Mother and baby units: 'It's our job to keep them safe'

- Published

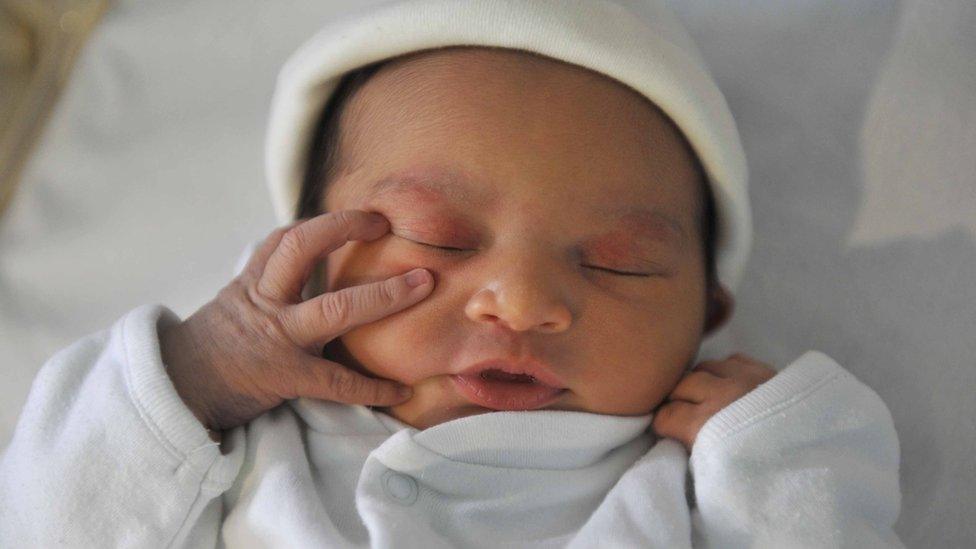

Kathryn Baughan said being pregnant during the pandemic caused her a lot of anxiety

"Women may be suicidal or want to die. They may have thoughts about harming their baby. It's our job to keep them safe until they can keep themselves safe," says Debbie Sells.

She manages a mother-and-baby unit in Nottingham which supports a small group of new mothers and pregnant women with serious psychological problems.

It's one of 19 units across England which each year treat about 800 women with perinatal mental health problems like psychosis and severe depression.

Clinicians say it is important to keep mothers and babies together to protect their relationship and the infant's development.

Units stayed open during lockdown, enforcing strict Covid-control measures to protect an already vulnerable community, but demand fell.

The NHS says it is vital women seek support if it's needed.

BBC News has been granted rare access to the unit.

'Hard working out what was real'

Kathryn Baughan needed treatment at the Nottingham unit after the birth of her son.

"I have never experienced mental health problems before, but I started experiencing postpartum psychosis symptoms shortly after I had my baby Ollie," she says.

"I had hallucinations and delusions, urges to do things I would never normally want to do.

"I relived my birth, which was really traumatic. I also thought Ollie and I didn't survive labour. It was really hard working out what was real."

Kathryn, 31, and Ollie were admitted to the Margaret Oates Mother and Baby Unit, run by Nottinghamshire Healthcare, when Ollie was just five days old.

"Being pregnant during the pandemic caused me a lot of anxiety because of all the changing rules," she says.

"I'm also a teacher and was having to try and do my job from home. It was a very confusing time."

Kathryn believes uncertainty surrounding maternity services because of coronavirus restrictions also played a role in her becoming seriously ill.

"I was in labour on my own for 13 hours because my husband Chris was not allowed on the ward."

Chris says: "It was extremely difficult. My wife was going through this horrible ordeal and I couldn't even hold her hand. Luckily I was able to be there for the birth, but after 90 minutes I had to leave again."

Aside from a few visits, Chris missed the first weeks of his son's life.

"At the start, there were lots of concerns.

"I didn't understand the illness. You're on a steep learning curve, but soon you start to see signs of improvement.

"It was really good when Kathryn and Ollie could come home. I know it's not over, but the worst bit is and now we're just focusing on getting back to normality."

Isolation issues

Caring for new mums during the pandemic has brought new challenges for the MBU.

Covid rules mean women have to isolate in a bedroom with just a single bed and a cot for 24 hours after they are admitted while staff wait for results of a coronavirus test.

Staff nurse George Kibaja says: "While they wait for the all clear, it can be really difficult for mums being in these four walls with their baby. It makes them not want to come to hospital."

During the initial isolation period, the only human contact patients have is with staff dressed in full personal protective equipment (PPE).

One woman, who didn't want to be identified, said: "I was already paranoid, so it was really scary the first time I saw people in masks and aprons. It's kind of like being in a sci-fi film.

"It makes you feel like you have a sickness, like if they come near me they will catch my mental health issues."

Some patients are reluctant to have a Covid test

Consultant perinatal psychiatrist Dr Zena Schofield says she and her team have to work much harder to build trust, especially while wearing PPE.

"This gear definitely interferes with our ability to build therapeutic relationships with our patients, and yet it's necessary because we don't want to spread the virus around patients and staff."

And patients do not always want to have a Covid test.

Dr Schofield describes how one acutely unwell young mum, detained with her new baby under the Mental Health Act, had declined a Covid test.

She had to be restrained and medicated for everyone's safety.

"Our patients are often very frightened and sometimes have beliefs that people aren't who they claim to be," she says,

Perinatal mental health problems occur during pregnancy, or in the first year following the birth of a child.

Figures suggest this can affect up to 20% of expectant and new mothers, and covers a wide range of conditions including depression, anxiety disorders and postpartum psychosis.

The most extreme cases can receive intensive support at an MBU, and the majority of patients are there on a voluntary basis.

While England has 19 units and Scotland two, there are currently none in Wales or Northern Ireland.

Care includes a range of therapies and advice on things like breastfeeding. Mums can also take part in group activities like cooking and painting.

After the drop in demand during lockdown, NHS England says admissions are now close to pre-Covid-19 levels.

However, some women are turning down care because of strict measures put in place to protect patients and staff from the virus.

While perinatal support in the community is available, manager Debbie Sells is concerned these women may not receive enough face-to-face contact.

"Things could escalate and get to a point where they need urgent help. The majority of these illnesses are recoverable. Early intervention is really important."

A particular deal-breaker for potential patients is the dramatically reduced visiting hours.

'Vital' to seek support

Debbie's ward in Nottingham has had to switch from a family-friendly place to only allowing one visitor per patient twice a week.

Winter will bring about further challenges.

"Currently visitors are not allowed on the unit, just in the garden," Debbie says. "This worked during the summer, but we can't expect families to sit outside in the middle of winter.

"We are now looking at how we can safely allow visiting on the ward, but are we going to restrict that to the bedrooms? Who will deep clean that? There's so much to think about."

And some clinicians fear there may soon be an increased demand for their services due to extra pressures pregnant women are facing during the pandemic.

"We are hearing stories of women delivering on their own and not having the support of their partner, says Debbie.

"A traumatic birth can lead on to other things. Now not only are women becoming seriously unwell with a baby, but it's happening within a pandemic"

NHS England says while it is understandable some women and their families may have felt uneasy about seeking help in the early stages of the outbreak, it is vital they ask for support if it is needed.

Support and information on mental health is available on the BBC Action Line page.

- Published29 September 2020

- Published26 September 2020

- Published26 June 2018