Coronavirus doctor's diary: 'People think it's over, but it's not'

- Published

Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary talks to two colleagues who have lived away from home since the early days of the pandemic to avoid the risk of infecting their families. One says she fears that cases will begin to rise because members of the public, unlike medical staff, seem too eager to "move on".

I am so humbled by the personal sacrifices that some of my colleagues have made during the pandemic. Those with young children who have sent them away to their parents to protect them from harm, like evacuees to the countryside during World War Two. Those who have retreated into lives of hermits to reduce the risk of any transmission from their work environments.

Healthcare workers are five or six times more likely to be infected than the general public, so they also have a much greater risk of infecting others. Living as a civilian in a house with a healthcare worker can be bad for your health.

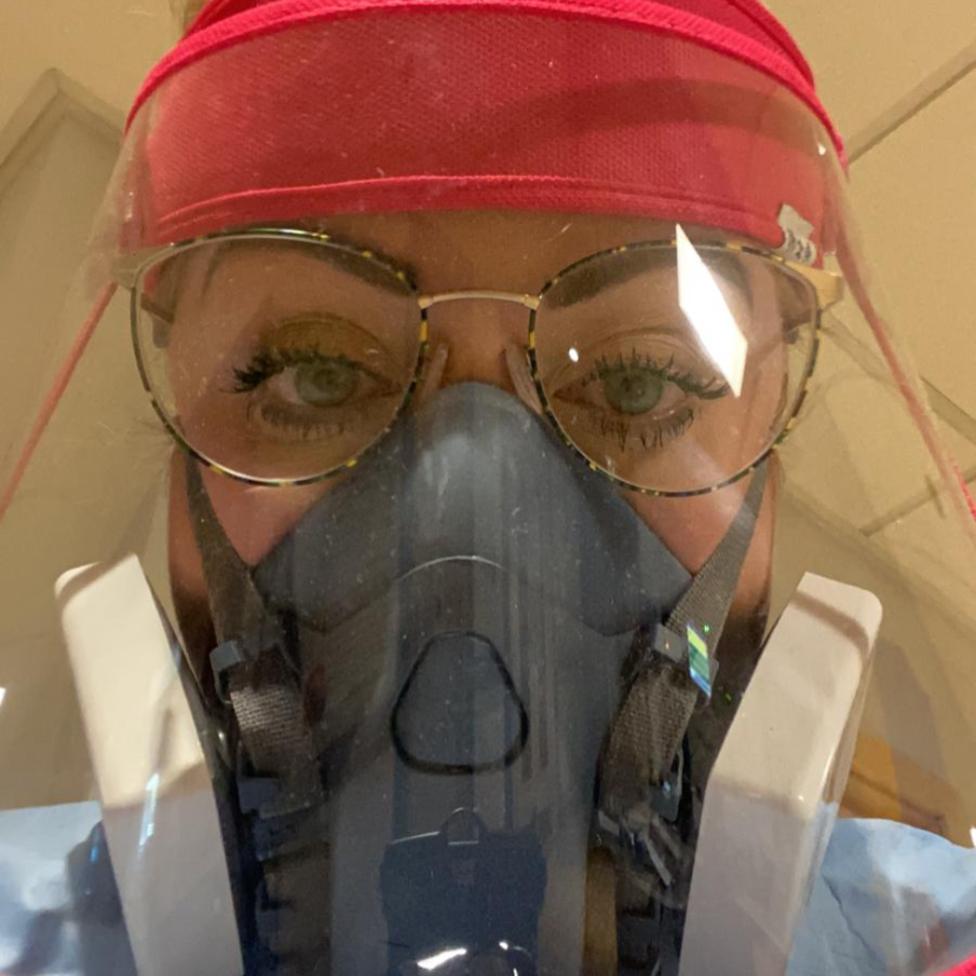

Becky Aird is a specialist respiratory nurse and acting ward sister on our busiest Covid-19 ward. Three months ago, before we had our first patient, she made the tough decision to move out of her parents' home to protect her mother, who has MS.

Kirsten Sellick is a junior doctor who moved out of a family home to live in hospital accommodation. I see her on sunny days reading outside the hospital - the car park is her lockdown garden retreat.

Becky Aird, acting ward sister

After lockdown I was offered the chance to move into the hotel to keep my family safe and I took it. That was 30 March. My mum is quite poorly, she's got secondary progressive MS, she's very independent and both she and my dad wanted me to stay at home; they kept thinking of ways we could live together safely but I knew it wouldn't be 100% safe. There was no way to eliminate the risk for my mum. The only option was to eliminate myself.

Becky Aird with her mother and a young relative, pre-lockdown

At first I thought it was quite cool in the hotel - it was like going on a little holiday - but it quickly wore off. I've got a reasonably small room. I brought a travel fridge with me and it broke within the first week. It's just very lonely, and I mostly read. I haven't seen my friends, just one girl who I dropped a care package off to and she stood at her front door.

I was very upset when one of my friends, Kelly, was admitted to my ward. I was the main nurse in charge and it really shocked me, it was such a big thing to see her fighting for breath and so ill. I was crying when I got back to the hotel - I couldn't stop thinking about her. She asked me to promise her that she wasn't going to die. Thankfully she went on to CPAP [non-invasive ventilation] and started to improve.

We are still admitting patients on to the Covid ward and I don't see much sign it's stopping. Some people tell us they haven't been social distancing - they've been with relatives, or to other houses. I definitely think it's going to get worse before it gets better, because I think people just think that it's over.

The sad fact is that there are nurses and doctors and healthcare workers struggling to work in PPE, working really hard for three months in such difficult conditions, and like me, making sacrifices - not seeing family and friends, following all the rules - and then there are people out there that aren't doing that. So that's disheartening.

It's really sad. It's funny because people did love the NHS and clapped and everything - people really cared. But then it's kind of people want to move on. I don't necessarily agree that we should be called heroes, but I think that that might have all been forgotten about now.

I'm leaving soon, because soon I'll have done three months in the hotel and the bill [paid by the NHS] is mounting up. There's nowhere else I could stay to be isolated so I need to go back home - and that means stopping work on the Covid wards.

I would stay if I could. Don't get me wrong, there have been some horrendous things, but this is what I'm trained for. I have the ability to help, to make a difference and if living in the hotel is the only way to do it, then I'm prepared for that. I don't have children. I don't have a partner. But I'm also really looking forward to being home, to having my own bed, to being with my parents again.

I will miss the Covid ward. The team's fantastic. Everyone's been so pleasant and lovely with each other, I think that's been the best thing. I've actually seen patients get better and clapping them out is my favourite thing ever. I love that.

Front line diary

Prof John Wright, a doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio.

Listen to the next episode of The NHS Front Line on BBC Sounds or the BBC World Service

Or read the previous online diary entry: The older doctors risking their lives to battle Covid-19

Kirsten Sellick, junior doctor working in intensive care

My garden is the hospital car park and my commute is dreamy - it takes me two minutes to get from my bed into work. But it's a bit odd - I don't ever leave the hospital site.

I was living with family and it made more sense not to live with them as I'm high-risk, interacting with patients who are really unwell with coronavirus. The thought of taking it home to family was just too much.

It is pretty lonely. There are two other doctors but it's difficult not being around family or people you love, and a phone call can only do so much.

I've been in the flat for months now. I had to properly isolate when my flatmate had a positive test, so we couldn't even leave the flat. That was really bad. It's a hospital flat so the window has a padlock on it and only opens less than an inch so my fresh air was leaning against the window trying to breathe in some air.

You get used to having a garden, a nice kitchen and a home but now I haven't got any of that. I have found a little bit of the car park that I sit in when the sun is out.

It's been sad work, seeing young people who aren't doing as well as I'd like them to. It's hard to explain to family members - I try to get across that we are doing our best. But it's been heart-breaking speaking to them on the phone.

It was a lovely moment to see our first patient come off the ventilator and leave the ward. That makes the sacrifice worth it - knowing we can really help people.

I'd love to be done, so that I could go and see my family and my partner, I'd really love to do that but I don't feel like I can yet. I'm hoping that time will come soon.

Becky and Kirsten are the embodiment of the dedication of the NHS front-line workers. This is what they trained for - to care for people and to save lives. However, working on the Covid "red" wards has to be one of the toughest jobs, both physically and emotionally, and I worry about the impact on their physical and mental health when they are separated from their usual support networks of loving family and friends.

We will have to work hard to care for our carers.

Follow @docjohnwright, external and radio producer @SueM1tchell, external on Twitter

40,000 DEATHS: Could they have been prevented?

FACE MASKS: When should you wear one?

EUROPE LOCKDOWN: How is it being lifted?

TWO METRES: Could less than 2m work?

VACCINE: How close are we to finding one?