Covid: Can we really jab our way out of lockdown?

- Published

- comments

With the country in lockdown and a new faster-spreading variant of coronavirus rampant, it's clear the UK is in a race to vaccinate.

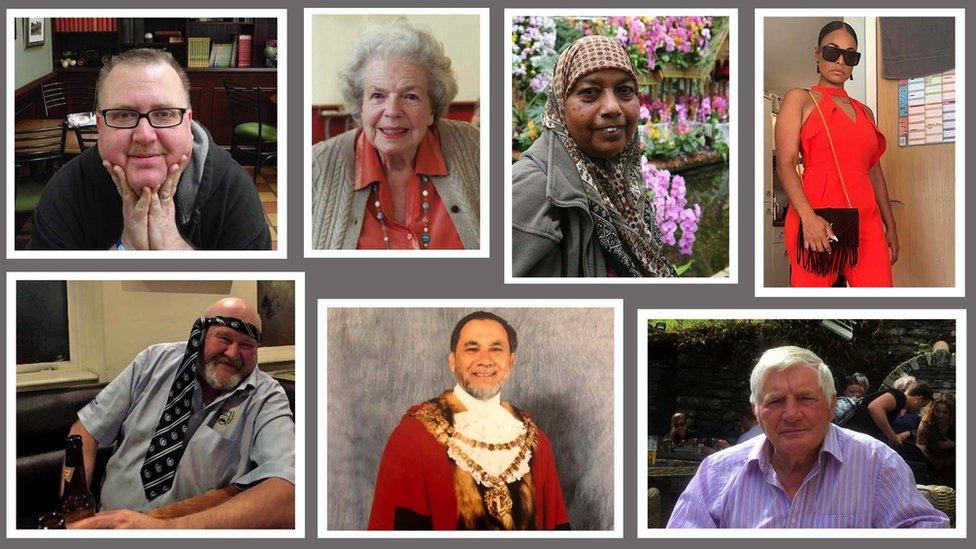

Prime Minister Boris Johnson wants all the over-70s, the most clinically vulnerable and front-line health and care workers to be offered a jab by mid-February, to allow the restrictions to be eased.

That requires about 13 million people to be given the opportunity to be vaccinated - but so far only one million have been.

And ensuring a quick rollout to the rest is fraught with difficulties.

There is enough vaccine in the country, BBC News has learned, but getting it into people's arms could be hampered by:

a global shortage of glass vials to package up the vaccines

long waits for safety checks

the process of ensuring there are enough vaccinators

How could a shortage of glass disrupt supply?

Two Covid vaccines have now been approved - one produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and another made by Oxford University and AstraZeneca.

The UK government has ordered 140 million doses - enough for the whole population.

The first hurdle is manufacture of the vaccine.

This involves two crucial stages - the production of the substance and then a process called fill and finish whereby the vaccine is put into vials and packaged up for use.

And there is already a concern about the latter stage, with the availability of key ingredients and equipment including glass vials a key issue.

England's deputy chief medical officer Prof Jonathan Van-Tam says fill and finish was a "critically short resource across the globe".

That is part of the reason why the amount of the two vaccines ready to go is more limited than ministers had hoped.

UK plants have made somewhere around 15 million or so doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine - that in itself is less than ministers said would be made at this stage (early in the pandemic they said there would be 30 million by the autumn).

But only four million have been through the fill-and-finish process.

The UK has used plants in Germany and the Netherlands to do some of this for the early batches.

But the government has also invested in a plant in Wrexham to ensure there is domestic capacity.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, meanwhile, is made outside of the UK - it comes from a plant in Belgium.

When it arrives in the UK, it has already been placed into vials.

But so far, fewer than five million doses have been delivered - less than half the number that should have been - because of problems with manufacture, including the fill-and-finish process.

However, the Department of Health and Social Care said it had been monitoring the supply chain for "some time" and was confident the arrangements in place for the supply and onward deployment of vaccines were sufficient.

Are the final checks taking too long?

Even once a vaccine is in the vials though, there is still one more step before the NHS can start using it.

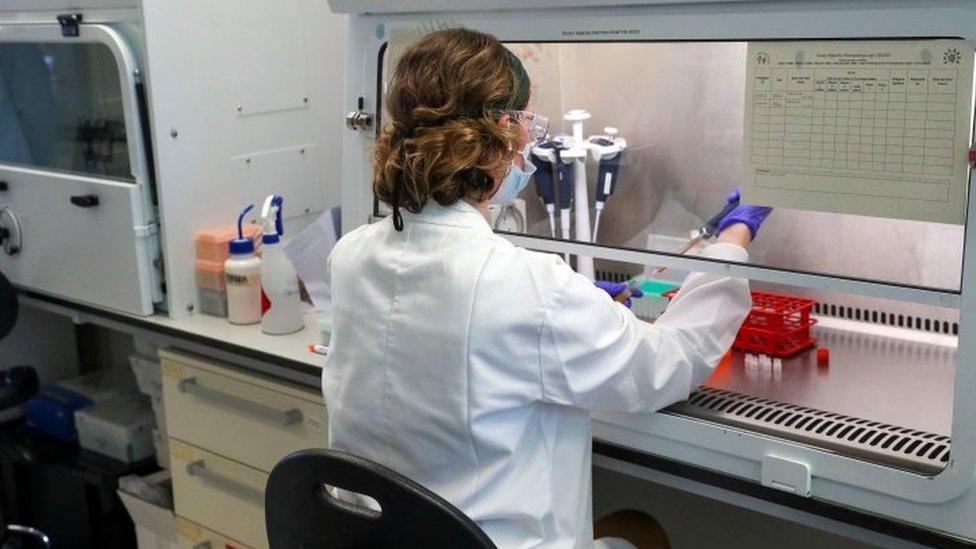

Each batch has to be checked and certified by the Medicines and Healthcare Products regulatory Agency.

And it can be several weeks before the vaccine can be given to the NHS to put in people's arms.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has called this a "rate-limiting factor".

About four million doses of the Oxford vaccine have been available for some weeks - they were put into vials last year - but as yet only just over 500,000 have been certified as safe to use.

Sources close to the NHS vaccination programme said this had been one of the key frustrations - saying it was taking up to 20 days for batches to be tested and released.

The MHRA said each batch had to be biologically tested for quality, while the manufacturer's documentation describing its production and quality-control testing process was reviewed.

Those close to the process say it does take a couple of weeks - and with more vaccine being produced, there is increased demand on the labs that do the work.

"You have to remember this is being injected into people," they said. "We cannot rush this."

Both vaccines have to go through this process.

What have hospitals, GP practices and racecourses got to do with it?

Once batches have been certified, they are ready to be distributed to the NHS vaccination centres.

Eventually, there will be a network of more than 1,000 local centres across the UK.

Currently, just over 700 are up and running.

These are being run from a wide variety of venues, from hospitals and large GP centres to community venues, racecourses and, perhaps in the future, conference centres and sports stadiums.

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

YOUR QUESTIONS: We answer your queries

GLOBAL SPREAD: How many worldwide cases are there?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

TREATMENT: How close are we to helping people?

The instability of the Pfizer-BioNTech has been well documented.

It has to be kept in ultra-cold storage and, once thawed, used within five days.

This has meant it is stored at major hospitals and gives the local vaccination centres just days to use up batches after they are delivered.

The Oxford vaccine, meanwhile, can be stored at fridge temperature, which makes it easier to distribute.

But even once they are at these vaccination centres, delivery of both vaccines is dependent on having the right numbers of staff available.

Currently, GPs, nurses, healthcare assistants and pharmacists are giving the vaccines.

But as the vaccination campaign ramps up, these will need to be supplemented by additional vaccinators.

Provision has been made to train other health professionals, from physiotherapists and dentists to dieticians.

But there are reports an "overload of bureaucracy" - including mandatory courses in fire safety and preventing radicalisation - is slowing down this training.

Ministers have said they will try to reduce the bureaucracy - amid warnings by the National Audit Office an army of nearly 50,000 vaccinators will be needed.

Although at the moment, there are thought to be enough staff to cope with the limited amount of vaccines available.

British Medical Association GP leader Dr Richard Vautrey said: "We will need support eventually but not now.

"At the moment, the biggest issue is the NHS having enough supply of the vaccine to give."

Can the UK hit its mid-February target?

Nearly a million doses have been given since people started to receive the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, in early December, which puts the UK third globally in the most vaccinations done per head.

And with the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine being used from this week, the NHS is hoping to double that number in the next seven days.

Government sources said there would be disappointment if it did not reach two million doses a week by late January.

That - and a little bit more - will be needed to hit the mid-February target.

But even then, and assuming most people in these priority groups have come forward, the impact would not be immediate.

It takes a few weeks for the immune response to kick in.

So it would be early March before the full impact of the vaccination of these priority groups is felt.

Then, however, it could have a significant effect.

Close to nine in 10 Covid deaths have been in these priority groups.

They will have had only one dose, which, for the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, is effective at preventing 70% of infections.

But the evidence suggests this will be enough to stop serious illness.

So if all goes to plan, the pathway to significantly easing restrictions comes into view.

But the complex nature of the supply chain coupled with the complexity of delivering vaccines to large numbers of people means it will take just one thing to go wrong to cause serious problems getting the UK out of this lockdown in the timeframe hoped.

Related topics

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020