As summer ends, UK must square up to Covid again

- Published

- comments

It is crunch time for coronavirus in the UK.

Children are returning to school and, with summer over, the return of colder weather and dark nights means more time will be spent indoors, giving the virus a better chance of spreading.

So how strong a position are we in to fight the virus?

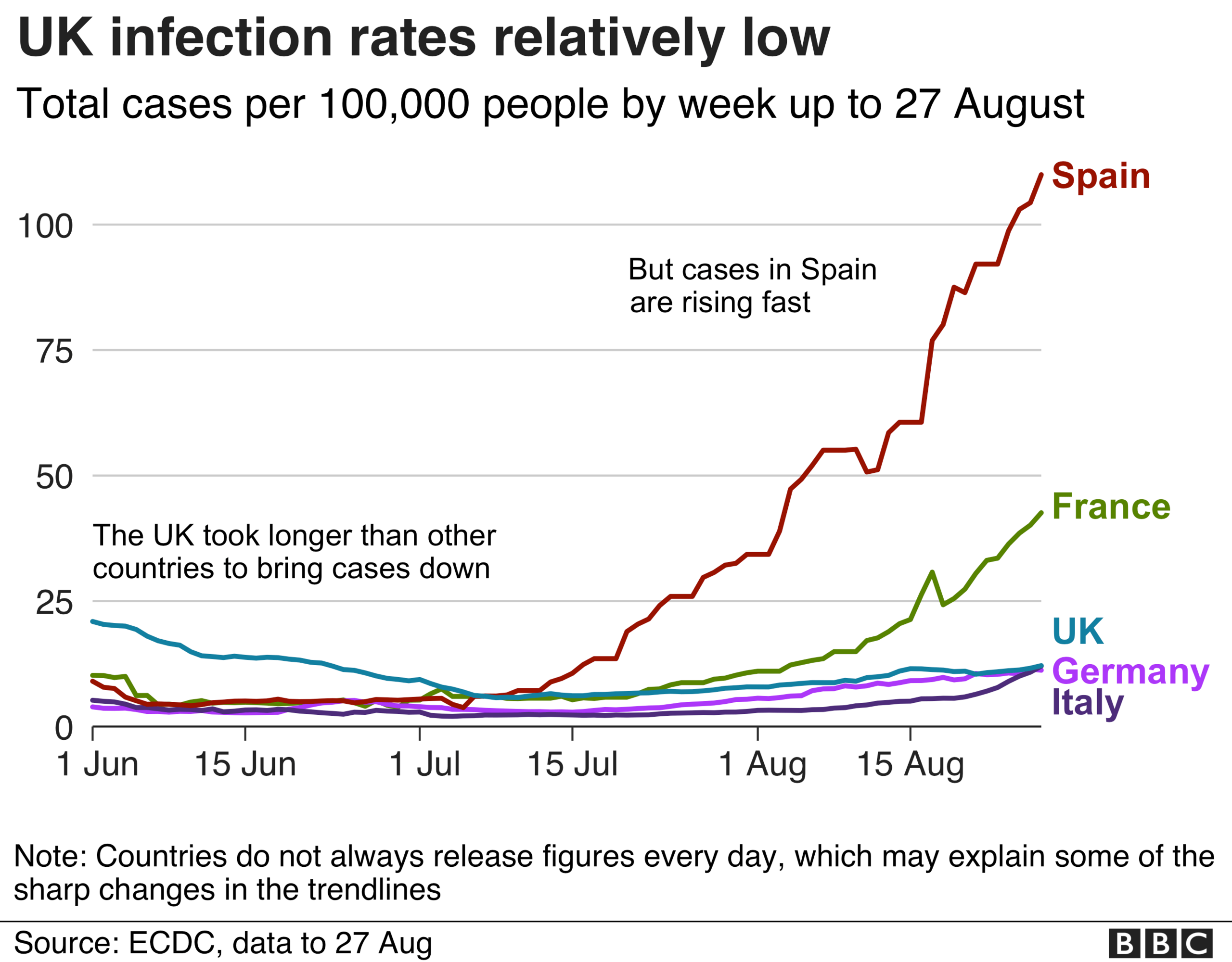

Infection rates are low

There was a point at which the UK appeared to be among the worst-hit countries in the pandemic - a review by the Office for National Statistics found that by the middle of June, the UK had the highest level of excess deaths.

But if you make international comparisons now, the UK is performing remarkably well.

This is despite much being made of the rise in cases since early July.

Daily case numbers have risen from just above 500, on average, to over 1,300 - although some of that is down to more testing being put in place.

But the numbers also need to be seen in context.

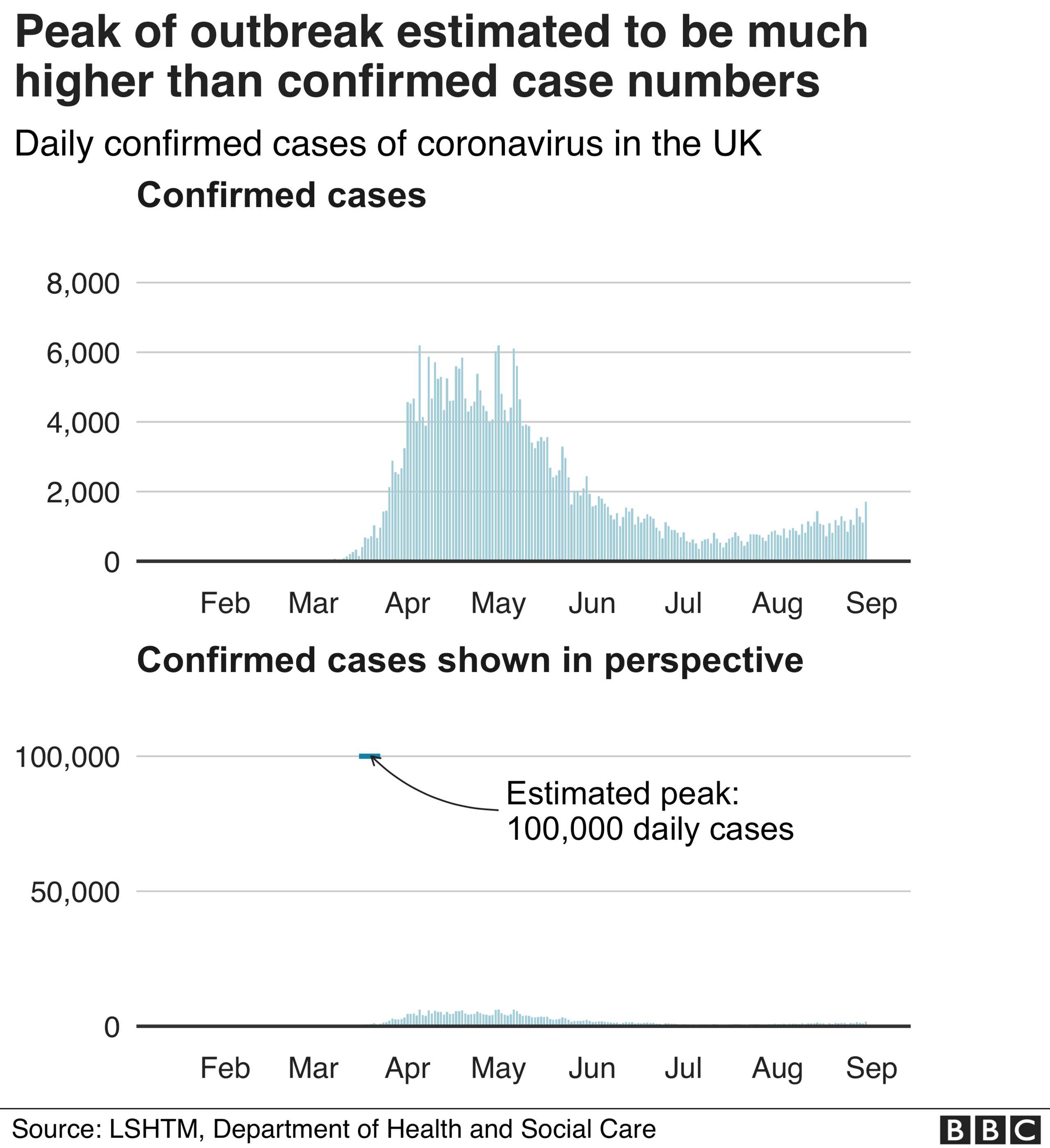

Because of the lack of testing available in the spring, it is unclear exactly how many cases there were when coronavirus was at its peak in the UK.

There were days when confirmed cases hit 6,000. But that was just the tip of the iceberg.

It has since been estimated there were perhaps as many as 100,000 infections a day at the end of March.

Of course, the system is still not detecting all the cases even with the extra testing in place.

The Office for National Statistics surveillance programme suggests the true level of infection may be about twice what is being recorded currently. But that's still a fraction of the cases seen in the spring.

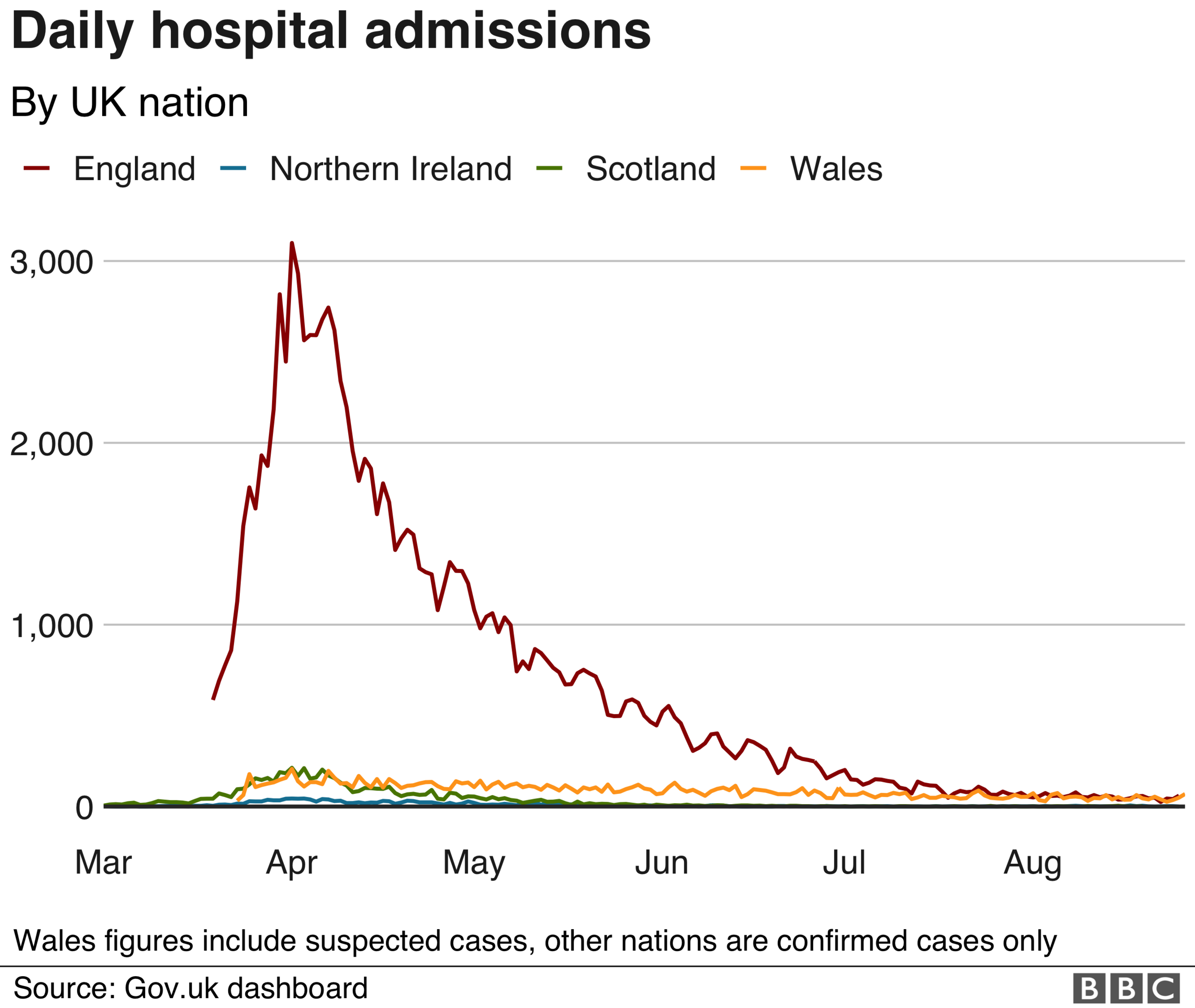

Fewer people admitted to hospital

And while there is evidence of cases increasing, that has not translated into an increase in people being admitted to hospital.

Deaths are also low - down to under 10 a day on average.

There is no guarantee it will stay like this, of course.

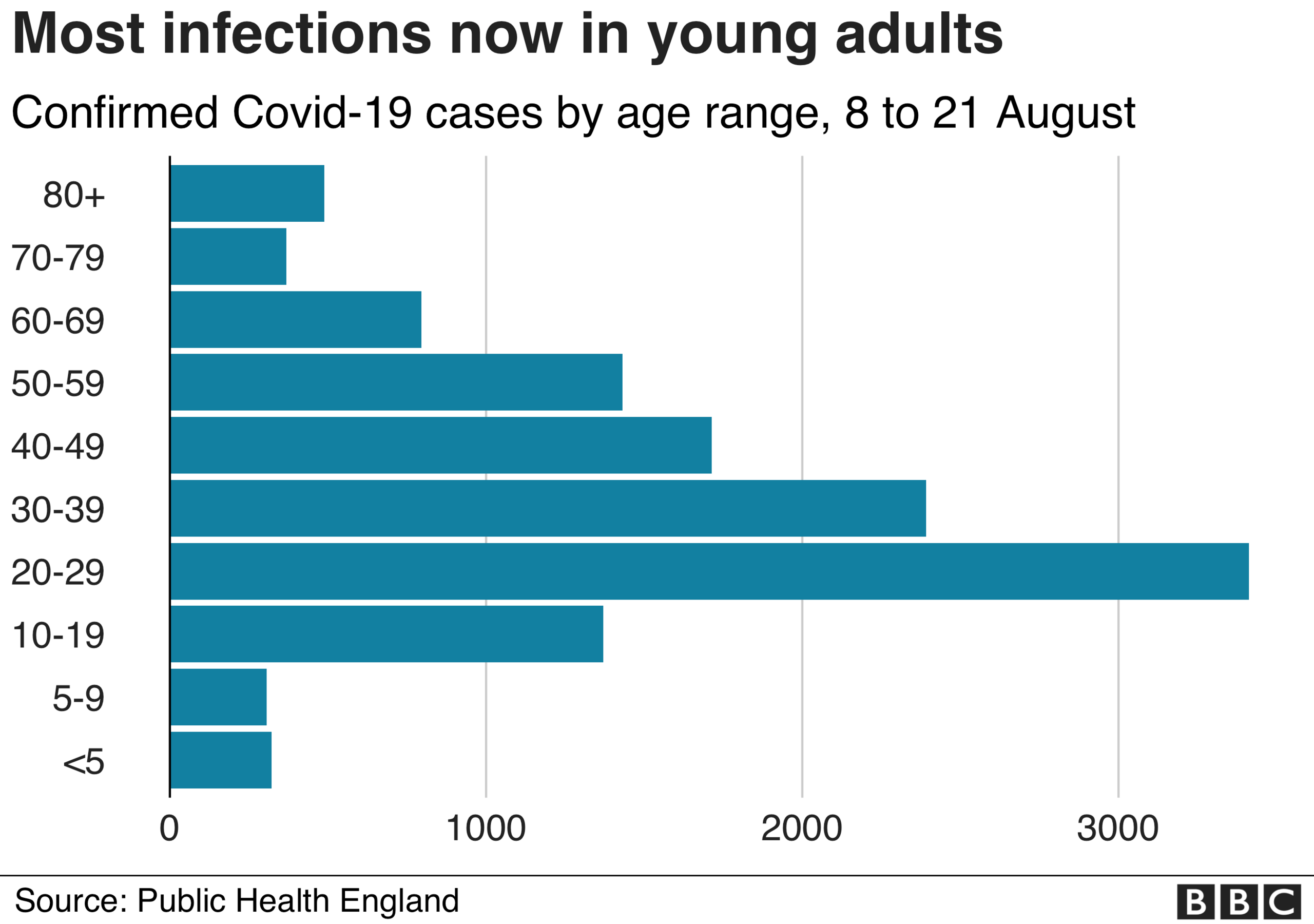

Many of the new cases are being seen in young adults who are now out more, either working or socialising.

They are at very low risk of complications so this may not seem too concerning - after all, society has to function - but the fear remains that this could lead to the frail and vulnerable catching the virus.

That said, those who fall into the more vulnerable groups will naturally be taking more precautions.

But the problem, says Edinburgh University infectious diseases expert Prof Mark Woolhouse, comes if the levels of infection rise substantially from the level being seen at the moment.

"Spillover into the high-risk population could become very hard to avoid."

A vaccine is not going to rescue us... yet

The international effort to find a vaccine is unprecedented.

There are about 150 initiatives in development, including more than 20 that have begun human trials.

One of the most promising is being developed by Oxford University - and early results suggest it can trigger an immune response.

A deal has been signed to supply 100 million doses in the UK alone.

But even with the rapid progress that is being made, a vaccine is very unlikely to be available until the middle of next year at the earliest.

And there are, of course, no guarantees it will work or just how long the protection it offers us will last.

Leading immunologist Prof Sir John Bell, of the University of Oxford, believes the likeliest scenario will be a vaccine like the one for flu that offers some protection for a limited period.

A smallpox scenario whereby a jab can wipe out the disease is only considered to be a remote possibility.

But doctors have learnt how to save more lives

Real progress has been made in the past few months on how best to treat patients who fall seriously ill with coronavirus - for the overwhelming majority it only causes a mild illness.

A cheap and widely available, low-dose steroid treatment - dexamethasone - has been found to reduce the risk of death in seriously ill patients (those who require intensive care) by a third and is now being routinely used on the front line.

It was research carried out in the UK that helped to make this breakthrough, which came in June.

Since then trials have found another steroid, hydrocortisone, is equally effective.

Other breakthroughs will no doubt come.

Different treatments are being tested on patients around the world, including the use of blood plasma from people who have been infected and recovered from the virus.

Can the virus be contained in the meantime?

It is going to be a major challenge.

The virus is stealthy. It can be passed on before symptoms develop and, significantly, some people never even know they are infectious. This is what makes it so difficult to contain.

Infections are almost certainly going to rise. But the key question is by how much and among which groups.

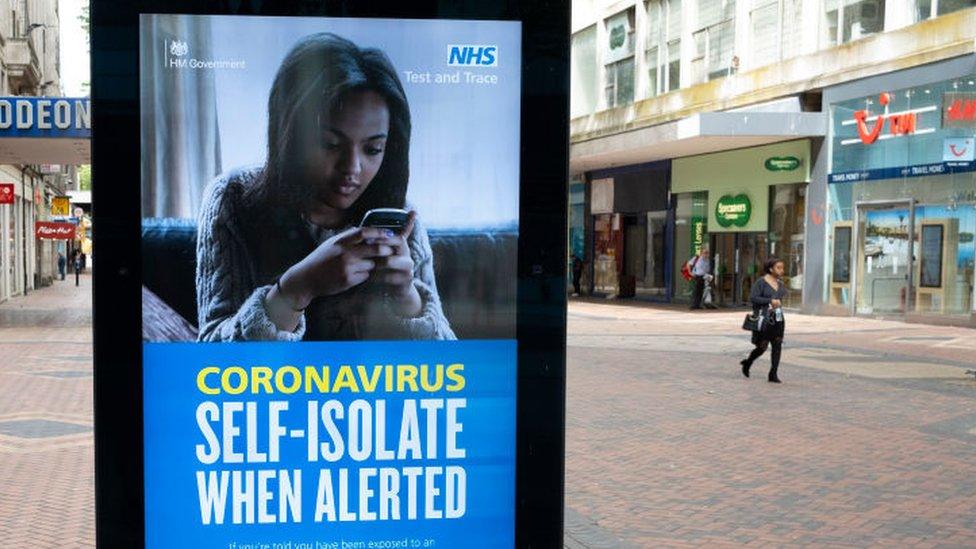

Crucial to the success will be the testing and tracing regime.

Each UK nation runs its own contact tracing system, but they work on the same principles - the details of positive cases are passed on to contact tracers who then try to identify their close contacts and ask them to isolate.

Huge strides have been made to set up an effective system. The UK is now carrying out more tests per head of population than Spain, France and Germany.

But problems still remain. A backlog has developed in processing tests at the three mega labs, which means it is taking longer to give people results - the average turnaround time is now more than 24 hours. The problems have prompted testing to be prioritised in high infection areas, meaning in some areas people are struggling to book tests at local centres.

And demand continues to grow all the time. Scotland saw a big rise in tests being requested for children after schools went back in August.

Contact tracing is also still a work in progress. England's service, for example, is still not quite reaching the 80% of positive cases and close contacts it is aiming to - although it is not that far short.

But for all the difficulties that remain, the pattern of infections, the infrastructure now in place and the improvement in treatment all do offer hope.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

- Published28 July 2020