Are coronavirus tests flawed?

- Published

There are deep concerns laboratory tests are incorrectly telling people they are free of the coronavirus.

Stories in several countries suggest people are having up to six negative results before finally being diagnosed.

Meanwhile, officials in the epicentre of the epidemic, Hubei province, China, have started counting people with symptoms rather than using the tests for final confirmation.

As a result, nearly 15,000 new cases were reported on a single day - a quarter of all cases in this epidemic.

What are these tests and is there a problem with them?

They work by looking for the genetic code of the virus.

A sample is taken from the patient. Then, in the laboratory, the virus's genetic code (if it's there) is extracted and repeatedly copied, making tiny quantities vast and detectable.

These "RT-PCR" tests, widely used in medicine to diagnose viruses such as HIV and influenza, are normally highly reliable.

"They are very robust tests generally, with a low false-positive and a low false-negative rate," Dr Nathalie MacDermott, of King's College London, says.

But are things going wrong?

A study in the journal Radiology, external showed five out of 167 patients tested negative for the disease despite lung scans showing they were ill. They then tested positive for the virus at a later date.

And there are numerous anecdotal accounts.

These include that of Dr Li Wenliang, who first raised concerns about the disease and has been hailed as a hero in China after dying from it.

Dr Li posted a picture of himself on social media from his hospital bed, on 31 Jan. The next day, he said, he had been diagnosed for coronavirus

He said his test results had come back negative on multiple occasions before he had finally been diagnosed.

Chinese journalists have uncovered other cases of, external people testing negative six times before a seventh test confirmed they had the disease.

And similar issues have been raised in other affected countries, including Singapore and Thailand.

In the US, meanwhile, Dr Nancy Messonnier, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, says, external some of its tests are producing "inconclusive" results.

What might be going on?

One possible explanation is the tests are accurate and the patients do not have coronavirus at the time of testing

It is also cough, cold and flu season in China and patients may confuse these illnesses for coronavirus.

"The early signs of coronavirus are very similar to other respiratory viruses," Dr MacDermott says.

"Maybe they weren't infected when first tested.

"Then, over the course of time, they became infected and later tested positive for the coronavirus. That's a possibility."

Another option is the patients do have the coronavirus but it is at such an early stage, there is not enough to detect.

Even though RT-PCR tests massively expand the amount of genetic material, they need something to work from.

"But that doesn't make sense after six tests," Dr MacDermott says.

"With Ebola, we always waited 72 hours after a negative result to give the virus time."

Alternatively, there could be a problem with the way the tests are being conducted.

There are throat swabs and then there are throat swabs.

"Is it a dangle or a good rub?" asks Dr MacDermott.

And if the samples are not correctly stored and handled, the test may not work.

There has also been some discussion about whether doctors testing the back of the throat are looking in the wrong place.

This is a deep lung infection rather one in the nose and throat.

However, if a patient is coughing, then some virus should be being brought up to detect.

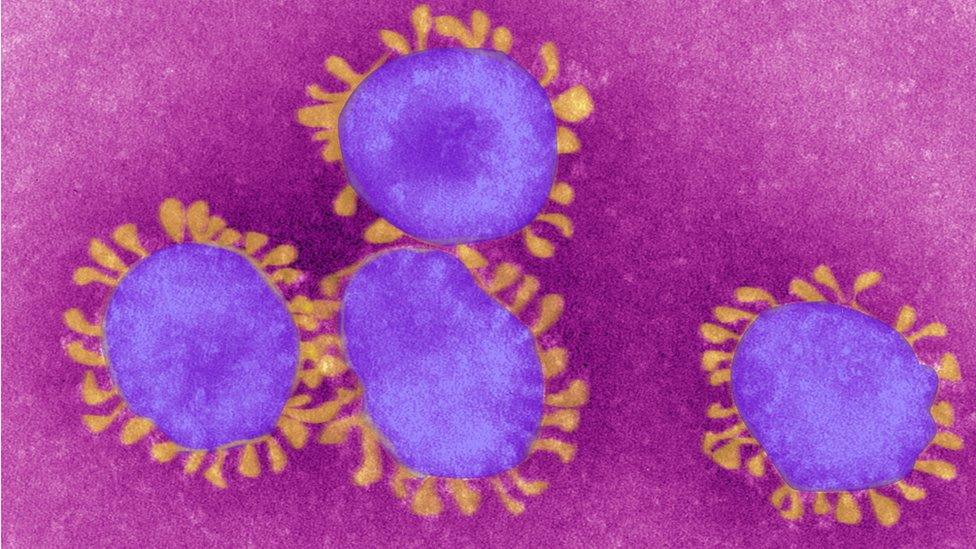

Coronaviruses are named for the tiny "crowns" that protrude from their surface

A final option is the RT-PCR test for the new coronavirus is based on flawed science.

In order to develop the test, researchers must first pick a section of the virus's genetic code.

This is known as the primer. It binds with the matching code in the virus and helps bulk it up. Scientists try to pick a region of the virus's code they do not think will mutate.

But if there is a poor match between the primer and the virus in the patient, then an infected patient could get a negative result.

At this stage, it is impossible to tell exactly what is going on so lessons for other countries are unclear.

"It is not going to change that much," Dr MacDermott says.

"But it flags up that you have to test people again if they continue to have symptoms."

Follow James on Twitter, external.