Eradicating a disease is a challenge on a global scale (literally).

It has happened only once before for an infection in people - smallpox was declared eradicated in 1980.

It required a huge effort and a highly effective vaccine to get the job done.

But there is a reason smallpox is the only one, and the history of poliovirus shows how challenging eradication can be.

In the wake of the success with smallpox, there was widespread hope polio would be rapidly consigned to history too, and a target of eradication by the year 2000, external was set.

Two decades after that initial target and cases have been cut by 99%. However, the last 1% has proved to be incredibly difficult.

Nigeria, and as a result the whole of Africa, is on the cusp of eliminating polio, but getting the vaccine to every child in the two remaining endemic countries (Pakistan and Afghanistan) is still proving difficult.

What has the reaction been?

"Eradicating malaria has been one of the ultimate public health goals for a century, it is also proving to be one the greatest challenges," said Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus, the director general of the World Health Organization.

"But we will not achieve eradication within this timeframe with the currently available tools and approaches - most of which were developed in the past century or even earlier."

Dr Fred Binka, from the University of Health and Allied Sciences in Ghana, said: "Malaria eradication is a goal of epic proportions.

"It will require ambition, commitment and partnership like never before, but we know that its return is worth the investment, not only by saving lives in perpetuity, but also improving human welfare, strengthening economies and contributing to a healthier, safer and more equitable world."

Follow James on Twitter, external.