Covid: How close is the light at the end of the tunnel?

- Published

The roll out of the biggest vaccination programme in the history of the UK is under way. This week, some GP practices in England will join the major hospitals in starting to offer the jab.

The plan is to immunise all over-50s plus younger adults with underlying health conditions. The rest of the population could then follow suit. But how long will all this take?

Do we have enough vaccine?

Vaccinating 55 million people - children are not being considered for the jab at this stage - is a mammoth task. It will take many months, perhaps the best part of a year.

There is currently one vaccine approved for use - made by Pfizer and BioNTech.

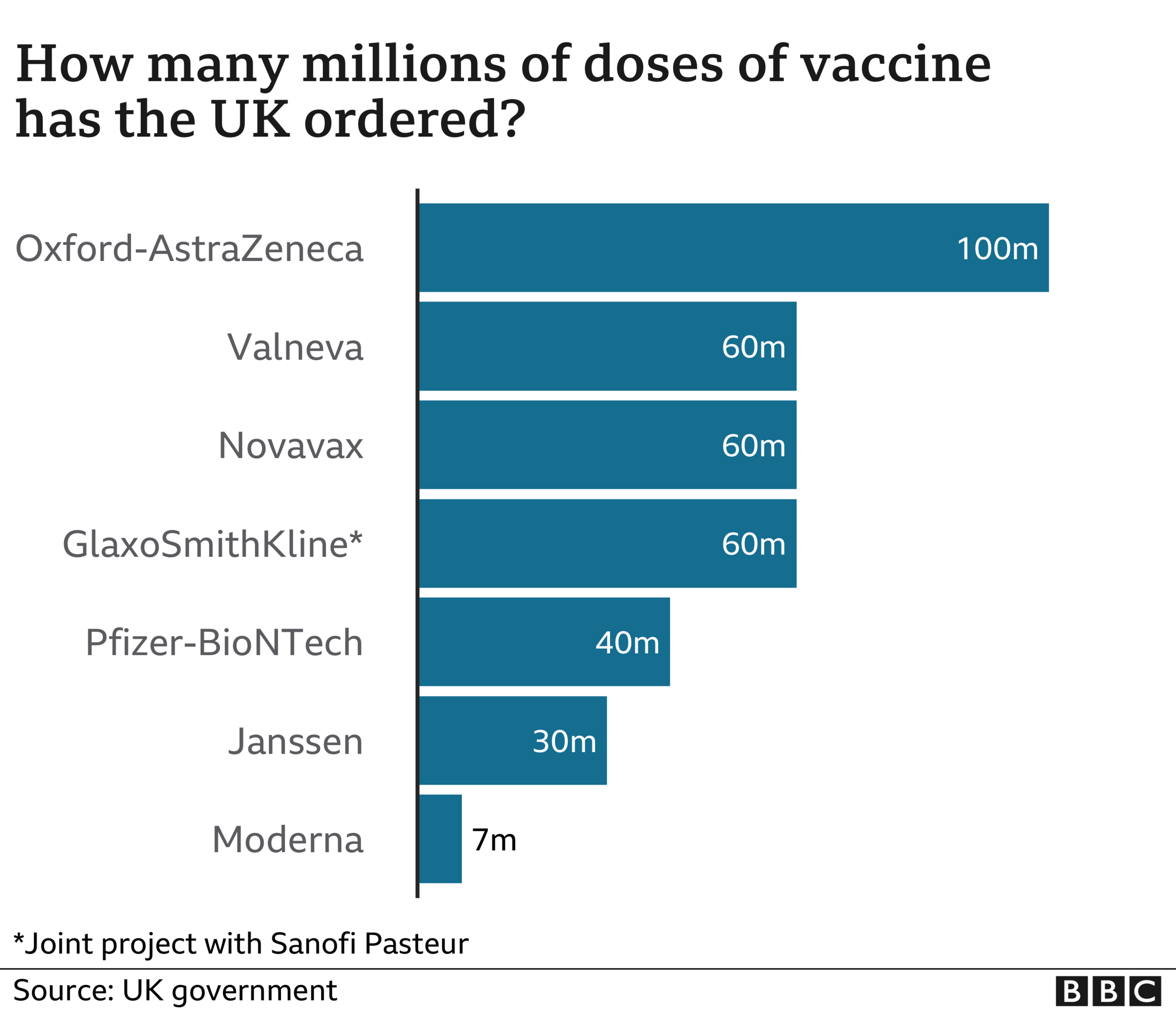

The UK has managed to order 40 million doses of the vaccine, enough to cover 20 million people given that two doses are needed.

So - in the short term at least - the UK will require another vaccine to be approved for use.

Fortunately, the regulators are assessing the merits of two more, including one made by US firm Moderna. But the problem with that one is the UK has been able to order only seven million doses - and the earliest they can be supplied is spring.

That is why so much hope is pinned on a vaccine produced by Oxford University and AstraZeneca.

Why Oxford vaccine is essential

There are already between five million and 10 million doses waiting go to with a total of 100 million on order - again two doses are needed so that's enough for 50 million people, which combined with the Pfizer jab means there should be enough for the whole population next year.

Will it be approved? It will be a surprise if it isn't. The team behind it are confident, stressing they had met all the criteria for approval when the full data behind the clinical trials was published in the Lancet this week.

Much was made of the fact that it does not appear to be as effective at stopping infection as the Pfizer vaccine - 70% v 95% effective - but what both do at close to 100% levels is stop serious illness. If people are not dying from Covid or being left with long-term problems, the most dire consequences of the pandemic are over.

What is more, roll out will be easier with the Oxford vaccine. That's because it does not need to be kept in ultra-cold storage like the Pfizer one, which has resulted in strict rules around its movement.

For example, the NHS is still not able to take it into care homes, despite residents and staff being the top priority for vaccination, while GPs have only three and a half days to use up doses when they get delivered. It is, says one GP, "a logistical nightmare" to work with.

Will supply be quick enough?

Vaccine manufacture is notorious for not always going smoothly.

Indeed, Pfizer has already had to reduce the amount it is expected to deliver to the UK - it is being shipped in from Belgium.

Originally 10 million doses were forecast by the end of 2020, but now the government has been told to expect only five million - and only 800,000 of that is currently in the country, making Health Secretary Matt Hancock's aim of vaccinating "millions by Christmas" looking like a stretch.

The Oxford vaccine is made in the UK, so from that point of view supply should be more reliable. However, production will still depend on the right ingredients being available, and with a global race to produce vaccines now well under way, it would be amazing if that did not mean a few hiccups along the way.

Another potential hurdle is Brexit. A no-deal Brexit could cause problems importing all sorts of goods, especially through the Calais-to-Dover shipping route. The government says it has identified secure routes to get essential goods into the country. But concerns obviously remain.

All this combined is why Dr Richard Vautrey, who is the British Medical Association's GP leader, says supply is probably the biggest "risk factor" to roll out.

He says if there is enough vaccine, he is "confident" GPs and their practice nurses could vaccinate millions of people a week.

What about vaccine hesitancy?

Vaccination on a mass scale is dependent on people coming forward. Many fear achieving good uptake is not a given because people may refuse to be vaccinated - it will not be compulsory.

Ipsos Mori and King's College London looked at this over the summer, external. Their survey of more than 2,000 adults was reported to have found just half of people were planning to get vaccinated.

The truth though is somewhat more nuanced. If you add in those who said they were fairly likely, the numbers jumped to nearly three-quarters.

What is more, the older age groups were the least likely to say they would shun the vaccine.

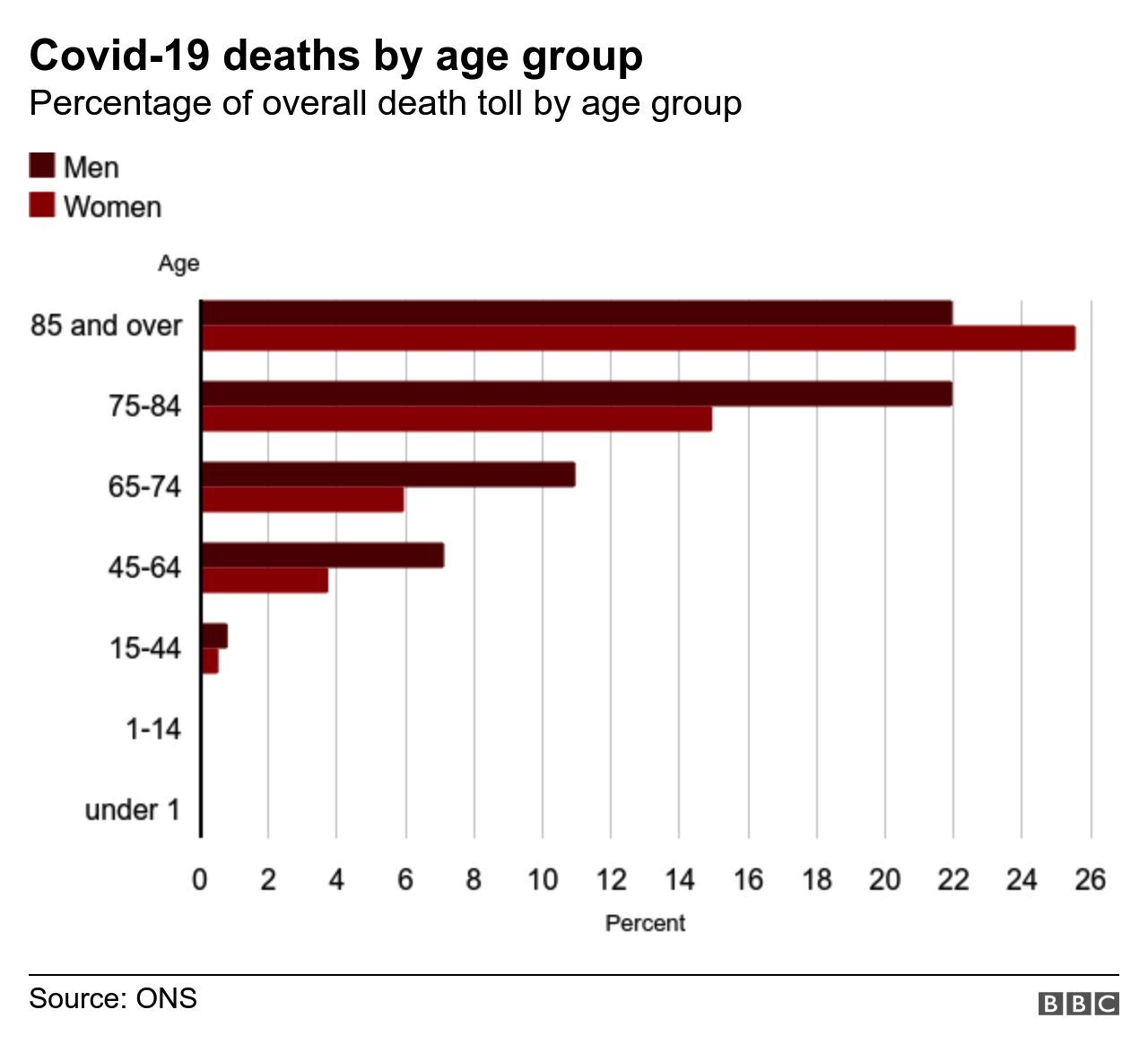

Understandably so, as they are the most at risk. More than nine in 10 deaths are among the over-65s - and this is really the crucial issue when it comes to the vaccine programme, and how quickly it will return life to normal.

We don't need to jab everyone to end worst of pandemic

There are 12 million over-65s. Once significant numbers are vaccinated, the risk of the NHS being overwhelmed disappears and the high number of excess deaths being seen across the population dwindles.

How long will that take? Well, GPs managed to vaccinate the over-65 population against flu in a little over two months this autumn - 77% came forward for the jab.

The flu jab is given in only one dose, but doctors believe it should be perfectly possible to finish immunisation for every person over 65 who is willing to have the vaccine by the end of March, availability permitting.

That would then trigger - or at least give the option of triggering - a major relaxation of restrictions.

It is what the UK government's chief medical officer Prof Chris Whitty referred to as "de-risking" this week, when he appeared before MPs at the Health Select Committee.

His point was that we could quickly reach a situation at which the level of death and illness caused by Covid was at a level society could "tolerate" - just as we tolerate 7,000 to 20,000 people dying from flu every year.

That would allow a gradual move away from the most severe restrictions, he says, perhaps just requiring a bit of continued social distancing and the wearing of face-coverings in some settings.

Spring may not be the end of the pandemic, but it certainly should be the beginning of the end.

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020