Covid trial in UK examines mixing different vaccines

- Published

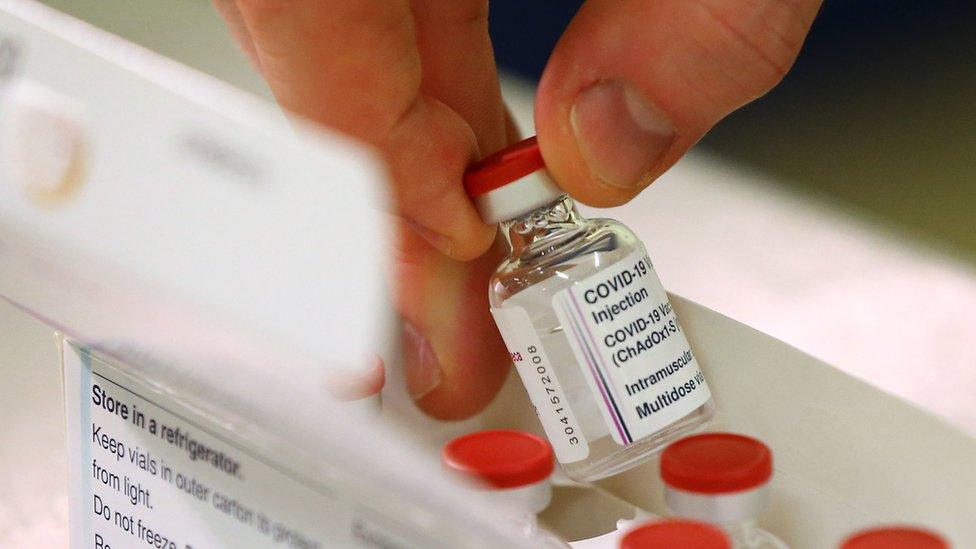

A UK trial has been launched to see if giving people different Covid vaccines for their first and second doses works as well as the current approach of using the same type of vaccine twice.

The idea is to provide more flexibility with vaccine rollout and help deal with any potential disruption to supplies.

Scientists say mixing jabs could also possibly give even better protection.

The vaccines minister said no changes would be made to the UK's current approach until at least the summer.

Currently, official guidance, external from the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) says anyone already given the Pfizer-BioNTech or Oxford-AstraZeneca jab as part of the UK's approved immunisation programme should get the same vaccine for both doses.

There is no suggestion this will change, although in very rare circumstances a different vaccine can be used, external - if only one vaccine is available, or it's not known which was given for the first dose.

Vaccines Minister Nadhim Zahawi said the government's taskforce had given about £7m to fund the study, but that findings would not be available until the summer and therefore "at the moment, we're not changing anything at all".

Previous experience suggests mixing vaccines could be a beneficial approach - some Ebola immunisation programmes involve mixing different jabs to improve protection, for example.

And Mr Zahawi told BBC Breakfast that this has been done with other vaccines such as jabs for hepatitis, polio and measles, mumps and rubella.

The Com-Cov study, run by the National Immunisation Schedule Evaluation Consortium, will involve more than 800 volunteers.

The study will be recruiting, external people aged 50 or older, who have not yet received a Covid vaccine, in London, Birmingham, Liverpool, Nottingham, Bristol, Oxford and Southampton.

Some will receive the Oxford jab followed by the Pfizer vaccine or vice versa, four or 12 weeks apart.

Other vaccines may be added as they are approved by regulators.

The chief investigator, Prof Matthew Snape from the University of Oxford, said the "tremendously exciting study" would provide information vital for vaccine rollouts in the UK and globally.

He told BBC Radio 4's Today programme that animal studies have shown "a better antibody response with a mixed schedule rather than the straight schedule" of vaccine doses.

"It will be really interesting to see if the different delivery methods actually could lead to an enhanced immune response [in humans]," he said, "or at least a response that's as good as giving the straight schedule of the same doses".

Why could mixing two vaccines boost protection?

While this study was initially designed to provide greater flexibility for vaccine rollouts, there is the tantalising possibility that mixing vaccines could provide even better, longer-lasting protection.

The Oxford vaccine, for example, uses a harmless virus - almost like a viral postman - to deliver the key part of the vaccine (the bit with coronavirus's genetic code) into the body.

This bit of code helps train the body's immune system to recognise coronavirus and prepare defences to fight it off in the future.

When a second dose of the same vaccine is given, there is some evidence to suggest that our immune systems can shift a bit of their focus onto the viral postman - rather than coronavirus itself.

The hope is that by mixing up jabs, this will allow our immune systems to focus more fully on building up protection against coronavirus.

Approaching the challenge using various vaccine combinations may strengthen results.

Other countries are conducting similar studies to monitor the impact of mixing vaccines.

Scientists will monitor volunteers for side-effects and carry out blood tests to see how well their immune systems respond.

The full study will continue for 13 months but scientists hope they will be able to announce some initial findings by June.

The study will also provide data on:

The impact of the vaccines on new variants

The effects of second doses at four and 12 weeks

WATCH: Pfizer v Oxford v Moderna – three Covid-19 vaccines compared

England's deputy chief medical officer, Prof Jonathan Van-Tam, said there were "definitive advantages" to learning whether or not vaccine doses could be mixed, given the "challenges" of the vast number of people needing a jab and potential global supply constraints.

He said combining vaccines could lead to better protection, "giving even higher antibody levels that last longer".

Any changes to the UK's current strategy would need approval from the JCVI.

OXFORD JAB: What is the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine?

YOUR QUESTIONS: We answer your queries

VACCINE: When will I get the jab?

NEW VARIANTS: How worried should we be?

COVID IMMUNITY: Can you catch it twice?

More than 10 million people in the UK have received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine.

The government aims to offer first doses to 15 million people in the top four priority groups, including everyone over 70 years old, by 15 February.

Mr Zahawi said after that target has been met, a detailed timeline will be set out for the next set of priority groups, including people aged 50 to 69.

LOCKDOWN LEARNING: Need some assistance with home-schooling? BBC iPlayer is here to help

THE ASK MARTIN LEWIS PODCAST: Why have workers missed out on government financial help during the pandemic?

What impact has Covid had on you and your family? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Related topics

- Published5 February 2021

- Published3 February 2021

- Published8 December 2020

- Published2 January 2021