Coronavirus doctor's diary: The drug combination that may help us beat Covid-19

- Published

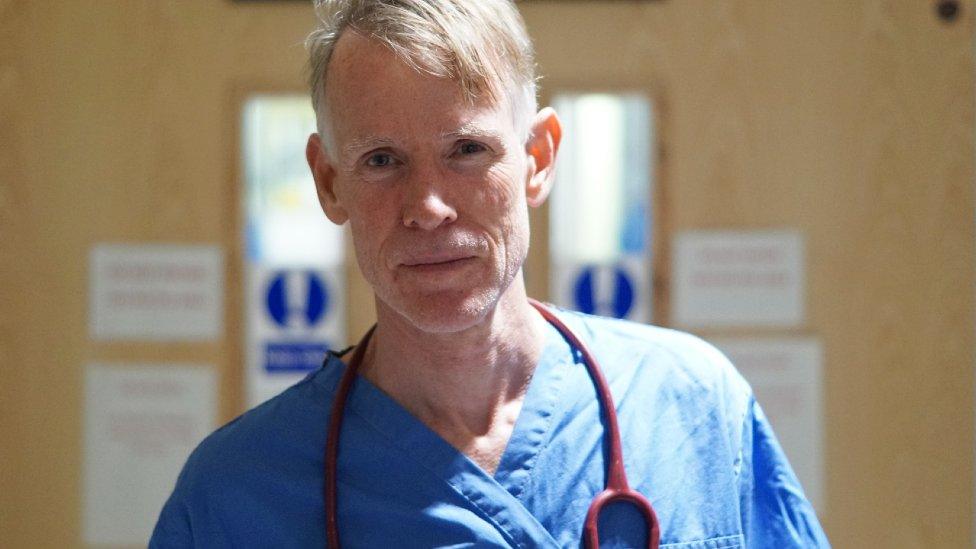

Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary (BRI) describes some of the trials under way to find a cure for Covid-19, and suggests that a combination of three different types of drug may hold the key.

At BRI we are now participating in eight different clinical trials to try and find a cure for Covid-19.

We are part of a huge international effort. It feels like all the light of global science has been concentrated into a laser beam directed at this almost invisible virus.

The biggest of the trials we are involved in is the Recovery trial. Already more than 10,000 patients have been recruited nationwide and are taking either a placebo or one of a list of four drugs. (Since I wrote about this important trial last month some recruits have begun to be randomly selected to receive a second treatment, in addition to the drug from the first list.)

Last week at BRI we also recruited the first patient in the UK for a trial to test whether a new drug made by AstraZeneca is safe and effective. This is one of a number of small trials - jointly referred to as the Accord trial - designed to assess further drugs that may be added to the Recovery trial.

The hope is that this AstraZeneca drug, which does not yet have a name, will help to damp down a dangerous overreaction of the immune system that occurs in a small proportion of patients, sending the body into shock and closing down vital organs, such as the lungs, heart, blood vessels and kidney.

This overreaction has been referred to as a "cytokine storm" - cytokines being molecules that flag up the presence of an infection that the body must fight. The drug in the new trial blocks a cytokine called IL-33 (or interleukin-33).

Mark Winterbourne (pictured here with Mo Farah) will either be given the IL-blocker or a placebo

Mark Winterbourne, who volunteered to take the IL-blocker, arrived in hospital with symptoms that were at first thought to be caused by gallstones. It was only after he tested positive for Covid-19 that we realised this was the probable source of the problem. (Covid-19 is an illness with a wide variety of symptoms - but this is an unusual case!) Mark says volunteering comes naturally to him; while working as a volunteer photographer for the Great North Run, he met and became friends with Sir Mo Farah.

I suspect that a vaccine for Covid-19 is still a year away, so these trials searching for treatments are critical.

The doctors here are looking ahead to a time - not too far off, they hope - when anyone with early symptoms will be able to drive to a testing centre, get swabbed, get a quick result and a prescription for a combination of effective drugs, before the worst of their symptoms take hold.

This combination may include an antiviral drug, an immune suppressing drug, and an anti-inflammatory drug.

Among antivirals being tested, one may help prevent the coronavirus attaching to the lining of the lungs, and another, Remdesivir, may help to stop it reproducing in the body. Remdesivir has just been approved for treating some NHS hospital patients.

Immune-suppressing drugs could help prevent the immune overreaction to the virus - the cytokine storm. If the IL-33 blocker from the Accord trial is effective, it would be a contender.

Anti-inflammatory drugs include steroids - for example Dexamethasone, one of the first drugs included in the Recovery trial.

Front line diary

Prof John Wright, a doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio.

Listen to the next episode of The NHS Front Line on BBC Sounds or the BBC World Service

Or read the previous online diary entry: A patient given hours to live who proved everyone wrong

It seems increasingly unlikely that a single drug will cure Covid-19. It's through combinations of drugs that in the past we have beaten TB - with a combination of antibiotics - and HIV - with a combination of antiretrovirals - and I expect it will be the way we beat this illness too.

BRI Respiratory consultant Dinesh Saralaya feels optimistic that a combination treatment will be available before the end of the summer.

"I think we'll find at least two or three drugs which will prevent these patients ever needing to come into hospital," he says.

"You will go to the test centre and then be given the drugs once you're diagnosed. Under the current strategies, you get the Covid virus, so you're isolating, then you get worse, you get a temperature, you start getting breathless, then you come in. But people need to be given the drugs very early."

Another of our consultants is potentially contributing to another trial - as a donor of antibodies.

Debbie Horner caught Covid-19 at a very early stage of the outbreak and quickly recovered. Two weeks ago, when a call went out for people like her to donate convalescent blood plasma, she immediately agreed.

Researchers want to find out whether antibody-rich plasma from people who have had Covid-19 will help other patients fight off the disease. This work is also part of the Recovery trial.

It's now been discovered that the patients most likely to have high levels of antibodies are men over the age of 35 who became so ill they needed hospital treatment. NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) is keen to recruit donors who have recovered from Covid-19 and who are either male, or are over 35, or were ill enough to be hospitalised.

Debbie had a mild case so it is possible that her plasma is not as rich in antibodies as the team would like. The results have yet to come in. If her plasma is wanted she will happily donate more.

"It's a bit different to taking blood normally," she says. "They take out a fraction of the blood - the plasma fraction - and then they give you back all your red cells and other bits of blood that aren't required, so essentially, it's just like getting a bit dehydrated."

A few cups of tea are enough to fix that, Debbie says.

Blood plasma is orange

Mike Murphy, professor of transfusion medicine at the University of Oxford, says this is a great opportunity to understand more about the value of plasma transfusions more generally. Plasma was collected in the late 2000s to see if it would be a way of treating people with Ebola and flu, he says.

"But by the time there were enough convalescent donors who had recovered from the infection, and were able to donate, the peak of the infection had passed, and so there was no opportunity to test the benefit of convalescent plasma. The Covid-19 pandemic is obviously different."

Follow @docjohnwright, external and radio producer @SueM1tchell, external on Twitter

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

IMPACT: What the virus does to the body

RECOVERY: How long does it take?

LOCKDOWN: How can we lift restrictions?

ENDGAME: How do we get out of this mess?