'Covid killed my wife - so I'm taking part in a vaccine trial'

- Published

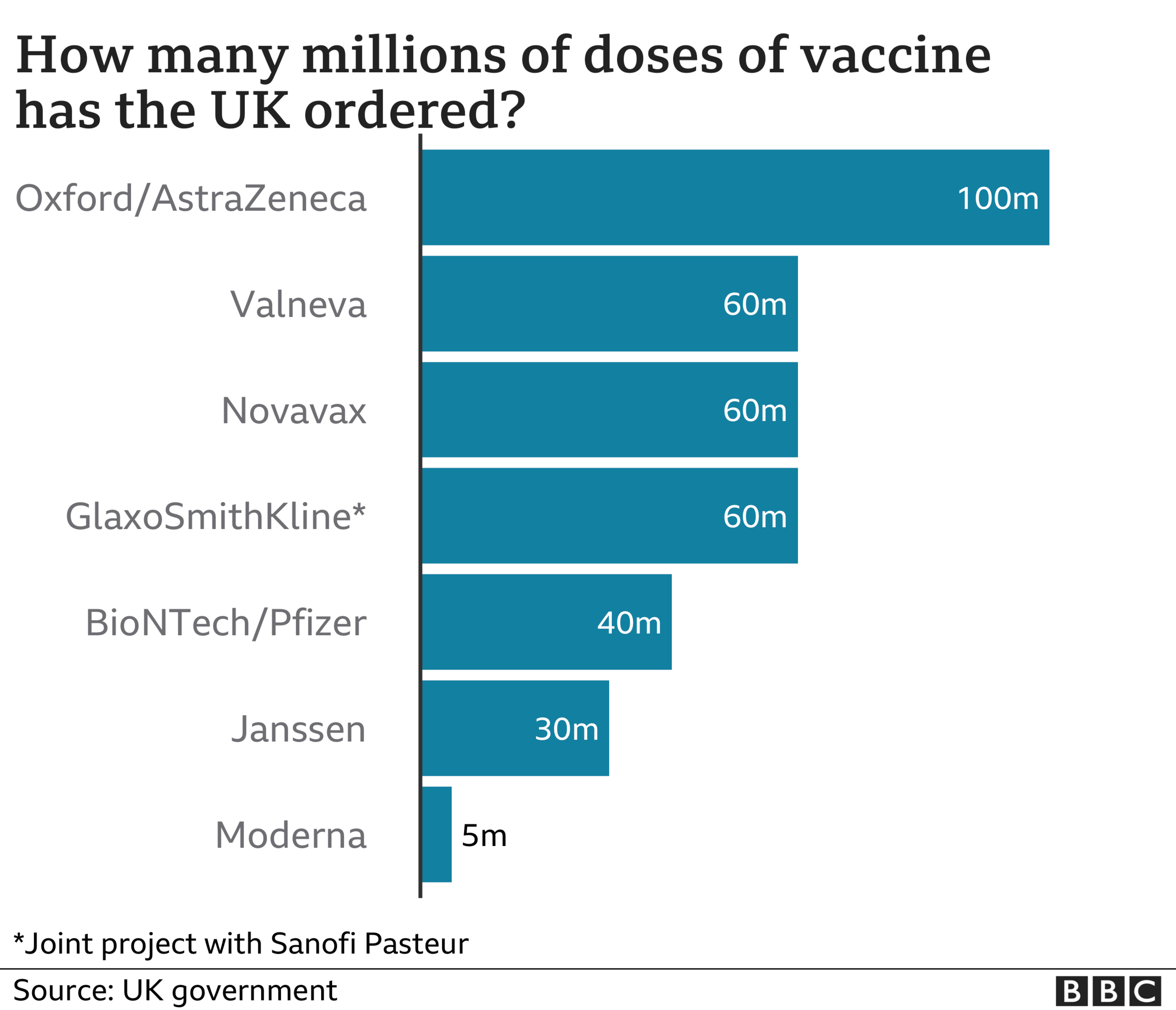

While one Covid vaccine has been approved for use in the UK and two are awaiting approval, many more are still being tested. The UK has pre-ordered 60 million doses of the Novavax vaccine, which is currently undergoing phase three trials. Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary talked to one man about the personal tragedy that prompted him to volunteer for the injection.

Pauline Demaline was fit and healthy and only 56 years old when she fell ill with Covid-19 in March. But within days of going into hospital she was dead.

She worked as a parish administrator at the Holy Trinity parish church in Skipton and it may be here that she caught the virus, in the early days of the pandemic.

She and her husband, Nigel, were very careful. They didn't go out much and Nigel would do the shopping early in the day, when the shops were quiet. But Pauline had to go into work and would sometimes meet other parishioners - couples about to get married, for example, and their parents.

At a certain point, she began feeling tired.

"It seemed like she would be exhausted when she finished work," says Nigel. "She came home and lay down on the settee. I don't think she had a temperature, but she felt rotten. She had a bit of trouble with breathing but thought it was her normal asthma.

"People were telling her to see a doctor but she wouldn't go. She thought she'd be all right, that it would pass."

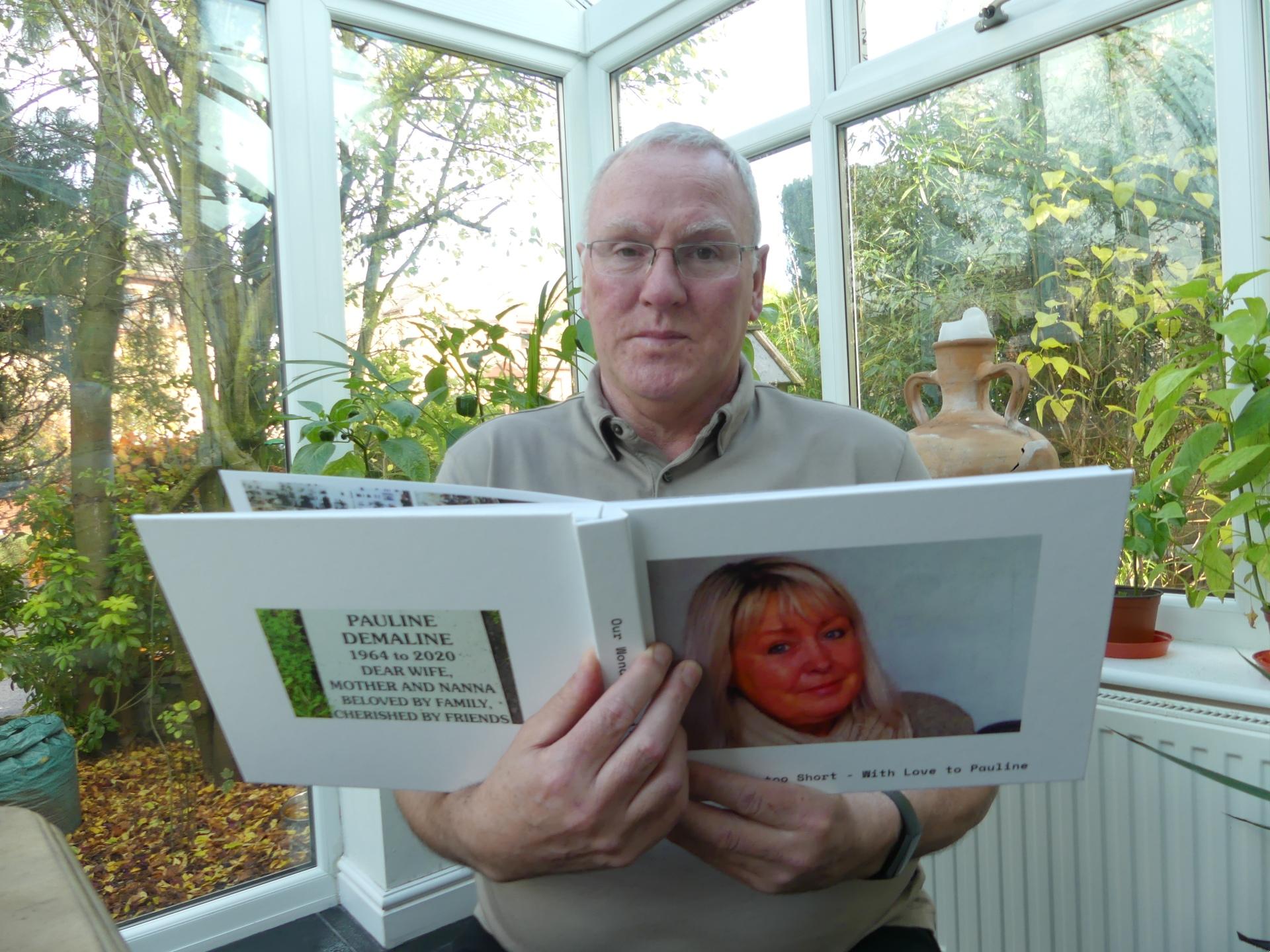

A recent photograph of Pauline

Eventually Nigel forced Pauline to get help.

"I said to her, 'You've got three choices: I can either get you to the doctor's, I can call an ambulance, which you'd hate, or I can take you down to accident and emergency.' Our neighbour across the road, Rachel, was home. So she had the dogs and I took Pauline to the hospital, not knowing that that was the last time she was going to leave the house."

At accident and emergency she was given a Covid test and put on an isolation ward. That test came back negative and doctors were preparing to move her but then an X-ray of her chest made them change their mind.

"It was about four hours later that the consultant came back to say sorry, it was a false negative," Nigel says. "He said they were experiencing about 75% false negatives at that point, because the tests that they were doing were so new."

Then Pauline's condition deteriorated very fast.

"The next time the consultant saw me and my son he said it's not a matter of if she'll die, it's a matter of when she'll die. We asked about the timescale and he said two days, maybe three days at most. And that was the first time that I suddenly thought, 'This is serious. This is real.'"

Pauline went into hospital on Wednesday 25 March. The conversation with the consultant happened on the Friday. On Sunday Nigel and his son spent all day with Pauline, who was by now having great difficulty breathing, and on Monday 30 March she died.

"Just after Pauline died - and this is something I've never shown anyone else - I took a picture of her, of how unwell she was," Nigel says. "And I look at it quite regularly because it reminds me of how she was, and it's so sad - that was how she was after her last breath. It's just something to hang on to, and of all the photos I have it's the one that upsets me the most, but gives me the most comfort. The memory is not out of reach. It's not out of grasp. It's there. It's really tangible. I can look at it."

The couple met when Nigel was 16 and Pauline was 15. He'd left school and joined the forces as a musician, and in July 1979 his military band was in the Isle of Man to celebrate the 1,000th anniversary of the island's parliament, while Pauline was on holiday there with a friend. They met on the sea front in Douglas, when Nigel recognised Pauline's friend from their home town.

The following year he joined other members of his regiment, the 16th/5th The Queen's Royal Lancers, stationed near the East German border, and in 1982 they married. "We were very young but it was such a natural thing to do," Nigel says.

Nigel and Pauline always loved to travel

They had seven more years of Army life before moving to Silsden in West Yorkshire. Nigel worked in the motor trade and initially Pauline went to work for North Yorkshire Police in Harrogate. When she was asked to commute further, to a different office, she got the job at the church.

"She told me later that she'd always known we'd marry, even when she was just 15 and we started our relationship. I thought we were going into our 80s together," Nigel says.

He had always assumed that he would die first. Pauline's only health problem was asthma which had been well-managed since childhood.

"It's so overwhelming - the feeling of futility sort of sweeps across you," Nigel says. "You think, 'I couldn't do anything!' I wanted to do something but I couldn't."

Nigel doesn't know if he was infected with Covid at the time of Pauline's death - he wasn't tested - but because he visited her at the Airedale General Hospital near Keighley, he had to isolate for two weeks afterwards, and now wonders whether he did then have some symptoms.

"That period is all a bit of a haze. I think I've blacked a lot of it out," he says. "But I cried so much. I'd be sat there, the television would be on, and I couldn't tell you what I watched. I'd also be waking up in the early hours of the morning and my chest felt tight. Was it grief? Or was it that I had Covid, but just had very mild symptoms? I don't know."

It was Nigel's grief that spurred him on to become one of the first volunteers for a vaccine trial at Bradford Royal Infirmary, when he saw an appeal for volunteers on Facebook.

"I clicked on it without giving it a second thought. I thought, 'I need to be doing that.' I just felt the urge and the need to do it," he says.

"I wanted to do something to help. I really didn't want anybody else to go through what I was going through."

And this is how I came to meet Nigel at one of the hospital's Monday vaccine clinics acouple of months later. I told him he was doing a wonderful thing.

"People have been saying I'm brave - I'm not," he replied. "I can't do anything else but be brave. You've got to get on with life. I want to feel like I'm doing something."

The Novavax trial that Nigel is taking part in is the first of two that we plan to run in Bradford, and will be followed in January, by a trial of the Sanofi Pasteur vaccine developed with GlaxoSmithKline.

Why are we doing this when the results from the Pfizer, Moderna and Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine trials have been so good?

Well, the more options we have to vaccinate the world's seven billion inhabitants, the better. This will help ensure we have effective vaccines for different population groups, provide safe alternatives should one of the vaccines turn out to have unexpected side effects, drive down cost (which is crucial for low- and middle-income countries) and offer simpler options for manufacture and distribution.

There are some 200 candidate vaccines in development and more than 40 now going through clinical trials.

The goal, in all cases, is to trigger our bodies to produce antibodies that will coat the virus and stop it from having its deadly effect, but never before has such an array of new technologies been used.

Front-line diary

Prof John Wright, a doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio.

Listen to The NHS Front Line on BBC Sounds and the BBC World Service

Or read the previous online diary entry: The Yorkshire cemetery struggling to keep up with burials

Click here to listen to Nigel Demaline's story on Radio 4's The Untold

The traditional approach pursued by the Oxford/AZ team is to develop a weakened virus to trigger this response in the same way as a natural infection would. The novel Pfizer and Moderna vaccines stimulate antibodies by using Covid-19 messenger RNA (a single-stranded molecule of RNA) to prompt our own cells to produce a harmless piece of the spike protein found on the surface of the coronavirus, which also leads to the production of antibodies.

The Novavax vaccine has been developed in the US and is being trialled in the UK on 10,000 volunteers. It uses proteins extracted from the coronavirus spike to trigger the body's immune response, and like the Oxford vaccine it has the important advantage of being stable at normal fridge temperatures, so does not require expensive transport or storage solutions. This will be vital in less developed countries.

The real heroes of this remarkable triumph of science, though, are not the scientists or the clinical researchers, but the thousands of trial volunteers who have stepped forward, like Nigel, to be human guinea pigs. Every Monday I have the privilege of seeing their courage and altruism.

My colleague Dinesh Saralaya taking a blood sample from a Novavax volunteer

I take consent from each participant, conduct a physical examination and take blood tests for antibodies. The volunteer then gets randomised to either the active vaccine or a placebo of saline solution. It is a double-blind trial, so I don't know what they get and the participant doesn't know. After three weeks they return for a booster and then get followed up after three, six and 12 months.

The vaccine is successful if it causes no serious side effects and if only a small proportion of those who receive it later come down with Covid-19. But whenever the participants return to the clinic their blood is also tested for antibodies. If they have high levels of antibodies for a long period, that is a good sign.

When Nigel came back for his booster injection, he was keen to know whether the blood taken on his first visit showed signs of antibodies, which would have revealed whether he had been infected with the virus around the same time as Pauline. I explained that I couldn't tell him, because I didn't know - this being a double-blind trial - and also because if he were to learn whether he had antibodies, this could affect his behaviour and therefore influence the outcome of the trial.

Pauline's funeral had to be delayed for two weeks, while Nigel was isolating.

There was then a very small service for just her five closest family members, though it was all videoed and there was a live link so that other friends and relatives could watch online.

In his eulogy, Nigel began by explaining why the service had begun with Every Day Hurts by Sad Café, a memory of the time when he was living in Germany and she was in the UK. "This was the first single I bought for Pauline and represented the fact that we were 300 miles apart and I missed her profoundly," he said.

He ended by noting that many people would miss her now, and that he would most of all. "Forty years together has had a profound effect on my life, and I will be very sad for many years to come," he said. "Pauline, I always have and will always love you dearly. Rest in Peace and sleep soundly my love."

Pauline and Yorkshire terrier Harry, in 2006

By a tragic coincidence, Nigel had suffered another loss almost simultaneously, when one of the family's two dogs, Harry, a Yorkshire terrier, died in his sleep.

"They were both cremated on the same day, 15 April, and I got calls from the funeral director and the vet's on the same day to pick up the ashes," Nigel says. "I came home with my wife in one carrier bag and our dog in the other."

At the back of the church there's a headstone marking where Pauline's ashes are laid, with the inscription: "Pauline Demaline, 1964 to 2020. Dear wife, mother and nanna, beloved by family, cherished by friends."

"And she was cherished," says Nigel. "I'd like to think she's there. I like to think of spirits there. And I just try to talk to her - to tell her the news, what's been happening, how people are, and thinking that she's listening."

He thinks Pauline would approve of the vaccine trial.

"I think she would be proud of what we're doing, and although it's too late for her she would be hoping it works for everybody."

Follow @docjohnwright, external and radio producer @SueM1tchell, external on Twitter

SOCIAL DISTANCING: What are the rules now?

FACE MASKS: When do I need to wear one?

TESTING: What tests are available?

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?