Coronavirus: New figures show UK faces 'impossible balancing act'

- Published

- comments

The daily confirmed figures for coronavirus cases have shown a significant jump in the past two days.

On Sunday they rose by nearly 3,000 and then on Monday by almost exactly the same again - the highest single day increases since May.

It means the UK is now seeing four times as many cases on average as it was in mid July.

And with the impact of the return of schools still to come - not to mention the re-opening of universities next month - fears are growing that cases and then deaths could start spiralling.

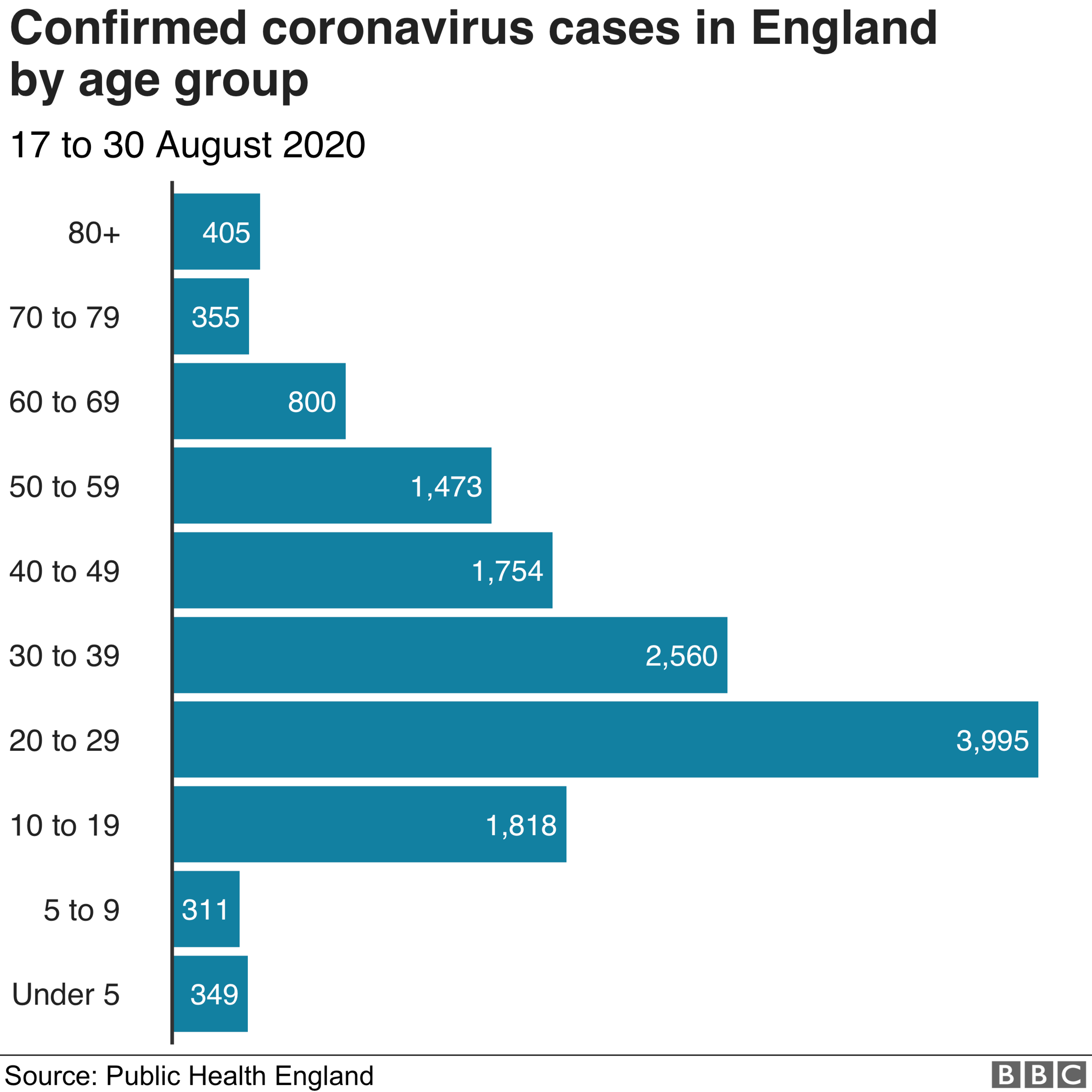

Are young people to blame?

The rise has been laid firmly at the door of young people. Around half of new cases in recent weeks have been diagnosed in people in their 20s and 30s.

Significant numbers of cases have also been identified in people in their 40s and 50s, as well as teenagers.

That compares to the early days when most of the confirmed cases were in the older age groups.

But that was because the UK was largely only testing in hospitals. Younger adults are very unlikely to be sick enough to need hospital treatment, so they hardly showed up in the official figures.

If you look at results from antibody testing, to see if they had been exposed to the virus, the younger age groups were just as likely as older groups - if not more - to have been exposed.

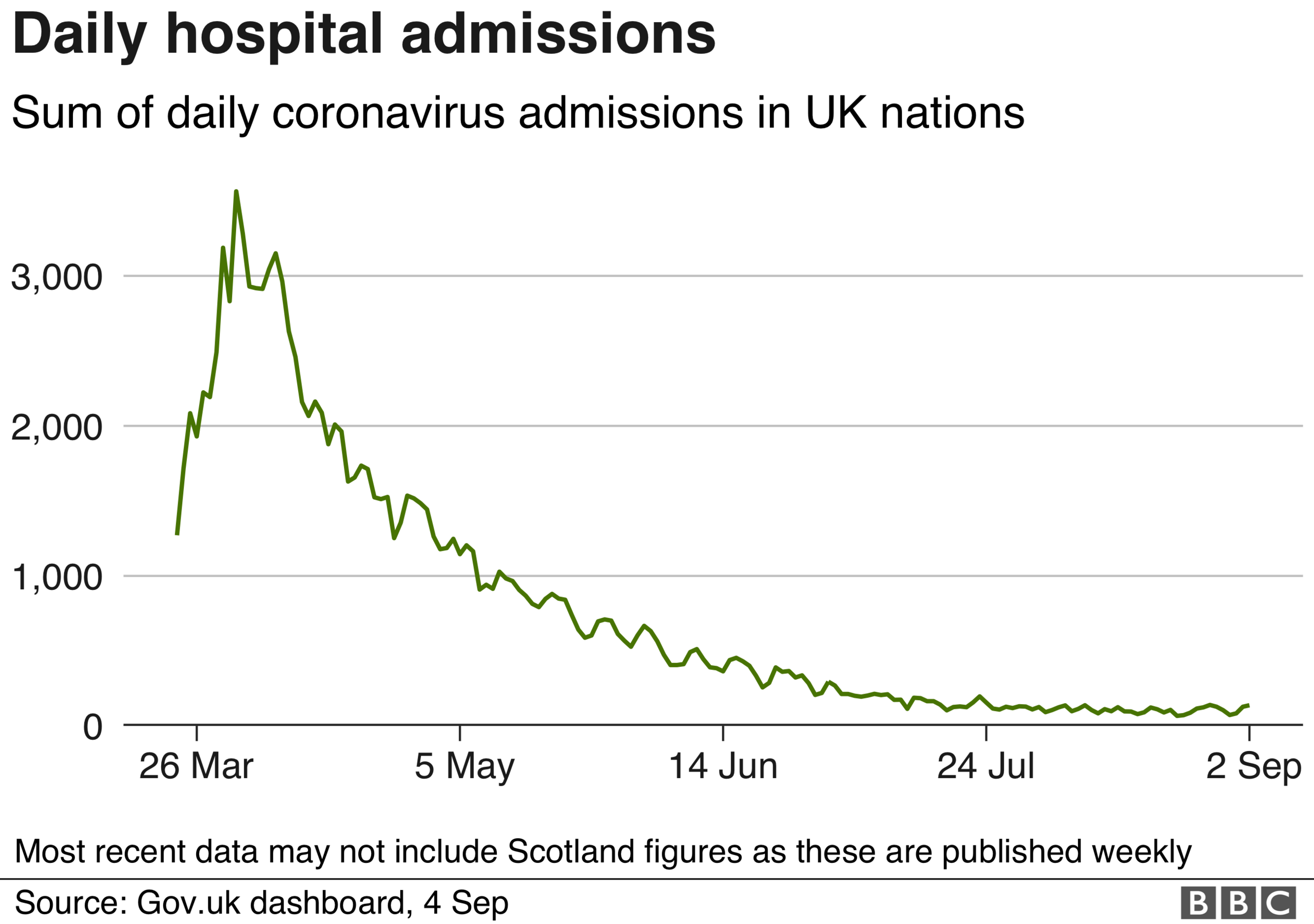

So what is happening now appears to be simply a case of the virus re-establishing itself in a group that is the least at risk of serious complications, hence there are no signs of a significant increase in hospitalisations.

Much has been made of the fact these are the groups going out socialising, although it is also noticeable that the highest rates are spread across much of the working age population - many of whom will have to leave their home to make a living.

Infection rates still at low levels

So does it matter? After all, the level of cases being seen - even taking into account there will still be some not being picked up - is well below where it was in the spring.

At the peak at the end of March, there were an estimated 100,000 cases a day (the official figures only show a fraction of these because of the problem mentioned above - testing was more or less limited to hospitals).

And the fact that cases are rising after hitting such a low mark over the summer should not come as a surprise.

More people are being tested and that testing is being targeted at high infection rate areas for one thing. But that does not tell the whole story.

With people mixing more, and summer over (respiratory viruses tend to do better because of colder weather and the fact people are indoors) cases were always going to go up, and are likely to continue to do so.

If you could keep the infections in younger age groups, who are not at any significant risk of complications, there would in theory not be much of a problem.

The difficulty, says Prof Devi Sridhar, a public health expert at Edinburgh University, is that as cases rise, this becomes harder to achieve.

She believes we are already in a position where protecting vulnerable groups will become impossible.

But she admits ministers are in a "lose-lose" situation. If they let the virus spread they will be held culpable for rising deaths, and if they re-introduce restrictions they will be criticised for over-reacting.

The result is that the UK, like all nations, faces an almost impossible balancing act - accepting some level of deaths, while keeping society functioning.

Prof Paul Hunter, an expert in health protection at the University of East Anglia, says it is not realistic to return to national lockdown, saying it would not be fair to "handicap" children any more by closing schools.

"This is a virus that is mainly risky to older, more vulnerable groups. We need to accept winter will be extremely difficult.

"It is about finding a tolerable solution. I don't think we will see the scale of deaths we saw in spring.

"But there are, sadly, going to be many this winter. It will be the worst winter for a long time."

How do we protect the vulnerable?

The key in the coming months, Prof Hunter and others believe, will be keeping deaths as low as possible by protecting the most vulnerable - more than nine in 10 deaths have happened in the over 65s with half in the over 85s.

There are a number of factors that will have an impact - and on many the UK is in a stronger position than it was six months ago.

The discovery that two steroids - dexamethasone and hydrocortisone - can reduce deaths among the seriously ill will make a significant difference.

And, as always, good hand hygiene and continued adherence to social distancing and isolating when you have symptoms will be important principles for everyone to follow.

Big local outbreaks will also need to be contained as best as possible. This is where the test and trace system comes in.

While huge progress has been made in recent months though, there are still issues to be resolved on both the availability of testing and ability to reach the close contacts of infected individuals.

On top of that, the government and care industry will have to do a better job of protecting care homes.

There is much better availability of PPE now than there was in the early days and although regular testing of staff and residents has been slow to roll out it is a world away from the situation earlier in the year when testing stopped once a home had five confirmed cases.

It also seems likely the re-introduction of shielding for the most vulnerable groups will need to happen at some point.

So how bad will it be?

It is of course impossible to predict - and depends on many different factors.

A leaked report obtained by BBC Newsnight suggested the government had been advised there could be 85,000 deaths under a "reasonable worst-case scenario".

Of course, the worst-case scenario should be avoided.

If we are to avoid returning to the scale of deaths seen in the spring - as Prof Hunter and others think is possible - that would mean limiting fatalities to under the 41,500 coronavirus deaths that have been seen during the pandemic.

But during any winter, deaths always increase by many thousands.

The worst one of recent memory was three years ago when an extra 15,000 more people died in England and Wales than had on average in the previous five winters.

It was a cold winter, the strain of flu was a little more virulent than normal and the vaccine available was not particularly effective.

This year in the fight against coronavirus there is no vaccine and very limited immunity.

Keeping the death toll anywhere near zero is, sadly, going to be impossible.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

- Published28 July 2020