Fergus Walsh: 'I was gobsmacked to test positive for coronavirus antibodies'

- Published

Antibody tests which show that you have had a Covid-19 infection will be rolled out to NHS and care staff from next week. So what happens when you test positive? Carry on as before - and I should know.

Part of the job of a medical correspondent is getting involved. That means volunteering for medical trials, tests and so on. I forget the number of times I've rolled up my sleeve to give blood to illustrate some story, or gone into an MRI scanner to image my brain. It's what we call "show and tell" in the TV trade. So when home antibody tests were first in the news I set out to show how they worked.

The tests all vary a bit in how you perform them. All you need is a drop or two of blood, which you squeeze into a hole, add a bit of chemical and then within a few minutes you get your result.

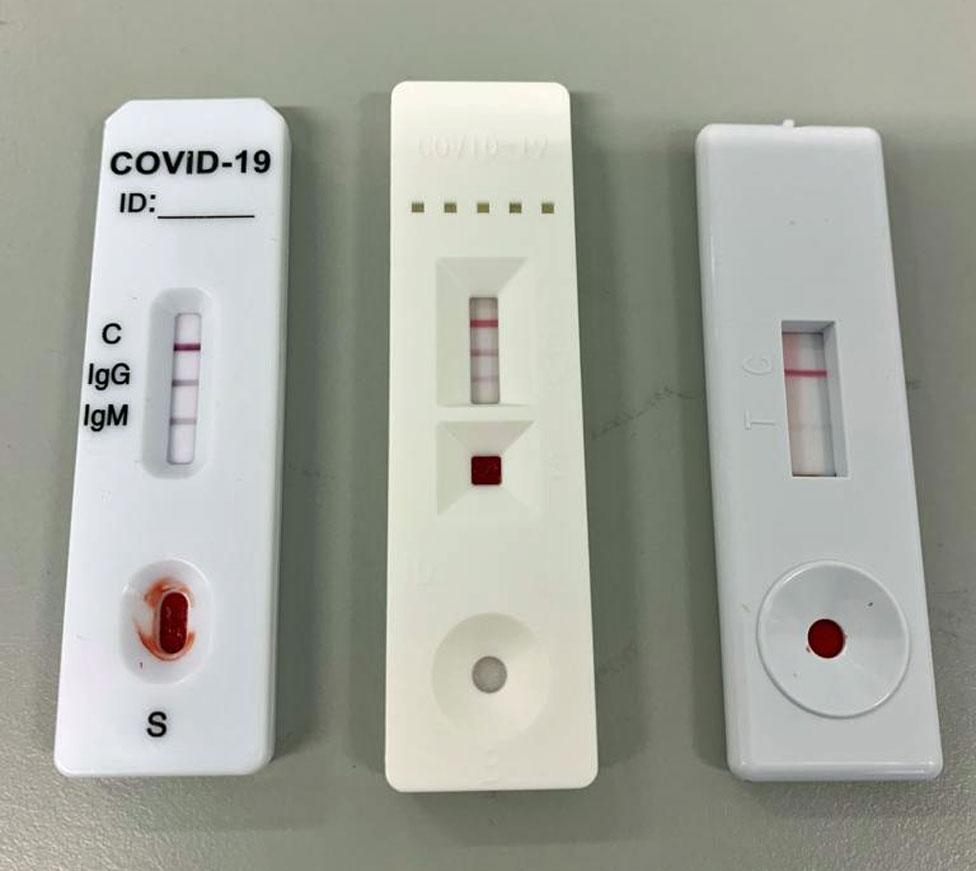

A positive result comes, as with a pregnancy test, if you get two lines across the sample window. I did the finger-prick test on camera and was surprised, and pleased, to find that I was positive for antibodies. I've since done further reports on antibody testing and had the same positive result each time. You can see the photo - excuse the blood - of three positive results, although one of them does have a faint line.

Three positive antibody tests, which gave instant results

Imperial College London are testing these finger-prick home antibody tests for accuracy and ease of use. One of the team there calculated that my repeated positive tests made it incredibly unlikely that I was continually producing a false result. In other words, it seems I have definitely had coronavirus.

Fergus on Covid

As the BBC's medical correspondent, since 2004 I have reported on global disease threats such as bird flu, swine flu, Sars and Mers - both coronaviruses - and Ebola. You could say I've been waiting much of my career for a global pandemic. And yet when Covid-19 came along, the world was not as ready as it could have been. Now it's here I wish, like everyone else, it would go away. Sadly, we may have to live with coronavirus indefinitely. In this column I will be reflecting on that new reality.

So when was this? I've not had any symptoms in recent months. I'm rarely ill, but I did have a bout of pneumonia in early January. I was off sick for about 10 days and had a cough and a high temperature. I couldn't shake it off. My GP in Windsor diagnosed a bacterial infection and gave me antibiotics. These helped a bit, but in late January I needed another course of antibiotics. These seem to have done the trick. Was it really Covid-19?

I don't think so. The first confirmed case of coronavirus in the UK was in late January when two people from China fell ill in York. It wasn't until a month later that the first cases of domestic transmission occurred. Note that although I'd been reporting on the outbreak in China by mid-January, the farthest afield I'd been in recent months was Christmas in Brussels.

So I don't think I missed a story here - the first coronavirus case in the UK was not me. But after that I've had no symptoms at all. Not a cough, not a high temperature, smell and taste normal, and no aches and pains, headaches, diarrhoea, conjunctivitis, skin rash or any of the other possible warning signs listed by the World Health Organization.

So when I pricked my finger, I had no expectation that I'd get a positive result. I was gobsmacked to be honest. The test I did showed up positive for IgG antibodies - these are the ones that form at least two weeks AFTER an infection.

I can tell you that having a positive test did not change my mindset.

I still, when I walk around, assume that everybody I meet has coronavirus, and that I have it. I don't want to infect anyone, and I don't want them to infect me.

I am still an obsessive hand-washer - having told the British public repeatedly about the importance of social distancing and hygiene, I feel I need to set an example. Every public toilet I go to involves a demonstration of what I hope is perfect hand-washing. I don't actually sing happy birthday twice out loud, but I do hum it in my head.

Early on in the UK coronavirus epidemic, there was much discussion of how antibody tests might eventually help get us out of lockdown. In March the government was talking confidently of antibody tests being a game-changer, as they would help indicate who had been previously infected with Covid-19 and therefore was protected.

Unfortunately it was not that simple.

The government bought 3.5 million finger-prick antibody tests, but when they were evaluated by scientists in Oxford, they said none of those tested was sufficiently accurate.

Things have moved on a lot since then. There are now several laboratory based antibody tests which seem fairly reliable.

Public Health England has evaluated antibody tests from Roche and Abbott. Both require a blood draw, so they are not finger-prick home tests. The sample has to be sent to a laboratory for analysis.

You can now also buy home antibody tests that you have to send to a laboratory. These are quite accurate, but you don't get an instant result.

The accuracy of a test is based on its specificity and sensitivity.

With coronavirus, you want to ensure an antibody test is highly specific so that you don't get any false positives. This could be dangerous, as it would mean some people are told they have antibodies when they don't. They might be lulled into a false sense of security, take fewer precautions to guard against infection.

Both the Roche and Abbott tests are highly specific, with near 100% accuracy. This is very reassuring. Then we come to sensitivity. This is the likelihood of a test giving a false negative. The PHE evaluation showed the Roche test to be 87% sensitive with samples taken 21 days after symptom onset while the Abbott test was 93%. This means that some people who definitely had antibodies to coronavirus may get "false negative" results. This is less important, but it is nonetheless an error.

EXERCISE: What are the guidelines on getting out?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the pandemic

RECOVERY: How long does it take to get better?

Both companies have said they can provide 10 million tests to the UK and the government has said antibody testing will be rolled out to frontline health workers from next week.

But to what end? If you have the Roche or Abbott test and get a positive result, you can be pretty confident that you have had Covid-19. This will be especially useful to anyone who did not have the up-the-nose and back-of-the-throat swab test. Remember that is for current infection, whether you have Covid-19 right now. The antibody test tells you about past infection. Furthermore you need to wait several weeks for those antibodies to show up on a test.

So that's great then. A reliable positive antibody test means you are free from lockdown, free to meet up with friends knowing you won't be infectious and are unlikely to spread the disease, right?

Not so fast. It's just not that simple.

There is no consensus on what a positive antibody test means for an individual. Some virologists I've spoken to reckon it will give you a degree of protection from coronavirus, and in particular from severe symptoms, but whether that will last for months or years is uncertain.

With Sars, antibody levels started to disappear after two or three years.

There's another complication. Current antibody tests don't distinguish between the presence of neutralising antibodies, which would clear any new infection, and non-neutralising antibodies.

We also don't know the importance of T-cell responses - another part of the immune system, which doesn't involve antibodies.

So, having antibodies to coronavirus might not be the get-out-of-lockdown pass you might have assumed.

Everyone I have spoken to has said no-one should change their behaviour based on a positive antibody test.

So what's the use of rolling out antibody tests to healthcare workers?

Firstly, it will really help build a picture of how many people in the UK have had coronavirus. Current estimates are sketchy, and range from around 17% in London to 5% elsewhere in England. That's a huge way off the 65% or thereabouts estimated to be required for herd immunity - IF it turns out that people with antibodies are indeed immune.

It will also give us the first really accurate picture of how many people have had coronavirus without knowing it, so-called asymptomatic cases - people, it seems, like me.

Follow @BBCFergusWalsh, external on Twitter

The BBC's Fergus Walsh meets medics treating patients with Covid-19 at University College Hospital London