Coronavirus doctor's diary: 'We're no longer heroes - this is the new normal'

- Published

Paul Whitaker (back) with junior doctors and a nurse

Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary looks ahead to the difficulties to come this winter, and considers how much has changed since March.

The hospital remains in its own Narnia, locked down from visitors, with monastic corridors and deserted shops and coffee bars. The wards by contrast are busy and our A&E department is back to pre-pandemic activity with over 400 patients per day. The number of patients with Covid-19 has stabilised at around 80, 10 on ICU, not far off our peak in April, but unlike the first wave we are doing our best to keep all our services running as much as we can.

This time we know what we are doing; we have learnt hard lessons. Our treatments are better and we are managing patients with Teutonic efficiency and insightful compassion. The chaos of PPE shortages is a distant memory with scrubs and visors laid out in the ward donning rooms like a bespoke tailor's shop. (Having said that, the number of patients on oxygen did briefly cause oxygen shortage alarms earlier in the week.)

But there is another change. This time we are no longer heroes. This is the new normal.

Consultant in respiratory medicine Paul Whitaker notes that in spring "there was a sense of camaraderie and everyone was rising to the challenge". Now, he says, we're seeing "a kind of battle fatigue".

"So I think it's going to be a hard period, because I imagine this will go on for the whole six months, over winter and into spring. So it's going to test people's resolve and endurance to keep going."

The other major challenge he foresees is the task of keeping patients safe outside the red zone, where the Covid-19 cases are isolated. We are now effectively running two hospitals - the red zone and the green zone - and we know from the spring that controlling the spread of infection from one to the other is hard, if not impossible. This invisible coronavirus bundle of RNA has a knack of evading all our carefully prepared border controls. It is just not possible to run the Covid-19 wards as hermetically sealed units.

And this time the green zone is much busier. Doctors are juggling the workload of Covid and non-Covid cases, and while we assigned all staff to help with the pandemic first time round, our determination to keep other services going now will make rotas harder to fill.

In spring, Paul Whitaker notes, "we didn't have any non-Covid activity".

"For some reason those patients were keeping away from the hospital," he says. "Whereas now we've got high numbers of Covid, but we've also got high numbers of standard respiratory problems who aren't Covid-positive that we're seeing normally at this time of year. There are lots of other viruses going on and everything else."

Will there be a double whammy of flu and Covid-19? It's possible, though measures taken to control the transmission of one, should control the other, and signs from the southern hemisphere, where winter has already come and gone, and are positive. Flu cases there have dropped dramatically.

But while deaths from Covid-19 have so far remained low in Bradford this time round, Paul Whitaker doesn't expect this to last.

"I suspect, probably, the deaths will come - that's my feeling," he says. "We have had some slightly younger patients, who have some comorbidities or diabetes or hypertension or obesity. We haven't quite had the same numbers of very elderly, frail or nursing home residents that we have before. But I suspect it's only a matter of time. And I don't think it's that Covid is necessarily behaving less aggressively."

Prof John Wright, a doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio.

Listen to the next episode of The NHS Front Line on BBC Sounds or the BBC World Service

Or read the previous online diary entry: A heartbreaking insight into the impact of lockdown

I spoke to two patients on the Covid wards receiving treatment guided by the routine that is now so familiar. Both were brought in with low blood oxygen levels, were put on oxygen with CPAP, and quickly improved.

Ian, a semi-retired accountant, says he doesn't know how he caught the virus.

"After the first lockdown, when they took the brakes off, we carried on being careful," he says. "We haven't even been going round to see people, and we've been wearing masks whenever we went shopping. We tried so much to not catch it."

Mark, by contrast, thinks he may have caught the virus from a colleague whose wife, Helen, works as a receptionist at a college, and is therefore exposed to young people, who may in some cases be failing to take adequate precautions

Mark Ingram - a colleague's wife was alerted by test and trace

Helen got a message from track and trace to say she had been in contact with someone who had tested positive. She tested positive herself a week ago last Wednesday, and Mark, already feeling very tired, decided to get tested on Thursday. His test came back positive on the Saturday - his 48th birthday - and two days later paramedics said he'd have to come in.

Mark's story shows test and trace working as it should. But sadly the government's national test and trace system, such a crucial element of keeping Covid-19 rates under control, is currently managing to contact less than half of all potential SARS-CoV-2 cases in Bradford (people who have come into contact with someone who has tested positive). Nationally the figure is 65%, which is not much better - and it's estimated that less than 20% of those actually contacted go on to isolate.

The week at least started with something positive - some unexpected praise for Bradford from the Chief Medical Officer, Chris Whitty, external, for the great work in tackling the pandemic from the city's communities, local government and NHS. There has been no shortage of self-appointed experts on Covid-19 during the last six months, each with their own opinion on how the pandemic should be managed, but the CMO, as an epidemiologist and infectious disease specialist, is without doubt the right person at the right time in the right job, and his feedback has lifted spirits greatly.

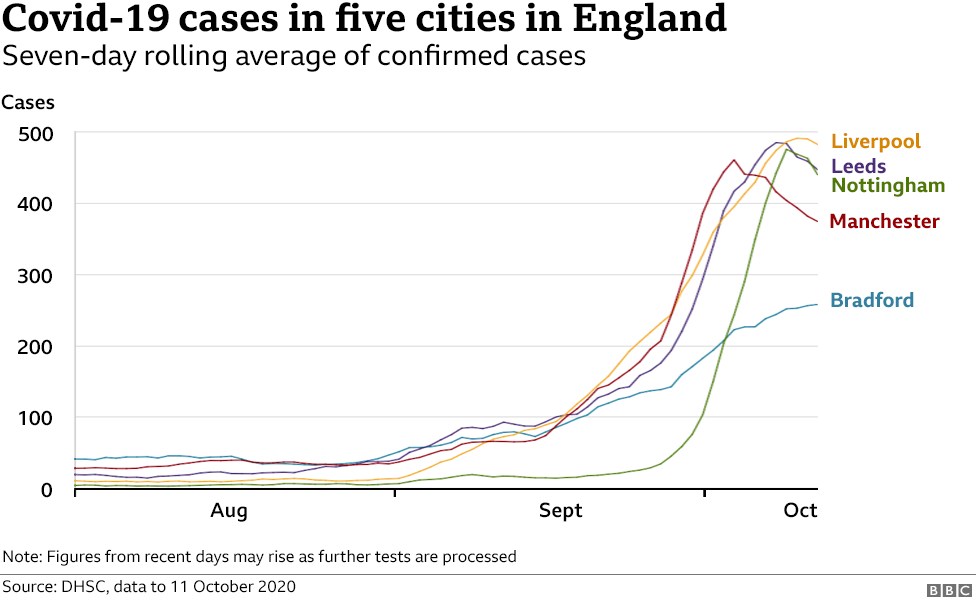

Bradford does indeed seem to have coped well in recent weeks, balancing the health consequences of the virus with the economic consequences of restrictions. Numbers of cases have risen much less steeply than in some other northern cities, Manchester, Liverpool, and Leeds, for example (see the graph above). We keep looking for signs of hope in the plateauing of the curves, but if there is one certainty that Covid-19 has taught us, it is never to be certain.

Follow @docjohnwright, external and radio producer @SueM1tchell, external on Twitter

LOCKDOWN LOOK-UP: The rules in your area

SOCIAL DISTANCING: Can I give my friends a hug?

FACE MASKS: When do I need to wear one?

TESTING: How do I get a virus test?

YOUR WORK, YOUR MONEY: Is my bar business better off in Tier 3?

WHAT PLANET ARE WE ON: Sir David Attenborough talks about the impact of the pandemic on tackling climate change