Egg-freezing: What's the success rate?

- Published

- comments

The fertility expert, Lord Robert Winston, appeared on BBC Radio 4's Today programme to discuss the campaign to relax the current ten-year limit on freezing eggs.

Lord Winston, who is professor of fertility studies at Imperial College London, warned that it was "a very unsuccessful technology" and said: "The number of eggs that actually result in a pregnancy after freezing is about 1%." He later clarified he was referring to live births.

But the body which regulates fertility treatment in the UK - the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) - puts the success rate at closer to one in five - a far better chance than the one in a hundred Lord Winston suggests.

So, why the different figures?

It's because the two are measuring the success rate based on different stages of fertility treatment.

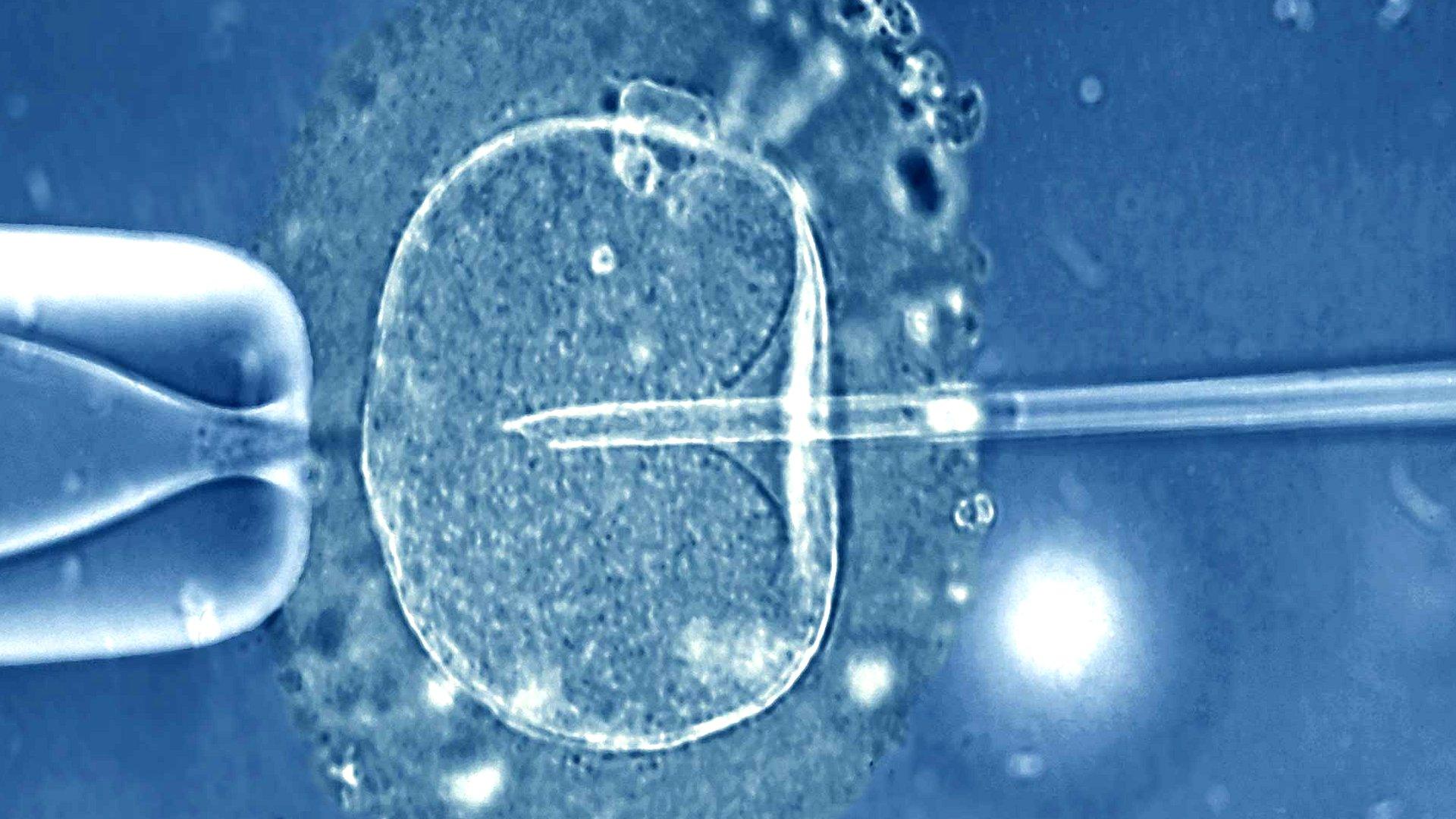

An IVF cycle involving frozen eggs goes something like this:

Eggs which were previously frozen and stored are thawed

The ones that survive the thawing will be fertilised with sperm

Eggs that are successfully fertilised start to develop into embryos

Of the embryos that survive, usually one or two (up to a maximum of three for women over 40) will be transferred to the womb

Lord Winston's 1% figure was referring to the proportion of all frozen eggs thawed for use in fertility treatment which result in a pregnancy and subsequent live birth. Data from the HFEA from 2016, given to him in response to a question in the House of Lords, puts the pregnancy rate at 1.8%, external.

There was no data on live births available for 2016 at the time Lord Winston asked the question, but looking at 2015 data, 2% of all thawed eggs ended up as pregnancies and 0.7% as live births.

The HFEA measures success based on how many embryos (developed from frozen eggs) result in a live birth. Using this measure, 19% of IVF treatments using a patient's own frozen eggs were successful in 2017.

Both measures miss out some information

If you're thinking of freezing your eggs, you probably want to know how likely you are to get pregnant from a round of IVF. But looking at the success rate for each individual egg (the much lower number) ignores the fact that a round of IVF will involve several eggs.

And there's an expected "attrition" that happens through the course of treatment, explains Dr Sarah Martins Da Silva, an NHS gynaecologist and lecturer in reproductive medicine at the University of Dundee.

"Not every egg makes an embryo, not every embryo makes a pregnancy and not every pregnancy makes a baby," she says. From thawing, to fertilisation, to development into an embryo, to transferring the embryo into a womb, eggs are lost at each stage, and there is never any intention that every egg in a treatment cycle will be used.

Ali's egg freezing journey

But the HFEA data only looks at the birth rate once an embryo is transferred - and not every treatment cycle will result in an embryo. That means the HFEA's success rate could be lower if it included women whose IVF cycle fails even before an embryo can be implanted

In 2016, when Lord Winston asked for the data:

1,204 eggs were thawed - but we don't know how many women or rounds of IVF that represents

Of these, 590 eggs (49%) were fertilised

Of the 590 eggs fertilised, 179 (30%) were transferred back to a patient

Out of the embryos transferred, 22 resulted in a pregnancy (13%)

That year, 6,199 were frozen but these are unlikely to be the same eggs being thawed

There is more recent data on embryo transfers, but the HFEA does not routinely publish the above data on thawing and fertilisation.

And this still doesn't tell you about the success rate for individual women. That's an average, but within that group some women may have all the eggs she thawed survive, while others may have none.

Your chances of becoming pregnant also heavily depend on your age at the time your eggs were frozen, and your general health.

Women who were under 35 at the time their eggs were frozen have the highest number of births per treatment cycle, according to HFEA data, and this rate declines with age. So, a younger, healthier woman could have a higher chance than 19%.

The 19% figure will also include egg freezing cycles funded by the NHS for medical reasons (about one fifth of the total). Most of these will be women who are already unwell - often using egg-freezing to preserve the possibility of having children after going through fertility-damaging treatments like chemotherapy - and so might have a lower chance of pregnancy.

The rate can vary between clinics depending on their mix of patients. For example, gynaecologist Jara Ben-Nagi said the success rate at her own practice the Centre for Reproductive and Genetic Health was 27%.

The HFEA also points out that very small numbers of women in the UK who freeze their eggs actually go back to use them, so it's difficult to draw too firm a conclusion from such a small sample.

Sally Cheshire, who chairs the body said of the consultation to extend the 10-year storage limit that "the time is right to consider what a more appropriate storage limit could be that recognises both changes in science and in the way women are considering their fertility".