Child obesity action 'risks losing its way'

- Published

Government efforts to fight child obesity risk getting lost in reorganisations and delays, a report warns.

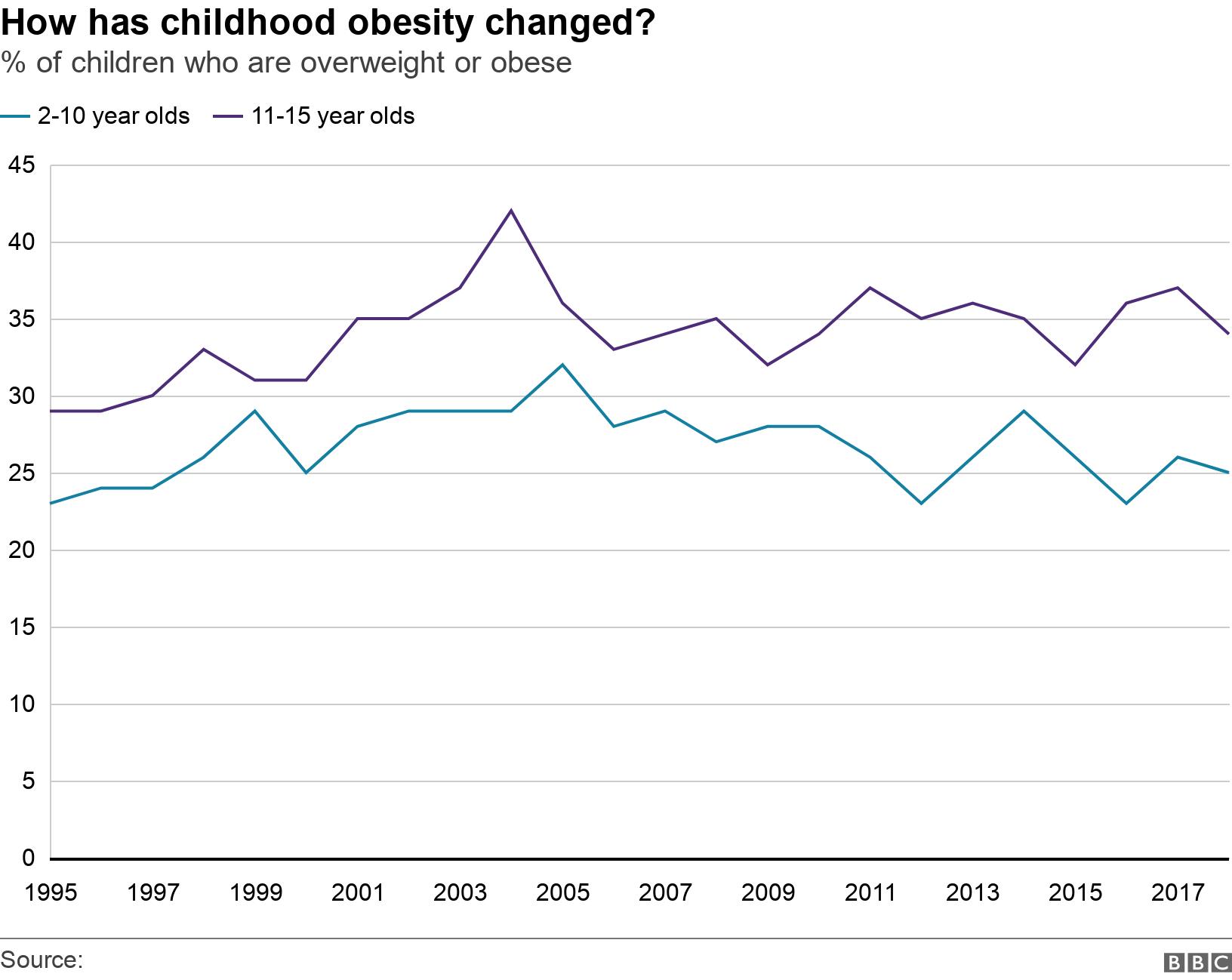

The National Audit office says 20 years of targets and policies have had limited success and new initiatives may fall short too.

It points to a lack of urgency and coordination, while the child obesity problem worsens in parts of the UK.

Britain has one of the highest child obesity rates in Western Europe.

A fifth of 10- to 11-year-olds are obese, according to latest figures for England.

Obese children are much more likely to become obese adults, causing significant health risks.

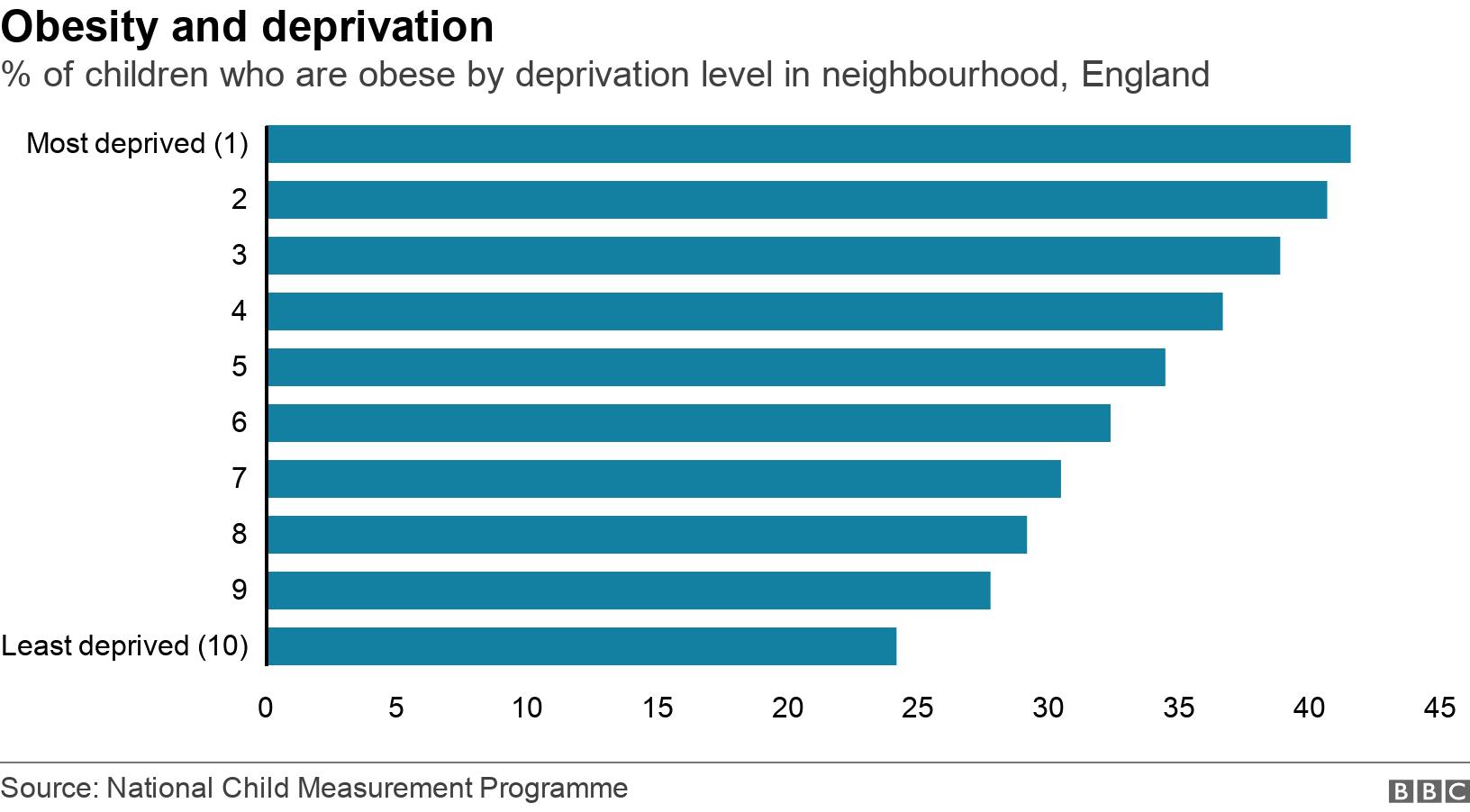

Children from deprived areas or ethnic minorities are far more likely to be obese - and the problem is escalating.

But few interventions in the child obesity programme specifically address this, the NAO report says.

Although the Department of Health and Social Care is responsible for setting and overseeing obesity policy in England, the cross-government nature of the child obesity programme means many projects are outside of its control.

In 2016, the government published the first chapter of its plan, external aimed at slashing the child obesity rate over the next decade, through measures such as a sugar tax on fizzy drinks.

A second chapter, external was published in 2018, promising to reduce the gap in obesity between children from the most and least deprived areas by 2030.

In July 2020 - amid growing evidence of a link between obesity and an increased risk from coronavirus - the prime minister set out the next steps, which include:

a ban unhealthy "buy one, get one free" deals

restrictions on junk-food advertising

calorie labelling on restaurant menus

But a ban on energy-drink sales to under-16s, mooted in 2018, has not gone ahead.

And other policies, including the sugar tax on fizzy drinks, have not been fully evaluated to see what impact they have actually had, the NAO says.

Without assessing the success or failure of past strategies, the government will struggle to prioritise actions or apply lessons to its new approach with confidence of success, the report warns.

Although there has been some progress in reducing sugar levels in popular foods, government will not meet its ambition to have industry reduce sugar by 20% in certain products by 2020, the report says.

There is also limited awareness and co-ordination across departments of wider factors and activities that may affect childhood obesity rates, such as sponsorship of sporting events by the food industry.

NAO head Gareth Davies said while the new strategy announced in July signalled "a greater intention" to tackle obesity, the government must now act with urgency.

'Bold action'

A Department of Health and Social Care official said: "We are determined to tackle obesity across all ages and we have already taken significant action - cutting sugar from half of drinks on sale, funding exercise programmes in schools and working with councils to tackle child obesity locally.

"We are also taking bold action through our new and ambitious obesity strategy... to help families make healthy choices."

But Dr Layla McCay, from the NHS Confederation, said it appeared the government had not learned from the failures of past efforts.

"This is such an important moment for effective action but it risks becoming lost amidst reorganisation and delays," she said.

"At a time when obesity is in the spotlight for putting people with Covid-19 at greater risk of needing hospital admission or intensive care, it has never been clearer that an effective approach is needed."

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health said money must follow commitments.

"As ever, the communities that need these services most are those that have faced the most severe funding cuts," it added.

- Published10 October 2019

- Published28 July 2020

- Published25 June 2019