Coronavirus: Is the UK in a better position than we think?

- Published

Another day, another worrying coronavirus headline.

On Tuesday it was reported the UK's testing and tracing system was not good enough to prevent a second wave once schools reopen.

It came after Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced last week the brakes were being applied on the lifting of further restrictions.

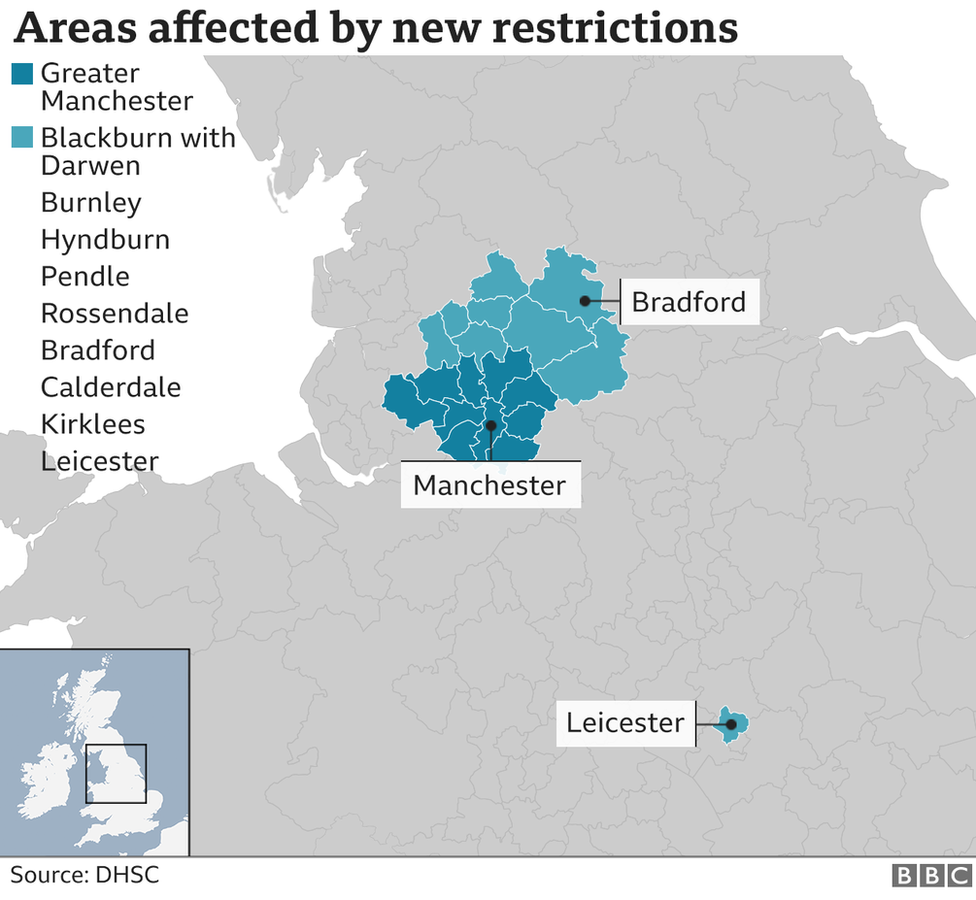

And that was off the back of the announcement that parts of northern England were to have some of the lockdown restrictions reimposed on them.

The problem, ministers and their advisers warned, was that infections were on the rise.

We had, concluded chief medical adviser Prof Chris Whitty, reached the limits of lifting lockdown.

It prompted a weekend of debate, with people urging pubs to close so schools could open.

But is the situation really as bad as it seems?

Infection rates 'not rising in any significant sense'

It was one of the more curious aspects of last week's warnings that the government seemed so ready to embrace the concept that infection rates were on the up.

This is a government that all along the way has been trying to mount a vigorous defence of its record.

The surveillance programme - run by the Office for National Statistics - did suggest they were rising.

But there have to be heavy caveats around these findings - they are based on just 24 positive cases among nearly 30,000 people over the course of two weeks. Drawing conclusions from such smaller numbers is fraught with difficulties.

The other key source of data - the cases found by testing - shows numbers have started going up. They are now more than 40% higher than they were in the second week of July on a rolling-seven day average.

But that masks the fact the number of tests being carried out is increasing and being targeted at areas where infection rates are highest.

If you test more, you are likely to find more.

So if you look at the percentage of tests that are positive, the rise is marginal once you iron out the daily fluctuations.

This is a point made by Prof Carl Heneghan, who heads the centre for evidence-based medicine at Oxford University.

He says it is essential to adjust for tests being done and is concerned about what he calls "poor interpretation" of data.

Covid cases, he says, simply aren't rising in any meaningful sense.

And even if you just look at the raw number of positive tests, it is worth remembering that the figures seen are way way below what was happening during the peak when an estimated 100,000 infections a day were being seen.

Test-and-trace is not perfect, but it's achieving something

A source of much criticism recently has been NHS Test and Trace.

It is the system that has been set up in England to trace the close contacts of those who are infected to encourage them to self-isolate.

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have their own systems.

NHS Test and Trace employs more than 20,000 call handlers and contact tracers.

Swab tests are used to look for the presence of the virus

A figure often quoted in recent weeks to highlight its failings is the fact it fails to reach nearly half of contacts.

This certainly seems to be poor, but once you include the so-called complex cases passed on to local teams, incorporating council staff and regional Public Health England teams, performance rises to over three-quarters.

That is not far off what government experts said was needed to make the system effective.

What is more, the irony with the term "complex cases" is that they are actually often easier to contact because they are the ones based in prisons, care homes and schools.

The term complex refers to the fact that they represent potential clusters that will require more containing than simply asking an individual to isolate, which is what the national team does.

This is not to say the service should be above criticism.

Local directors of public health have been understandably annoyed that they have not always been given enough data quickly enough (it was only recently that they started getting postcode-level data on positive tests, allowing them to target their efforts at neighbourhood level).

But most people agree it is unrealistic to expect a service that was put together in a matter of weeks to be perfect from day one despite the prime minister's promise of a "world-beating" service (the issue of whether the UK should have been better prepared is another debate altogether).

Don't forget the public has a role to play

What is more, the biggest gain, in terms of containing the virus, would be if more people with symptoms came forward.

The ONS programme shows there are likely to be many people who are not getting a test when they are infected.

Last week data suggested perhaps only a fifth of new cases were being diagnosed.

Some will not have symptoms - and therefore not know they need to come forward for a test. But others no doubt will.

NHS Test and Trace can certainly do more to engage people - its boss, Baroness Dido Harding, has admitted as much herself.

But part of it comes down to the people.

It is a message made consistently by Nottingham University infectious disease expert Prof Keith Neal.

The government, he says, "can't do everything".

Local crackdowns are a sign of strength - we are acting early

Another tendency in recent weeks has been to view the need for local action as a sign of failure.

First Leicester was placed into local lockdown and then restrictions were introduced in other areas before last week's announcement that vast swathes of northern England were - to quote some headlines - "back in lockdown".

It gives the impression the infection is raging in these areas when what is really happening - with the exception of Leicester - is that action is being taken early to prevent the virus spiralling out of control.

Blackburn currently has the highest level of infection by some way, but even there, fewer than one in 1,000 people has contracted the virus over the past week.

The steps taken in northern England were targeted - households have been discouraged from mixing - but shops, restaurants and bars remain open.

Again, this does not mean questions should not be asked. When lockdown restrictions started being lifted in May senior officials in the north west questioned whether it was too soon for the region, which looked to be a few weeks behind where the south east was in terms of progression of the epidemic.

But all too often these nuances get lost in the frenzied debate that takes place.

Complex issues get reduced to soundbites. People want to look for someone to blame.

But what if we take a step back?

In an interview with the BBC on Tuesday, the World Health Organization's special envoy on Covid, David Nabarro, gave a very different perspective from the one we are used to.

He said there will of course be a "post-mortem" (it goes without saying mistakes have been made).

But he was also full of hope, saying he thinks the UK is "going to do really well".

Why? He said it was showing the country was able to identify where the virus was, and he could see signs that different parts of society were "pulling together and saying 'we are going to get on top of this'."

Maybe things are not quite as bad as they sometimes seem.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

- Published28 July 2020