NHS 'took 18 months to help after suicide attempt'

- Published

Simon has struggled with his mental health over the past three decades

Poor treatment and aftercare for people who self-harm or attempt suicide is putting their lives at risk, the Royal College of Psychiatrists says.

Many patients treated in A&E for self-harm do not receive a full psychosocial assessment, external from a mental health professional to assess suicide risk.

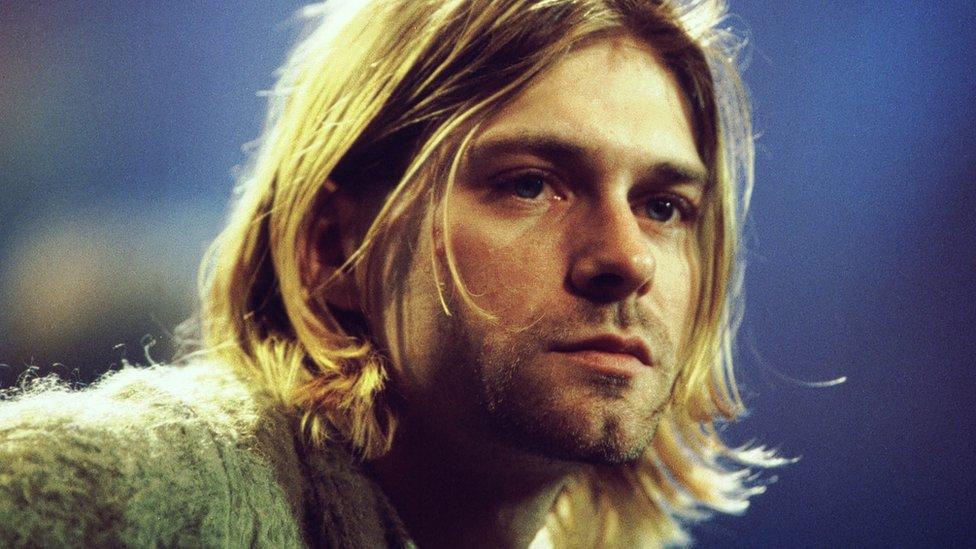

Simon Rose, who has attempted suicide many times, told BBC News it once took 18 months to receive aftercare.

NHS England said reducing suicide rates was an "NHS priority".

Simon's parents acted as foster carers to numerous children, and he would experience feelings of loss and abandonment every time a fostered sibling left.

"It took a couple of years of therapists poking in my head to get me to a point where I am able to see that I was deliberately keeping people at arm's length to avoid getting close to people who would subsequently leave," he said.

"I continued to hold people at arm's length into adulthood, wanting largely to be invisible.

"Always feeling inferior, always feeling negatively judged, I got to a point where I considered myself to be disposable.

"When my mood was low/is low, I struggle to deal with those feelings of inferiority.

"It is fair to say that my treatment within services has been patchy, which I think is the experience of most people that I talk to who have been in similar situations.

"There have been times when I have been pretty much left to my own devices, with very little support in keeping myself safe."

Depressive episodes

Last year, UK suicide rates rose for the first time since 2013, with people born in the 1960s and 1970s being the most vulnerable. The Office for National Statistics said changes to the way the figures are recorded may account for some of the rise.

Experts are now calling for all self-harm patients to be offered a safety plan - an agreed set of bespoke activities and guidelines to help them deal with depressive episodes.

But Simon, who is from Derbyshire, said: "After one of my first hospital admissions, I received a safety plan through the post 18 months after I had been discharged.

"When I struggle, I look for things that reinforce my negative view of myself - missing out on a safety plan on discharge reinforced that message that I am worthless.

"There have been times when I've been given a generic plan which has little or no relevance to me. And, truthfully, if it's not personal, for me it's pretty pointless

"For some, reaching out to a partner would be the first safe step. However, for others, that same action could have a negative effect.

"Everybody's individual journey is unique and the safety plans that are created need to be tailored for them."

'Propping up'

Another patient, in his 20s, from London, told BBC News: "I thought that I was going to be getting divorced and felt really really low.

"I noticed the signs and had a GP appointment in which the doctor said he would refer me for some counselling.

"About eight weeks later I got an email telling me that actually counselling referrals weren't available where I lived.

"In the meantime, I had found my own ways of propping myself up.

"But if I hadn't been able to do that, I don't really know where I'd have ended up."

'Let down'

Dr Huw Stone, who chairs the patients' safety group at the Royal College of Psychiatrists, said patients, especially those under 30, were being systematically let down in their most vulnerable state.

"With hospital admissions for self-harming under-30s more than doubling in the last 10 years, there has never been a more important time to ensure patients are getting the care that they need," he said.

An NHS England official said: "While suicide rates have decreased over the last 10 years, reducing them even further is an NHS priority and in the past three years, as part of our long-term plan, we have invested to ensure that every general hospital now has expert mental-health teams on hand for patients who have self-harmed."

If you or someone you know are feeling emotionally distressed, these organisations offer advice and support.

In addition, you can call the Samaritans free on 116 123 (UK and Ireland). Mind also has a confidential telephone helpline - 0300 123 339 (Monday-Friday, 09:00-18:00).

- Published13 August 2019

- Published18 January 2020