Covid: The devastating toll of the pandemic on children

- Published

They are not likely to get seriously ill with Covid and there have been very few deaths. But children are still the victims of the virus - and our response to it - in many other ways.

From increasing rates of mental health problems to concerns about rising levels of abuse and neglect and the potential harm being done to the development of babies, the pandemic is threatening to have a devastating legacy on the nation's young.

'Closing schools closes lives'

The closure of schools is, of course, damaging to children's education. But schools are not just a place for learning. They are places where kids socialise, develop emotionally and, for some, a refuge from troubled family life.

Prof Russell Viner, president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, perhaps put it most clearly when he told MPs on the Education Select Committee earlier this month: "When we close schools we close their lives."

He says the pandemic has caused a range of harms to children across the board from being isolated and lonely to suffering from sleep problems and reduced physical activity - alongside school closures all children's sport is currently banned as it has been at various points during the pandemic. The only exception is for organised outdoor sport for the under 12s in Scotland.

Many experts are baffled by the approach to children's sport given the low risks of transmission outdoors and the clear benefits for emotional and physical wellbeing - the UK has some of the highest rates of child obesity in the world.

But it's not just the closure of schools. The stress the pandemic has put on families, with rising levels of unemployment and financial insecurity combined with the stay-at-home orders, has put strain on home life up and down the land.

The NSPCC says the amount of counselling for loneliness provided by its Childline service has risen by 10% since the pandemic started. Neil Homer, who has been volunteering for the service since 2009, has never known anything like it. "It's had a devastating impact," he says.

The experience of this 16-year-old is typical of the calls that come in. "I feel really sad and lonely. Most days I find myself just lost in my own thoughts and feeling numb."

Mental health problems on the rise

Unsurprisingly, there are clear signs the upheaval in children's lives is having an impact on children's mental health.

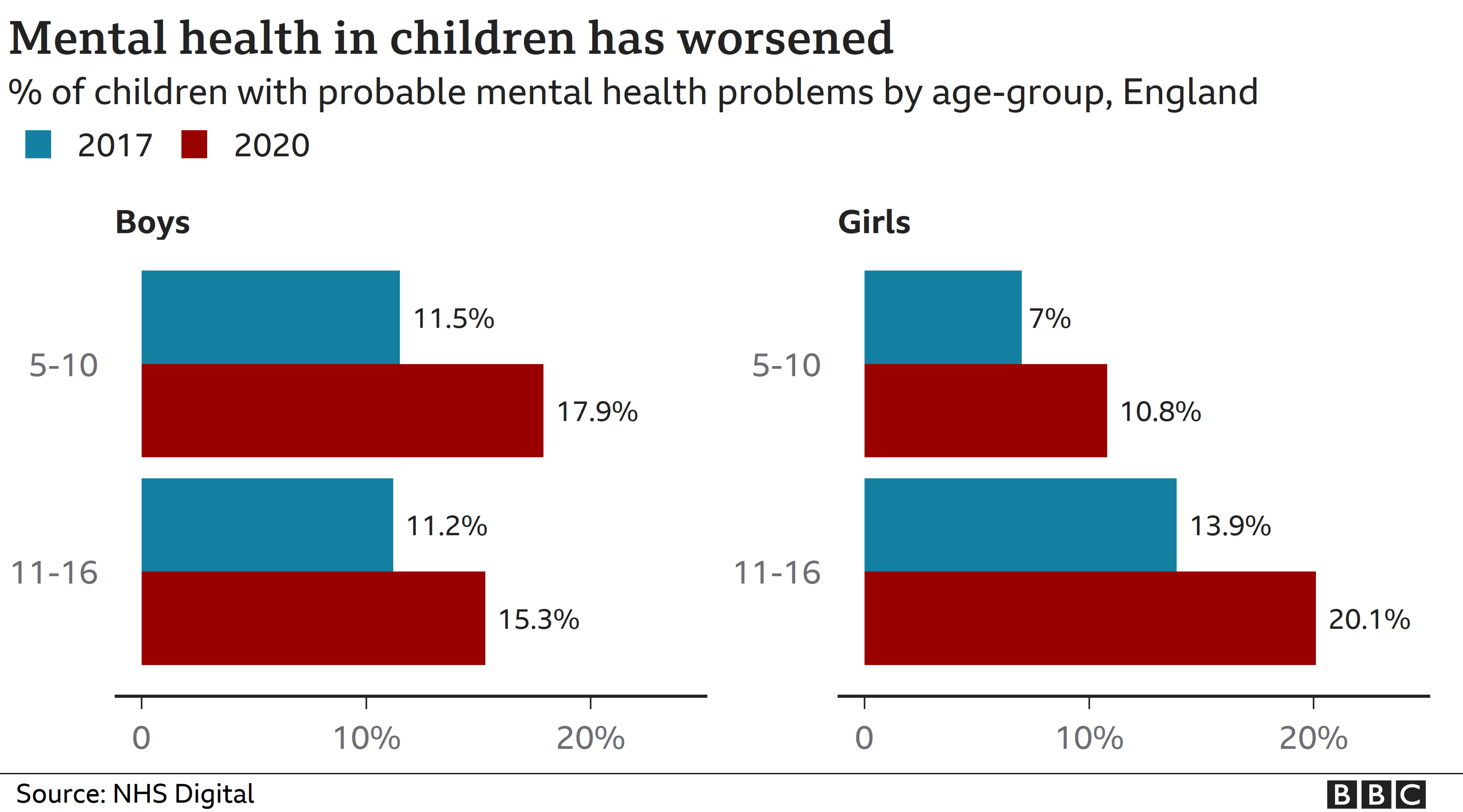

The Mental Health of Children and Young People in England 2020 report, external, which is produced by NHS Digital and the Office for National Statistics, is the official stocktake of the state of children's well-being.

It has been tracking more than 3,000 young people over the last four years. Its latest findings, published in the autumn, found overall one in six children aged five to 16 had a probable mental health disorder, up from one in nine three years previously. Older girls had the highest rates.

Children involved in the research cited family tensions and financial concerns as well as feeling isolated from friends and fear about the virus for causing their distress.

Older teenagers and adolescents have been affected too as they have seen their prospects shrink. The Youth Index, published in January by the Prince's Trust in partnership with YouGov, external, has been tracking the well-being of young people aged 16 to 25 for 12 years.

It found more than half of young people were always or often feeling anxious - the highest level ever recorded. Jonathan Townsend, of The Prince's Trust, fears young people are "losing all hope for their future".

Babies falling behind in their development

At the opposite end of the age spectrum, health visitors, who support parents and babies during the early years, are worried about the impact on newborns.

Research shows the first two to three years of a baby's life is the most crucial period of human development. This has become known as the 1,001 days agenda. If children fall behind, they can find themselves at a lifelong disadvantage.

The Institute of Health Visiting says services have been badly hit during the pandemic with these specialist nurses pulled away from their duties to help out on the Covid front line. In some areas, health visitor numbers have dropped by half.

This and the social distancing rules mean for a lot of parents the only support they have received has been online. Meanwhile, the absence of baby and parent groups, and the friendships that naturally develop from them, has meant the babies of the pandemic have not benefited from the stimulus of social contact that is vital to their development.

Alison Morton, head of the Institute of Health Visiting, says this has been an "invisible" cost of the pandemic, but one that will have a lasting impact, particularly in the most deprived areas. Babies and children, she says, are being "harmed" by what she says is the secondary indirect impact of the virus.

Children with disabilities 'incarcerated'

There are around one million children with special educational needs and disabilities - around one in 10 of whom have complex and life-limiting conditions, such as severe cerebral palsy or cystic fibrosis.

The nature of the pandemic and the response to it have created even greater challenges for many of these children and their families.

Those with the most complex conditions can require care at home from specialist nurses and carers. This has become harder to obtain as staff have been redeployed or charities forced to cut back on their support networks. For those with compromised immune systems, shielding has been a constant almost throughout.

Dame Christine Lenehan, director of the Council for Disabled Children, says in some cases children have ended up "incarcerated" in their homes. "There are some who have barely had any formal education since lockdown began."

She says even those who are the most independent have struggled, with many schools - she estimates more than half - unable to address the additional learning needs of children with special needs who are learning remotely.

Pandemic has made abuse 'invisible'

For some children, the pandemic has had dire consequences with the numbers being harmed and abused on the rise.

Between April and September there were 285 reports by councils of child deaths and incidents of serious harm, external, which includes child sexual exploitation. This was a rise of more than a quarter on the same period the year before.

But children's commissioner for England, Anne Longfield, is worried this is just the tip of the iceberg, arguing the lockdowns, closure of schools and stay-at-home orders have led to a generation of vulnerable children becoming "invisible" to social workers.

Referrals that would normally come in from a variety of sources, form health visitors to school nurses, dropped last year. This, she says, makes no sense given the impact of the pandemic on family life.

Figures show that before the pandemic there were already more than two million children in England and Wales living in households affected by one of the "toxic trio" - domestic abuse, parental drug and alcohol dependency or severe mental health issues. The fear is this will have risen significantly.

'Children have been abandoned'

The governments across the UK, of course, maintain they have prioritised children. Investment has been made in mental health services and schools are being prioritised as the first thing to open once lockdown starts to lift.

But is this enough? Research by Ms Longfield's organisation shows only one in three children who needed mental health support was getting it before the pandemic - and she believes that will now be even worse given the impact of the pandemic on both services and mental health.

She warns that children will be living with the legacy of the pandemic for "years to come", particularly those from disadvantaged communities, and wants to see a major investment in support for children.

Sunil Bhopal, an expert in child health at Newcastle University, agrees. He says too many people dismiss the impact on children, claiming they are "resilient" and will "bounce back".

He believes this is misguided and instead growing up in a world where even "playing with your friends is illegal" threatens to cause long-lasting damage to many. "I don't think it is an exaggeration to say children and their families have been abandoned."

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020