Coronavirus: World reaches dangerous new phase

- Published

With the coronavirus pandemic reaching a global total of 10m cases, external, the head of the World Health Organization (WHO) has warned of a dangerous new phase in the crisis.

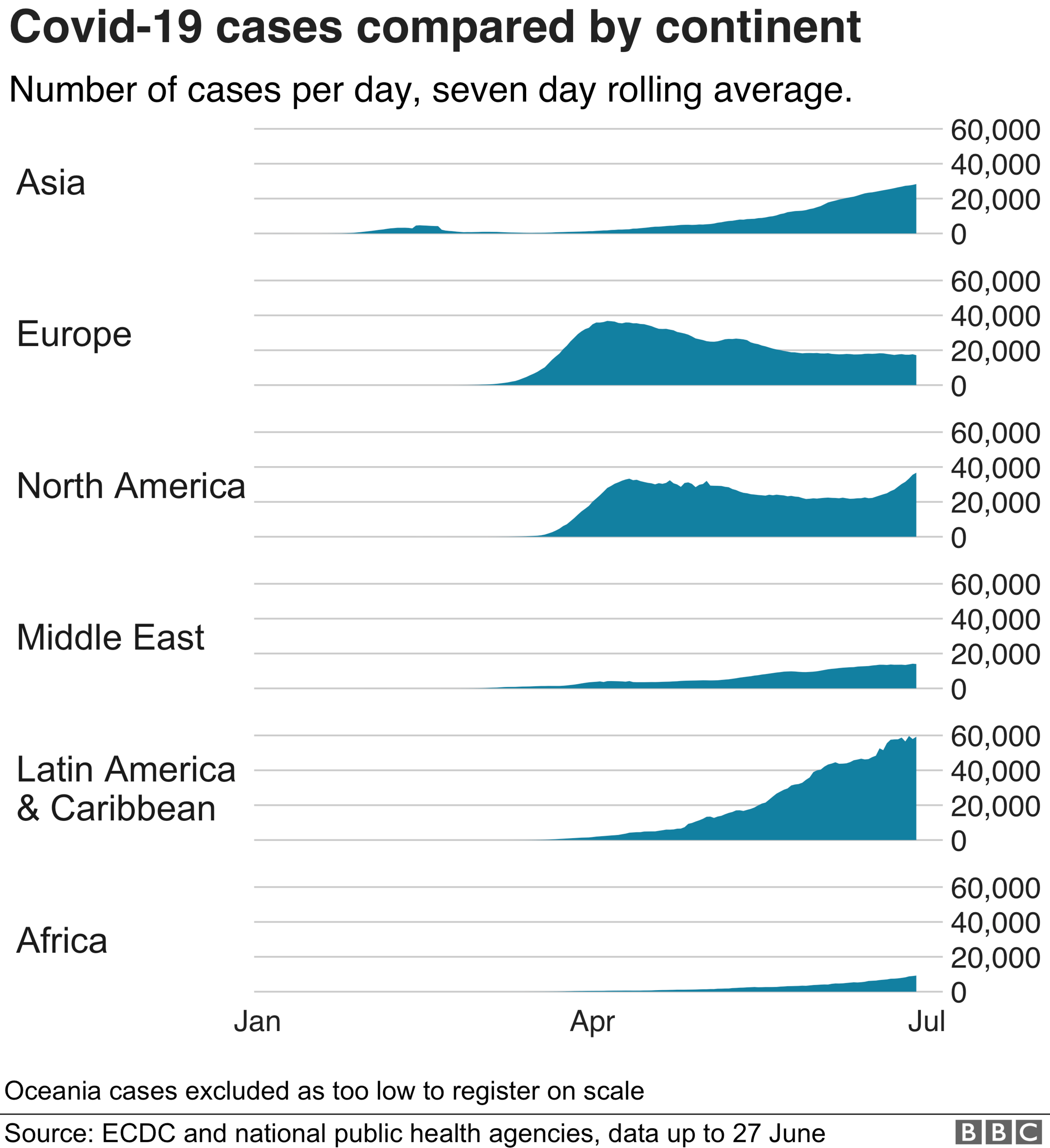

While many countries in western Europe and Asia have the virus under some degree of control, other regions of the world are now seeing the disease spread at an accelerating rate.

It took three months for the first one million people to become infected, but just eight days to clock up the most recent million.

And because these numbers only reflect who has tested positive, they're likely to be "the tip of the iceberg", according to one senior Latin American official.

Where are cases rising fast?

The graphs are moving in completely the wrong direction in parts of the Americas, south Asia and Africa.

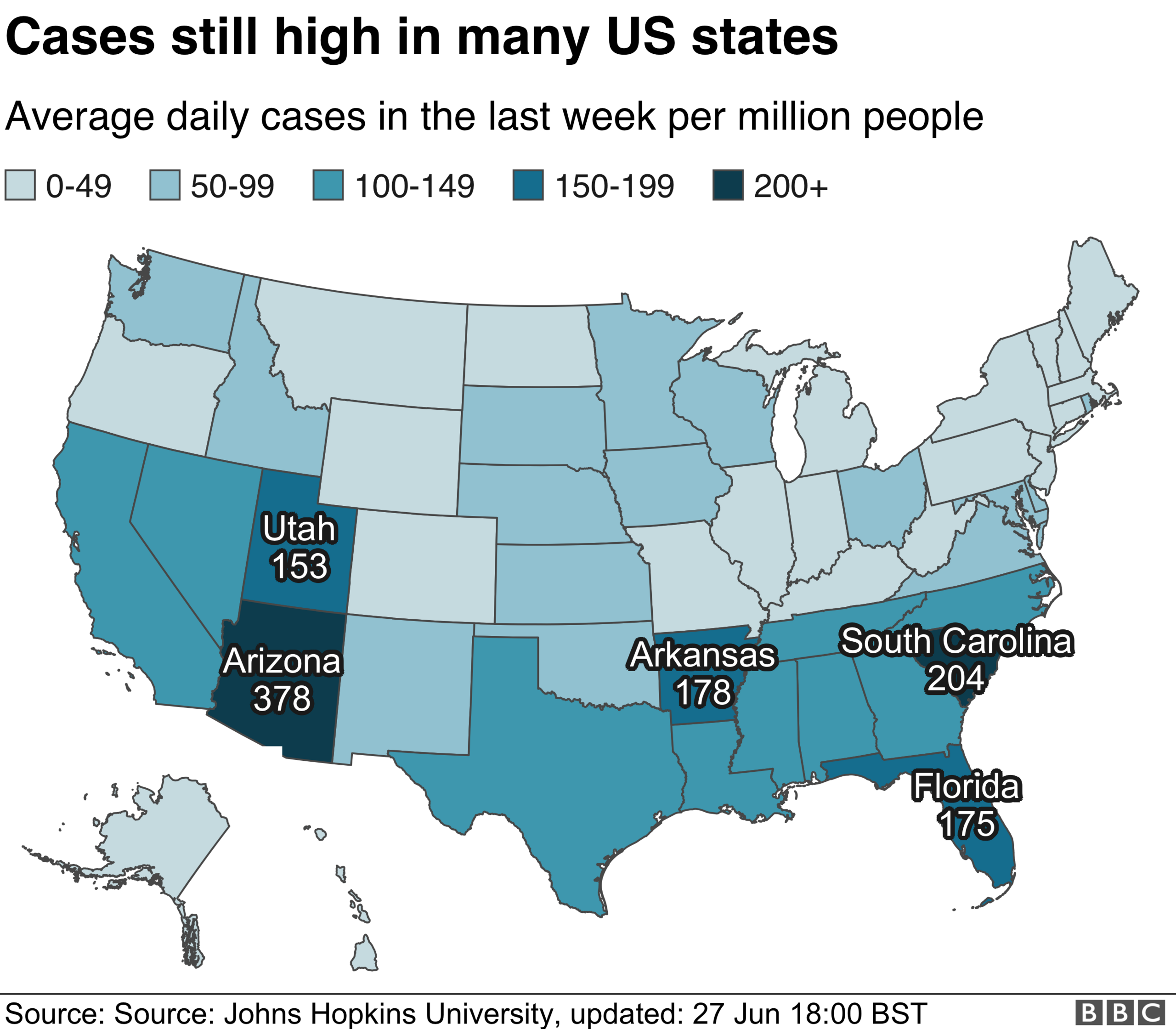

The US, already recording the most infections and most deaths from Covid-19 anywhere in the world, is seeing further startling increases. The number of positive tests recorded in the past few days has reached a daily record total of 40,000, and it's still climbing, fuelled by an explosion of clusters in Arizona, Texas and Florida.

This is not a "second wave" of infections. Instead, it's a resurgence of the disease, often in states which decided to relax their lockdown restrictions, arguably too early.

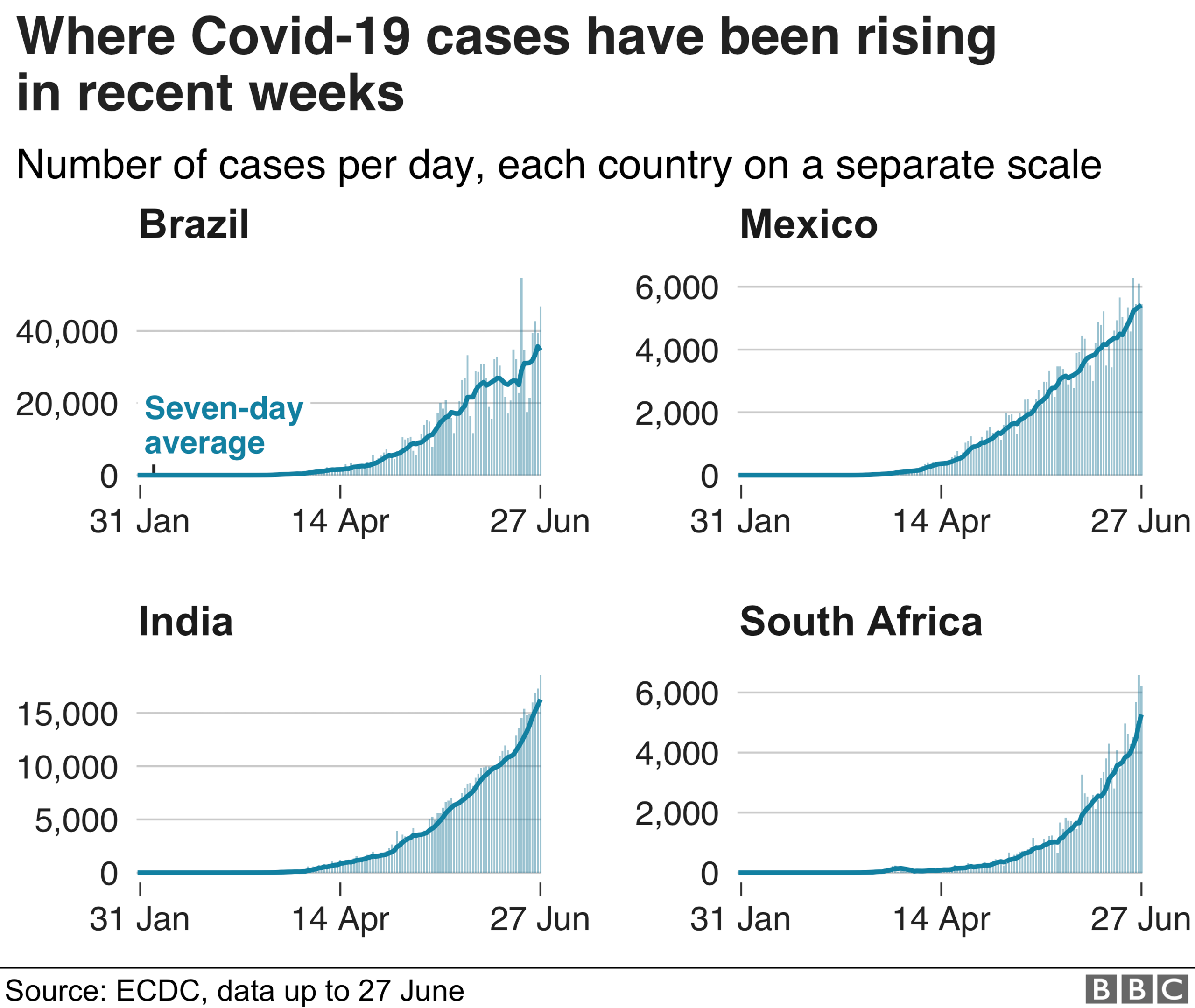

Brazil, the second country after the US to pass 1m cases, is also experiencing dangerous rises. Its biggest cities, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, are the hardest hit but many other areas of the country are doing little testing, and the real numbers are bound to be far higher.

Something similar is happening in India. It recently recorded its greatest number of new cases on a single day - 15,000. But because there's relatively little testing in some of the most heavily populated states, the true scale of the crisis is inevitably larger.

Why is this happening? Deprived and crowded communities in developing countries are vulnerable. Coronavirus has become "a disease of poor people", according to David Nabarro, the WHO's special envoy for Covid-19.

When whole families are crammed into single-room homes, social distancing is impossible, and without running water, regular hand-washing isn't easy. Where people have to earn a living day-by-day to survive, interactions on streets and in markets are unavoidable.

For indigenous groups in the Amazon rainforest and other remote areas, healthcare can be limited or even non-existent.

GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the coronavirus pandemic

EUROPE: How are lockdowns being lifted?

TRACKER: Coronavirus cases in Africa

UNITED STATES: How the Najavo Nation is battling America's worst outbreak

And the rate of infection itself is often worryingly high: of everyone tested in Mexico, just over half are turning out to be positive. That's a far higher proportion than was found in hotspots like New York City or northern Italy even at their worst moments.

Shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) for frontline medical staff are far more severe where budgets are small.

In Ecuador, where at one stage bodies were being dumped in the streets because the authorities could not cope, a key laboratory ran out of the chemicals needed to test for coronavirus.

And where economies are already weak, imposing a lockdown to curb the virus potentially carries far greater risks than in a developed nation.

Dr Nabarro says there is a still a chance to slow the spread of infections but only with urgent international support. "I don't like giving a depressing message," he says, "but I am worried about supplies and finance getting through to those who need them."

The political angle

But these are not the only things driving the rise. Many politicians have chosen for their own reasons not to follow the advice of their health experts.

The president of Tanzania took the bold step of declaring that his country had largely defeated the virus. Since early May he has blocked the release of proper data about it, though the signs are that Covid-19 is still very much a threat.

In the US, President Trump has either played down the disease or blamed China and the WHO for it, and urged a rapid re-opening of the American economy.

He praised the Republican governor of Texas, Greg Abbott, for being among the first to bring his state out of lockdown, a move now being reversed as cases rise.

Even the wearing of masks in public, which has been an official US government recommendation since early April, has become a symbol of political division.

Mr Abbott has refused to allow Texan mayors to insist on them so that, as he put it, "individual liberty is not infringed". By contrast the governor of California, a Democrat, says the "science shows that face coverings and masks work". Mr Trump, meanwhile, has refused to wear one.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, has been caught up in the same kind of argument. Having dismissed the coronavirus as "a little cold", he's repeatedly tried to stop officials from doing anything that might disrupt the economy. And after regularly appearing in public without a mask, he's now been ordered by a court to wear one.

It's attitudes like this that prompted the head of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, to warn that the greatest threat is not the virus itself but "the lack of global solidarity and global leadership".

Where are cases under control?

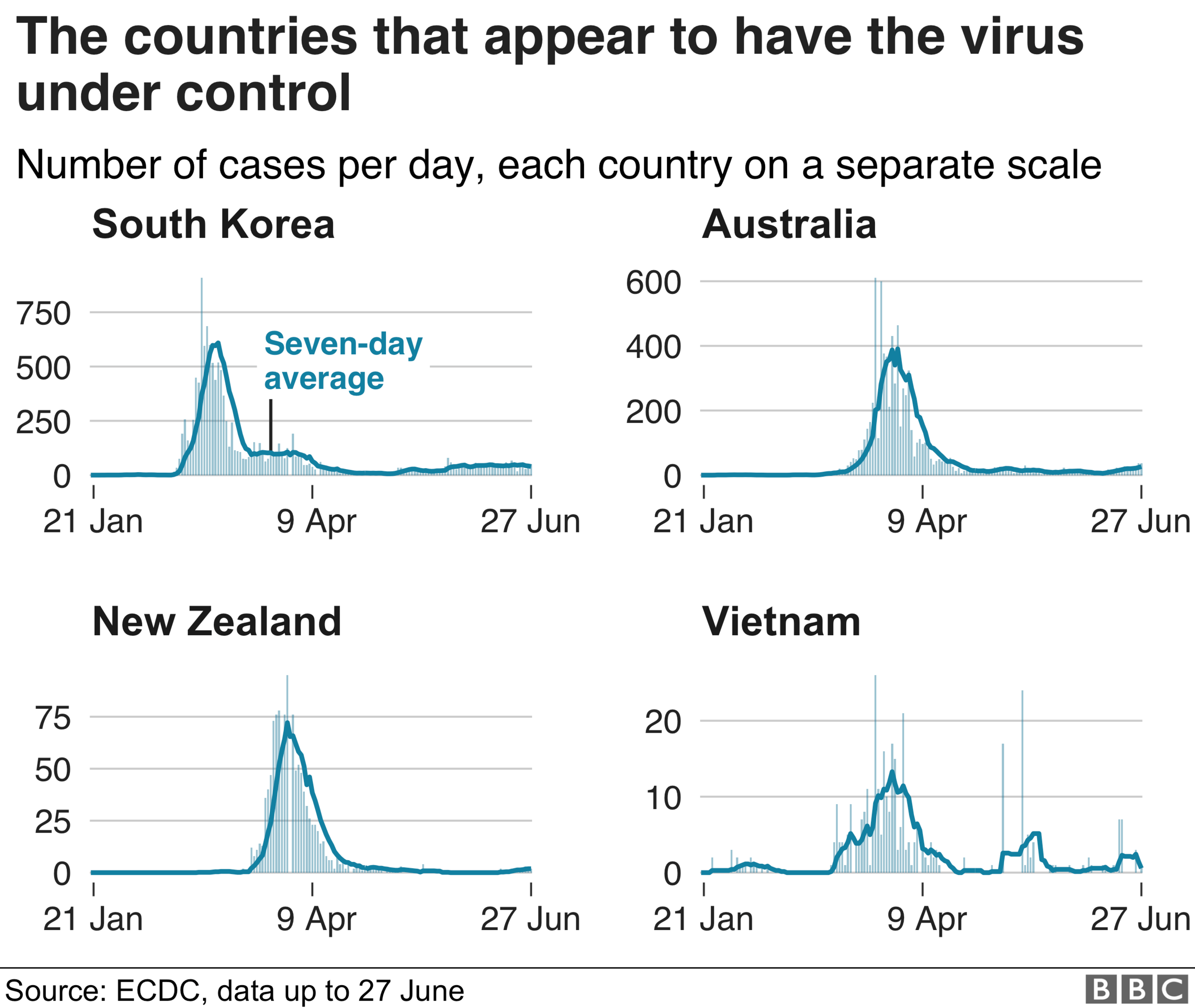

As a remote set of islands in the Pacific, New Zealand is able to isolate easily, and the government of Jacinda Ardern has been widely praised for an aggressive response which recently led to a 24-day period with no new cases.

That came to an end as citizens started to return from abroad, some of them infected, and further measures have been needed to monitor people on arrival. But rather than this being a blow to New Zealand's hopes of becoming Covid-free, many experts see it as evidence of a surveillance system that generally works effectively.

Similarly, South Korea is lauded for using technology and contact tracing to drive down infections to extremely low numbers and had three days in a row with no new cases.

Its officials now say they are seeing a second wave, with clusters centred on nightclubs in the capital Seoul, though the numbers are relatively small.

The mayor of Seoul has warned that if cases go above 30 for three days, social distancing measures will be re-imposed. By contrast, the UK has roughly 1,000 new cases a day.

Proudest of all is Vietnam, which claims to have had no deaths from Covid-19 at all. A rapid lockdown and strict border controls combined to keep the numbers of infections low.

What's next? A big unknown is what happens in most of the countries of Africa, which in many cases have not seen the scale of disease than some feared.

One view is that a lack of infrastructure for mass testing is obscuring the true spread of the virus. Another is that with relatively young populations, the numbers becoming afflicted are likely to be lower.

A third perspective is that communities with fewer connections to the outside world will be among the last to be touched by the pandemic.

In countries that have most successfully controlled the virus, the challenge is remaining vigilant while trying to allow some normality to resume.

But the reality for many of the rest is Dr Nabarro's grim forecast of "continued increases in the numbers of people with coronavirus and the associated suffering".

Which is why he and many others are hoping that developing countries will get the help they need, before the crisis escalates any further.