Coronavirus: The NHS workers wearing bin bags as protection

- Published

As the death toll from coronavirus continues to climb, hospitals across the UK are working flat out to create more intensive care beds for those who are critically ill. Speaking to the BBC, one intensive care doctor describes the crippling reality of a lack of support and equipment faced by some health-care workers in England.

Several healthcare workers in England have told the BBC of a lack of equipment in their hospitals. Warned against speaking to the media, they were unwilling to talk publicly. However, one intensive care doctor from the Midlands wanted to go on record. The BBC agreed to change her name in order to protect her identity.

Dr Roberts describes a hospital on the brink. Intensive care is already full of coronavirus (Covid-19) patients. All operations deemed non-urgent, even the cancer clinics, have been cancelled. There is a lack of staff, a lack of critical care beds, a shortage of basic antibiotics and ventilators.

All this, combined with the looming uncertainty of what will be the expected peak, estimated to hit the UK around 14-15 April, means hospital staff are already feeling the strain.

However, nothing Dr Roberts describes is quite as alarming as the fact that these medical professionals, who continue to care for critically ill patients for 13 hours every day, are having to resort to fashioning personal protective equipment (PPE) out of clinical waste bags, plastic aprons and borrowed skiing goggles.

Dr Roberts shown in the left picture, tying a bin bag covering the sides and back of her colleague's head

While the public attempts to keep to a social distance of two metres, many NHS staff are being asked to examine patients suspected of coronavirus at a distance of 20cm - without the proper protection.

With potentially fatal implications, Dr Roberts says several departments within her hospital are now so fearful of what's coming next, they have begun to hoard PPE for themselves.

"It's about being pragmatic. The nurses on ITU (Intensive Treatment Unit) need it now. They are doing procedures which risk aerosol spread of the virus. But they've been told to wear normal theatre hats, which have holes in them and don't provide any protection.

"It's wrong. And that's why we're having to put bin bags and aprons on our heads."

The government has acknowledged distribution problems, but says a national supply team, supported by the armed forces, is now "working around the clock" to deliver equipment.

NHS England also said more than one million respiratory face masks were delivered, external on 1 April, but with no mention of much-needed head protection and long-sleeved gowns.

Dr Roberts says her hospital has not received anything from the government, and what they do have is causing concern.

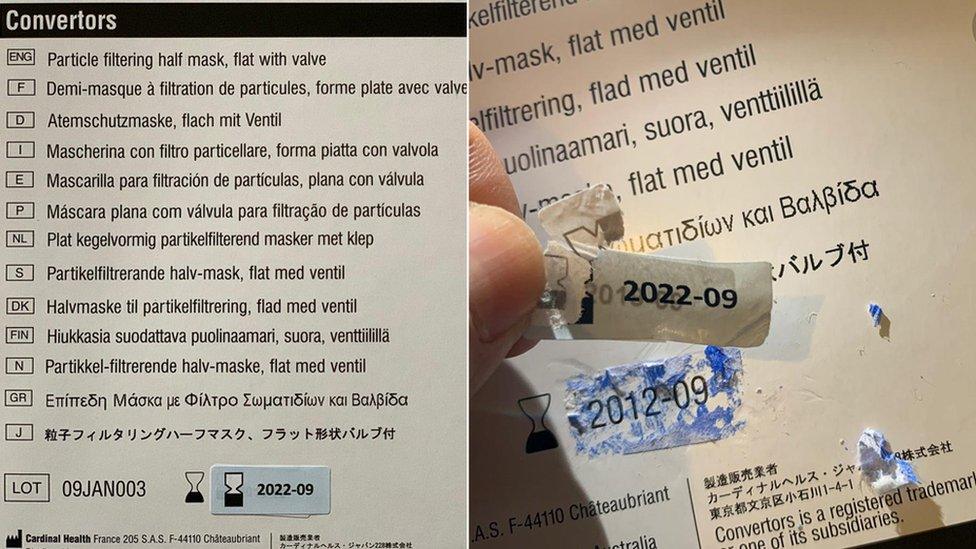

"The respiratory protection face masks we're using at the moment, they've all been relabelled with new best-before end dates. Yesterday I found one with three stickers on. The first said, expiry 2009. The second sticker, expiry 2013. And the third sticker on the very top said 2021."

Public Health England has said all stockpiled pieces of PPE [personal protective equipment] labelled with new expiry dates have "passed stringent tests", external and are "safe for use by NHS staff". But Dr Roberts says she is not convinced.

Dr Roberts pulls expiry date stickers from the packaging on a face mask

The Department of Health and Social Care also said it was "working closely with industry, the NHS, social care providers and the Army… If staff need to order more PPE there is a hotline in place".

It said its new guidance on PPE was in line with World Health Organization advice to "make sure all clinicians are aware of what they should be wearing".

Currently ventilated and under Dr Roberts' care are three of her colleagues, all of whom have tested positive for coronavirus. One is an intensive care doctor working on a Covid ward, who, like Dr Roberts, only had access to inadequate protection.

The other two were both working on non-Covid wards and therefore were wearing no PPE. However, given their symptoms, Dr Roberts believes both of them contracted the virus while at work.

Although colleagues continue to visit, as with all other patients, no relatives are allowed anywhere within the hospital.

"The hardest thing at the moment is having to tell families you are withdrawing care, over the phone. Telling them their relatives are dying or have died but we can't let you come and see them," says Dr Roberts.

"Normally you can say to their relative who's at the bedside, 'We're going to do everything we can', but I haven't felt able to say that, because at the moment, I can't.

"I can't necessarily give them the best care on a ventilator, I can't guarantee the best nursing care, because the best nurses are being stretched four ways. We're running out of antibiotics, and I can't guarantee all the treatments that I know would help them."

NHS England says it has no record of how many medical professionals have been admitted to hospital after contracting coronavirus at work.

However, the two hardest-hit countries in Europe are counting. Spain's emergency health minister announced on 27 March that more than 9,400 health-care workers had tested positive, and in Italy, as of 30 March, more than 6,414 medical professionals were reported to have been infected.

In the UK, several health workers are known to have died from coronavirus, including Areema Nasreen, a staff nurse in the West Midlands, Thomas Harvey, a health-care assistant in east London, Prof Mohamed Sami Shousha in central London, Dr Alfa Saadu in north London, Dr Habib Zaidi in Southend, Dr Adil El Tayar in west London and Dr Amged El-Hawrani in Leicester.

Breaking point

Based on projections from Italy and Spain, Dr Roberts says health-care workers are bracing for the peak to hit in less than two weeks.

"If cases rise as quickly as they did in Spain and Italy, then quite frankly, we are screwed. All of our overspill areas will soon be full.

"The anaesthetic machines we have, which are designed to work for two to three hours at most, have been running for four to five days straight. We're already getting leaks and failures."

Also short of PPE, an intensive care nurse in Spain wears a bin bag and a protective plastic mask, donated by a local company

Extra intensive care beds, set up in several operating theatres and wards, have nearly doubled the hospital's capacity to support critically ill patients, particularly those who can't breathe for themselves and need to be put on a ventilator.

However, by expanding intensive care, Dr Roberts says it's the nursing staff who are disproportionately affected.

"Intensive care nurses are highly trained and normally deliver care one-to-one to those critically ill. Their patients may be asleep, but they have such a close relationship, they can describe every hair on a patient's head.

"But now, with these extra beds, nurses are under pressure to look after up to four patients, while delivering the same level of critical care. They are in tears and really struggling. They are the most important part of the system, but that's where it's going to fall down".

Stay at home

Outside in the hospital car park, Dr Roberts describes how a new temporary building has appeared in the ambulance bay with just one purpose - to vet all patients for symptoms of coronavirus before they are admitted.

It is run by a clinician, who, Dr Roberts points out, could otherwise be looking after patients. She describes the unit as a "lie detector".

"It's really common for people to lie about their symptoms just to get seen. People who should have stayed at home, but they come to A&E.

"So now every single patient gets vetted in the car park, to make sure those with Covid symptoms go to the right part of the hospital and don't infect everyone else, like those who've come in with a broken arm."

But for Dr Roberts, it's not just about those turning up at A&E, it's everyone.

"Most hospital staff, we are isolating ourselves when we are not at work, so as not to put other people at risk.

"But the most frustrating thing for us is to see the parks full, or Tescos even busier than usual. Please stay at home."

Illustrations by Charlie Newland

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak