Ethnic minority Covid risk 'not explained by racism'

- Published

A scientist advising the government on ethnicity and Covid says "structural racism is not a reasonable explanation" for black and south Asian people's greater risk of illness and death.

An earlier report by Public Health England said racism may contribute to the unequal death toll.

Dr Raghib Ali suggested it was time to stop using ethnicity when deciding who needed help.

He said focusing on factors like jobs and housing would help more people.

The newly appointed expert adviser said this approach would help prevent everyone at risk - including poorer white groups living in crowded housing - from missing out on help.

But Dr Chris Udenze, a GP who has also worked in public health, said it was important not to dismiss ethnicity.

He told the BBC: "I think the whole thing is very complicated. Ethnicity is not the only factor but it is definitely one of many factors.

"All the other factors such socioeconomic factors, diabetes etc are important but even if you were able to take these away, there is still a disparity. Ethnicity is still a relevant factor and not paying attention to this will not help communities vulnerable to Covid."

He added: "Similarly, structural racism may not be a reasonable explanation by itself but it is one of many factors that contributes to disparity and this has been backed up by many reports.

Dr Ali made his comments during a briefing on the first quarterly report on Covid disparities, led by the government's Race Disparity Unit and the Minister for Equalities, Kemi Badenoch.

The document is a stocktake of the actions taken and evidence gathered since previous analyses by Public Health England, which set out the greater risks faced by black, Asian and other ethnic minority groups.

One previous report by Public Health England, published in June, said: "Historic racism and poorer experiences of healthcare or at work may mean that individuals in BAME groups are less likely to seek care when needed or as NHS staff are less likely to speak up when they have concerns about personal protective equipment or risk."

BAME coronavirus deaths: What's the risk for ethnic minorities?

What did the latest report say?

To find out more about why the increased risks exist for certain ethnic groups, the authors reviewed recent studies, including figures from the Office for National Statistics, and Public Health England.

While no single study was able to examine all the possible reasons, the report agrees with previous analyses that a range of factors are involved.

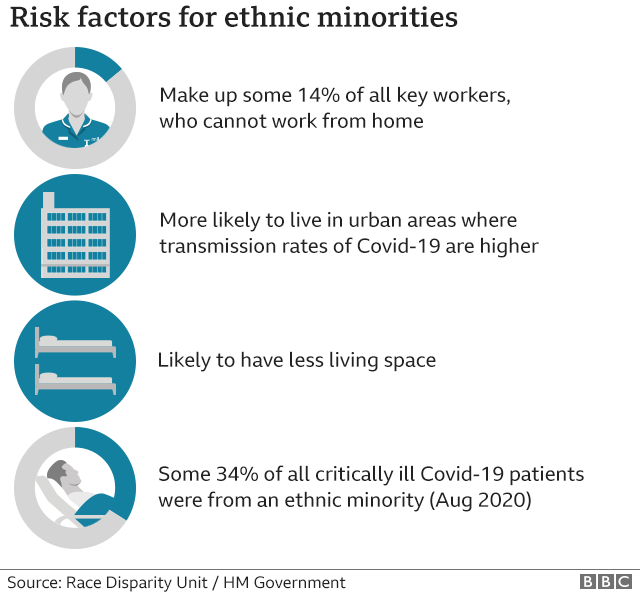

These include:

Where people live - with a higher risk in urban areas with greater population density

Occupational exposure - for example data shows Black people are more likely to work in healthcare than other groups

Household composition, with larger households at greater risk

Pre-existing health conditions - such as obesity, which can make it harder to recover from the virus

Dr Ali said that while studies often differed in their conclusions, the older people are, and where they lived, were two of the biggest factors behind the increased risks.

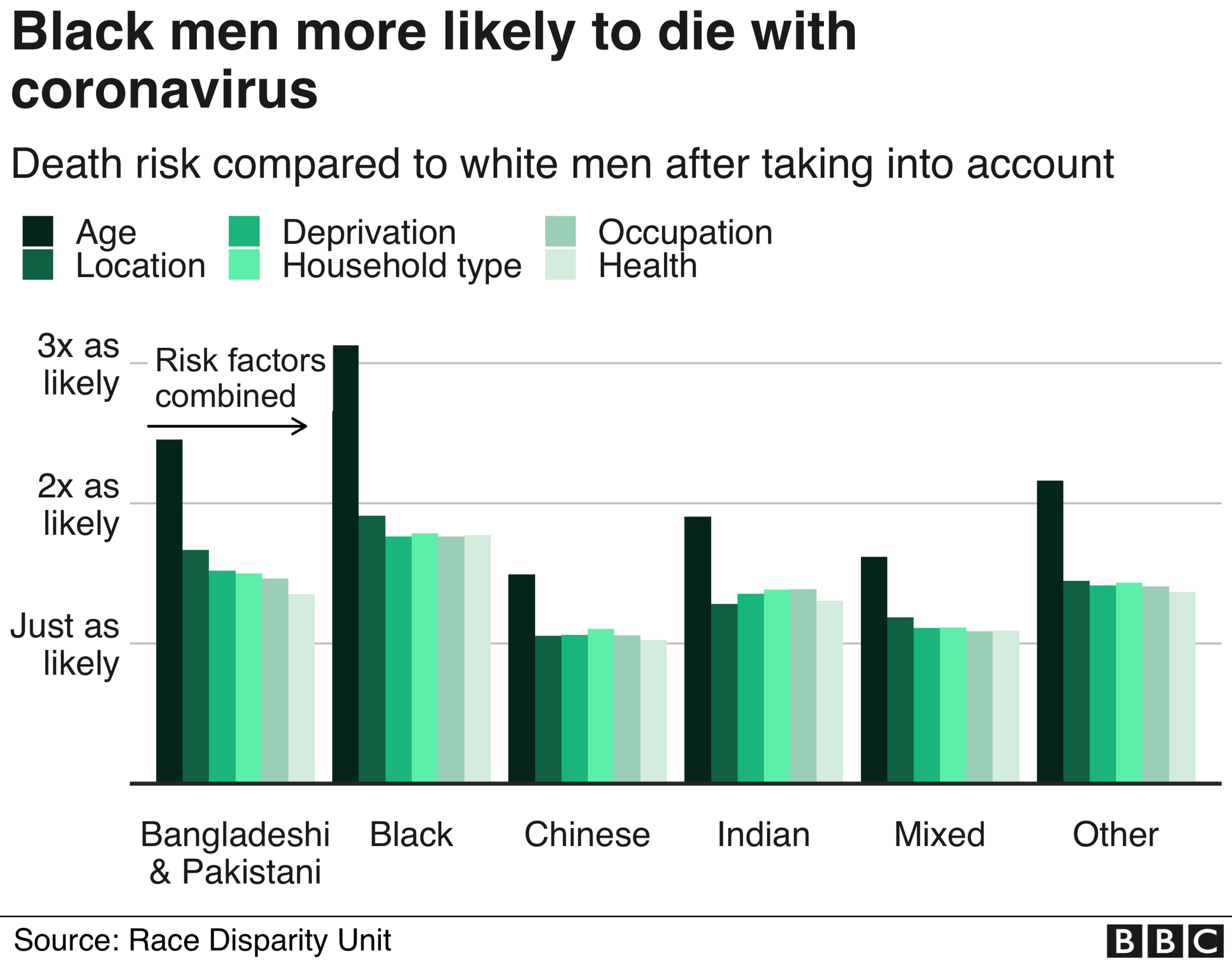

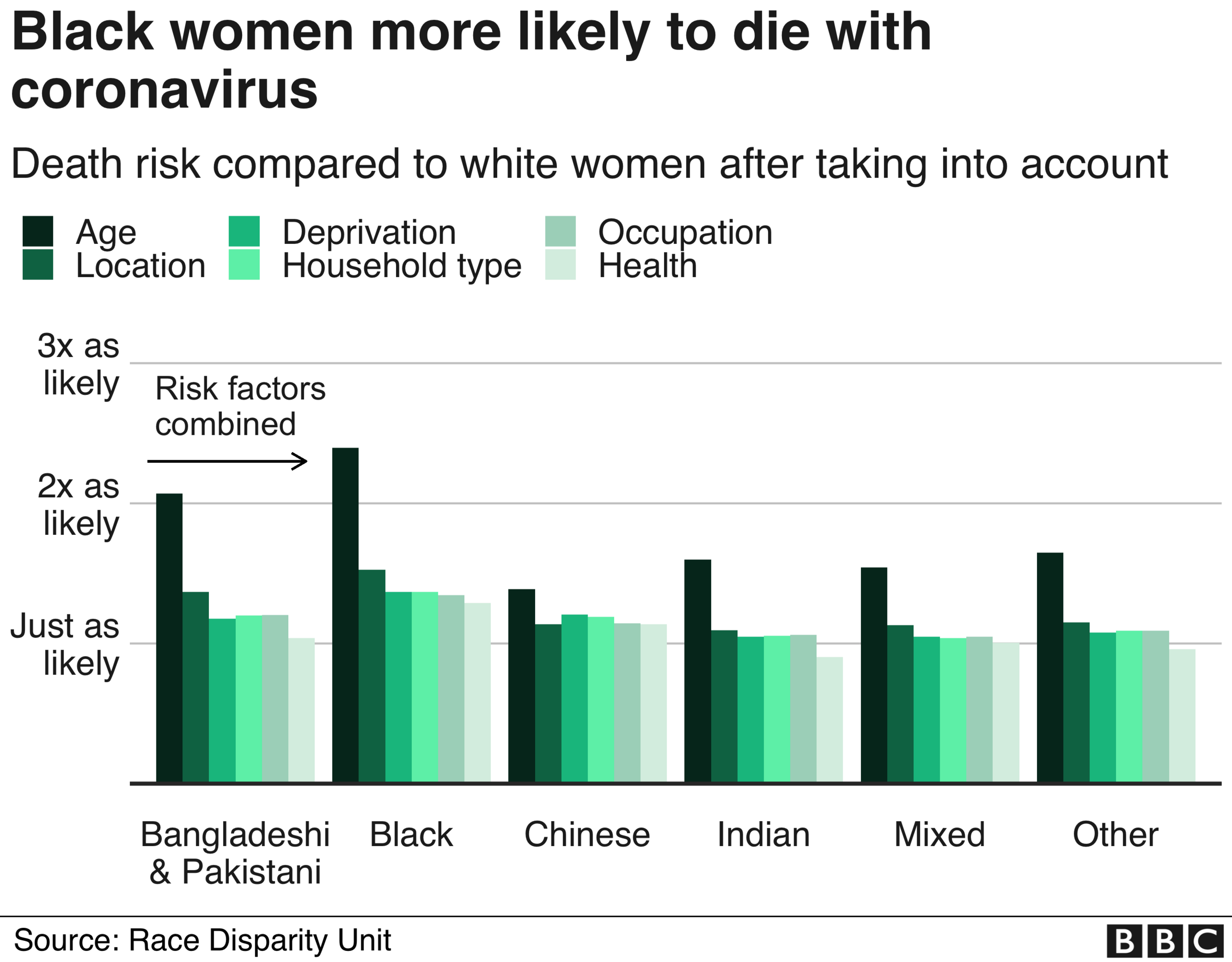

He added that much of the increased risk faced by ethnic minorities could be explained by factors such as the ones mentioned above.

But he agreed with the report authors that a "small part" of the excess risk remained unexplained for some groups.

Some data shows even when multiple risk factors are put together and taken into account, black and other ethnic minorities are still at an increased risk of death

Perhaps the most noteworthy conclusion of this report by the government's Race Disparity Unit is that "a part of the excess risk remains unexplained". Nine months into the Covid-19 pandemic it is still not totally clear why BAME communities are more vulnerable to the virus and more likely than others to become seriously ill or die.

The report runs through familiar themes, such as occupations with higher risk of exposure to the virus, underlying health conditions, concentration in densely-populated urban areas and multi-generational households. But it does not uncover any new explanations.

The expert adviser Dr Raghib Ali rules out "structural racism" though others will disagree, arguing that historic experiences of discrimination may deter people from seeking healthcare or adequate protection at work.

Ministers acknowledge that there is more work to be done but important steps have been taken to improve monitoring and gather further evidence. However, with a second wave of coronavirus now evident and winter approaching, there will be continuing apprehension among some in ethnic minority groups.

What changes are being made?

It will become mandatory for ethnicity to be recorded on death certificates as "this is the only way of establishing a complete picture of the impact of the virus on ethnic minorities". This will involve patients being asked about ethnicity during consultations with their doctors.

A community champions scheme will help increase tailored communication and advice for communities most at-risk and fund grassroots groups.

Recommendations in the report include:

Risk assessments at work for everyone, not just people from ethnic minority groups, to avoid stigma and help protect all people in need of support

A risk calculator tool is being developed by the University of Oxford to help doctors and individuals understand more about their risks from Covid.

Minister for Equalities, Kemi Badenoch, told the BBC: "Quite often people expect there will be announcement that will be specifically just for ethnic minorities but actually the risk profile for vulnerability goes across many different groups.

She added: "We have made sure all of the work we have done, all of the action taken to safeguard people's lives have been done across the population as a whole, with a particular focus on the vulnerable."

Dr Raghib Ali

What was said on ethnicity?

In the briefing, Dr Ali said: "The problem with focusing on ethnicity as a risk factor is that it misses the very large number of non-ethnic minority groups, so whites basically, who also live in deprived areas and overcrowded housing and with high risk occupations."

He added the whole population should have a "personalised risk assessment" rather than just targeting ethnic groups.

"It doesn't make sense to put all ethnic minorities in the same basket as it doesn't make sense to put all whites in the same basket," he said.

On structural racism, he said he was not convinced by the narrative that racism played a part in coronavirus deaths.

He pointed out that generally people from BAME backgrounds have better health outcomes than other groups.

Meanwhile the Institute for Public Policy Research, said: ""As the government's report rightly says, disparities in Covid-19 are driven by structural differences between ethnic groups in terms of deprivation, living conditions and low-wage public facing jobs. We agree. Let's call this what it is - structural racism.

"The academic literature is clear - race and ethnicity are determinants of health. It is outlandish it suggest otherwise."

What did the experts say?

The doctors' union, the British Medical Association, said there needed to be tangible action right now to protect Black, Asian and ethnic minority people.

"As we sit amid a second wave of infections, we know that about a third of those admitted to intensive care are not white - showing no change since the first peak," said Dr Chaand Nagpaul, BMA council chair.

"Meanwhile, black and Asian people have been found twice as likely to be infected compared to white people."

GP, Dr Hajira Dambha-Miller, said she welcomed the comprehensive report.

But she added: "Further detail is still needed in explaining why BAME groups are more susceptible to worse outcomes. I don't think the report goes far enough in exploring the wider social factors that may contribute to viral transmission and death."

- Published11 June 2020