Covid: Five reasons to be (cautiously) hopeful

- Published

The past few months have been awful. A surge in infections, tens of thousands of deaths and a damaging lockdown.

But there are now plenty of reasons to be, at least cautiously, hopeful that we are on the road to recovery. So what are they?

We are past the peak

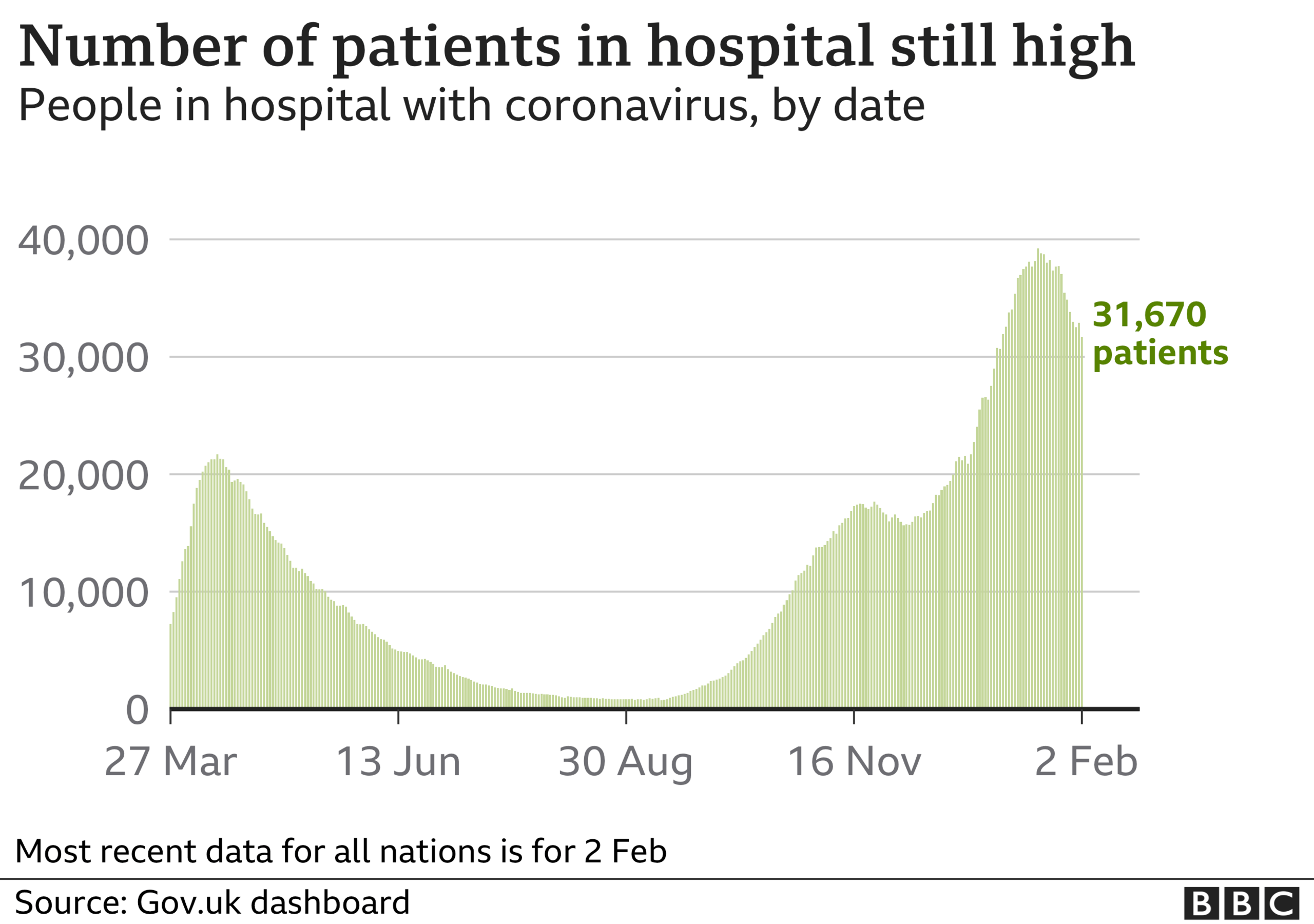

Infection levels have been falling since early January and, in recent weeks, that has translated into fewer people being admitted to hospital.

And now there are the first signs of the number of deaths coming down, albeit from a very high level, prompting UK chief medical adviser Prof Chris Whitty to acknowledge this week that the peak has been passed.

At the current rate, there could be fewer than 10,000 infections being reported a day in a couple of weeks. That would put the UK back to where it was in early October.

And by that stage, the drop-off in deaths and serious illness could start to become even more marked.

Vaccination programme going well

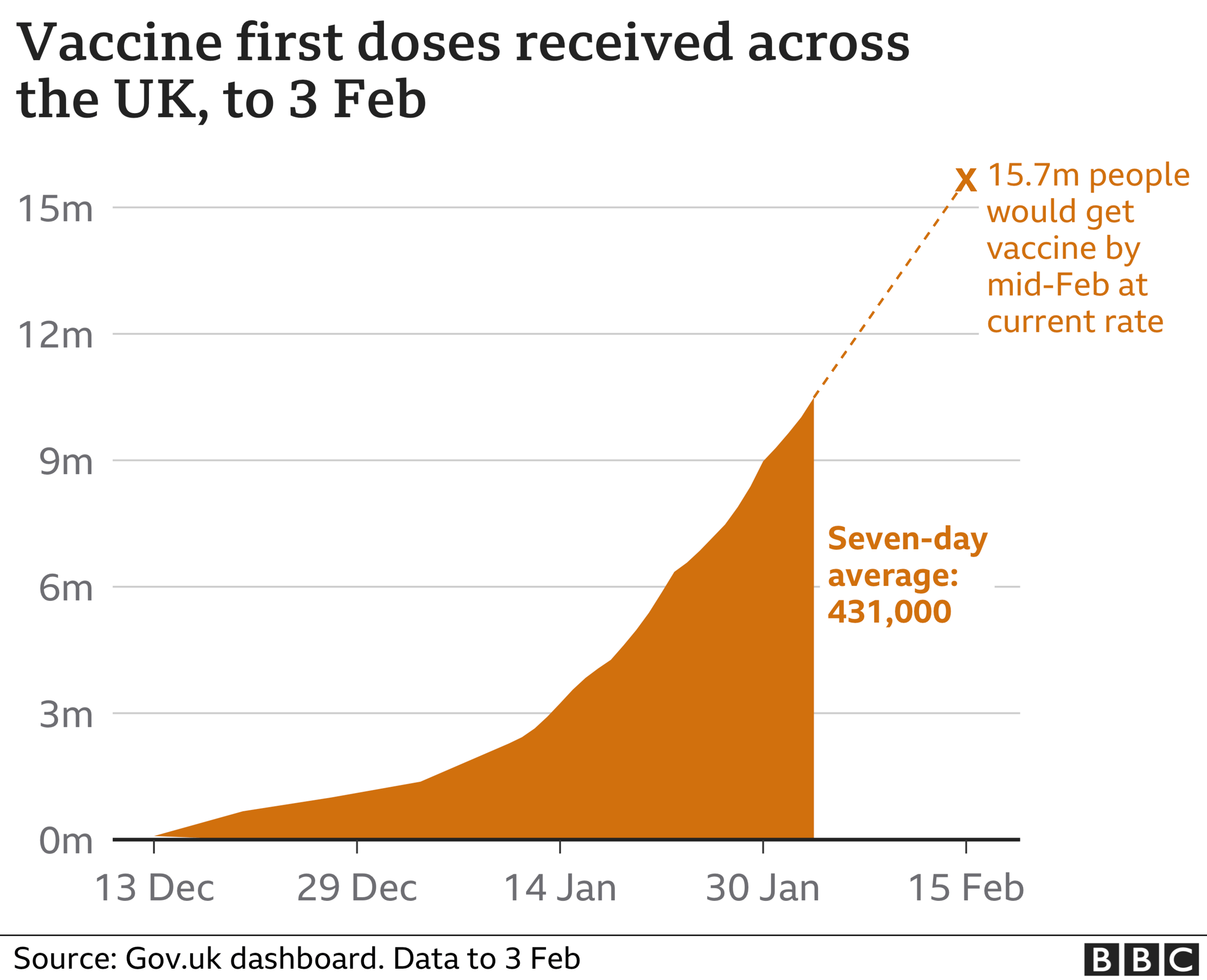

The UK has vaccinated more than 10 million people - more per head of population than almost anywhere in the world.

This puts the government well on track to hitting its mid-February target of offering all over-70s, health and care staff and the extremely clinically vulnerable a jab.

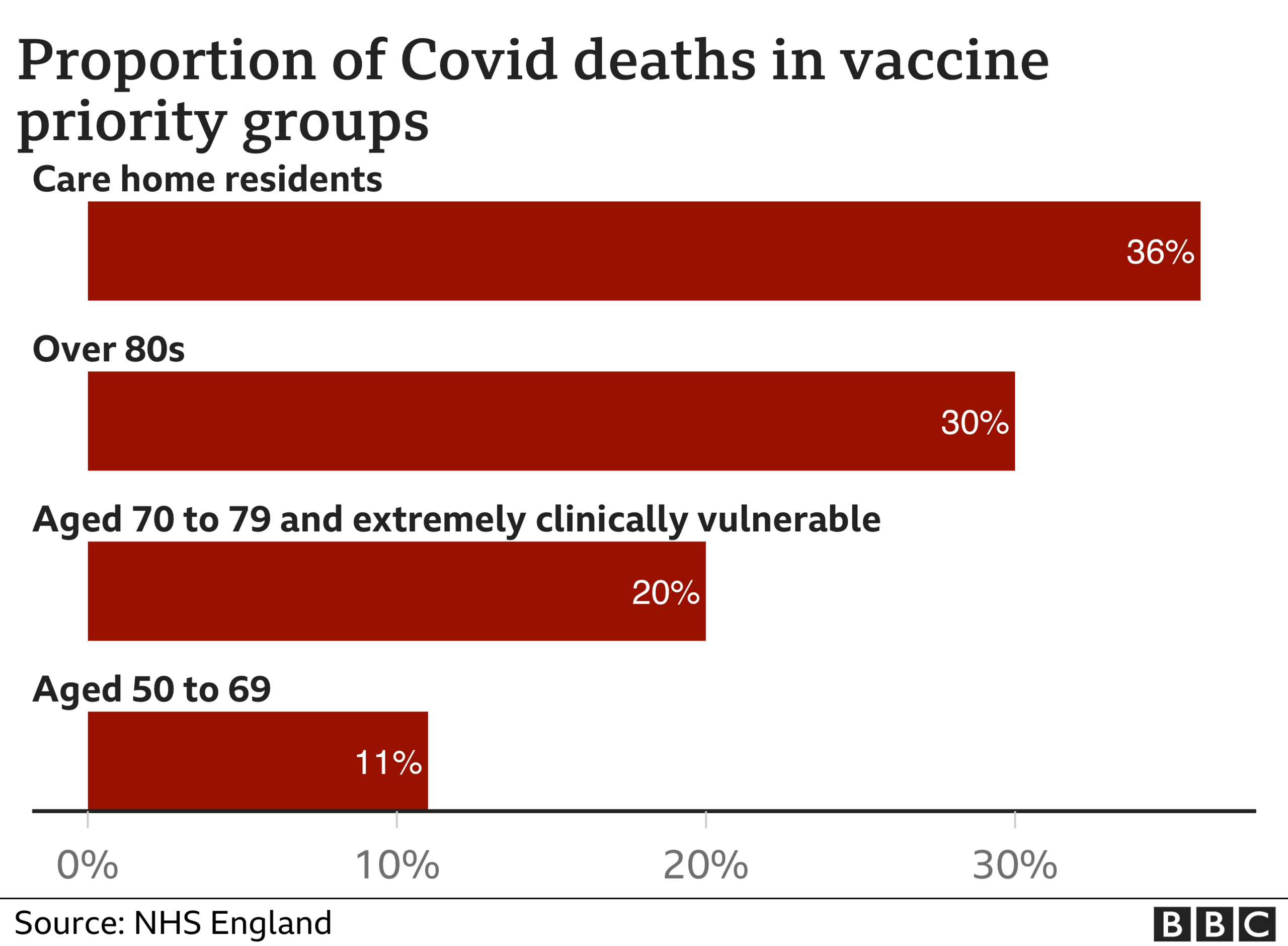

Most importantly about 90% of people over the age of 75 have been vaccinated. Given that three-quarters of Covid deaths have been in this group, that should soon start having an impact on serious illness and deaths.

But challenges do remain. There are signs that uptake in certain communities, particularly ethnic minorities, may be lower. And from the start of March, large numbers of people will start needing their second dose, which will result in a slowdown in the rate of people being vaccinated, unless supply increases.

That is possible. Pfizer, the manufacturer of one of the two jabs currently being used in the UK, is expecting to increase its speed of production after a slowdown in recent weeks.

The UK should also start to get its first supplies of the third jab approved for use, the one made by US firm Moderna, in April. But, as always, supply is fragile. Vaccine production is, after all, a biological process that requires vaccine to be grown. There are no guarantees.

Vaccination should slow the spread

As well as protecting the individual who has been vaccinated from developing Covid, there are growing signs the immunisation programme will also slow the spread of the virus between people.

In one of the trials - run by Oxford-AstraZeneca - participants were tested for the virus regularly after being vaccinated, rather than just relying on the development or not of symptoms as a sign of the vaccine working. This found that positive tests - so including those who were asymptomatic - reduced by 67%, suggesting the onward transmission of the virus would be significantly curtailed.

Scientists had always suspected this would be the case. But having some data means there can be greater confidence the spread of Covid should be dramatically reduced as the vaccination programme is rolled out.

Infection offers long-lasting protection

Another factor that will help reduce the burden of Covid is that so many people have now been exposed to the virus - and the latest research suggests they should have lasting protection.

A study by UK Biobank has been tracking the level of antibodies people have after infection. These help the immune system fight the virus and the research found 88% of people had them at least six months after catching the virus.

Prof Naomi Allen, the chief scientist who has been leading the research, described it as "really good news" as it suggested there was some degree of natural immunity. She said they would keep doing follow-ups to see just how much longer this lasted.

With estimates suggesting close to one in five people has been infected in the UK, that could mean there is a significant number of people with natural immunity - although even if you have been infected you are still advised to get vaccinated.

The mutations can be beaten

There has been a lot of concern about how the virus is mutating. The new UK variant is more transmissible than the virus last spring. And the South African variant, which now appears to be circulating in the UK, seems to weaken the effect of the vaccines.

But this does not mean the vaccinations are ineffective. Dr Susan Hopkins, from Public Health England, said this week she was still "happy" with the level of protection the vaccines appeared to give against the new variants, pointing to data showing 60% effectiveness rather than 80% or 90%. In other words, the vaccines still offer good protection, just not quite as good.

The other point worth bearing in mind is that when we talk about effectiveness we are talking about stopping symptoms developing. If we judge the vaccines by their ability to stop serious illness and death, the performance is much, much higher.

What is more, the Oxford-AstraZeneca team said they were confident updating their vaccine to make it work better against the mutations would be "very, very quick" and any trials needed would be small. So, from start to finish a new vaccine could be ready for rollout within months.

But this is only if it is needed. Viruses mutate so what is happening is not terribly surprising. Coronaviruses tend to be more stable than say flu, of which we see different strains circulating every winter. This is why some vaccine experts are saying there's no need to panic - a new vaccine may not even be needed.

So where does this leave us?

The next few weeks are bound to see a frenzied debate about how quickly the UK should unlock. This week it was reported Chancellor Rishi Sunak felt the aim of lockdown had been shifted from needing to protect the NHS to having to drive down infections close to zero.

Certainly early March will not signal a rapid return to normal. If nothing else, the NHS is likely to remain under quite some pressure. While cases are falling, the numbers in hospital are still 50% above what they were in the peak of the first wave.

On top of that, people in their 60s, who account for a significant number of hospitalisations, will still largely remain unvaccinated.

So what will be a more open question is what happens after that and how quickly - both in the short and long term.

By the end of March or early April, if all goes well, people in their 60s, and younger adults with health conditions, will have been offered a vaccine. Those in their 50s will follow soon afterwards. It means the groups where almost all the Covid deaths have happened will have had the chance of protection.

The seasons will also start working in our favour - respiratory viruses thrive in the colder, winter months. The unlocking could come quickly.

Then, looking beyond that, what about next winter? By autumn the whole adult population will have had the chance to get the jab. That won't mean the virus disappears. Not everyone will have taken up the option of a vaccine. And the jab won't have worked for everyone.

That is why, in the words of Prof Whitty, Covid will remain a "residual threat" for winters to come. Prof Paul Hunter, from the University of East Anglia, predicts we will see a rise in cases in the autumn - and says some measures, such as masks and maybe restrictions on crowded places, will be needed. But it will be nothing like what we have seen over the past year.

The war is not over, but the worst of Covid should be.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020