Coronavirus doctor's diary: Why are some of Bradford's elderly refusing the vaccine?

- Published

Mohammed Bostan, 95, is vaccinated in December

Covid vaccinations have been administered at pace in Bradford, as in the rest of the UK. But data for December and January indicates a high level of refusal among those aged 80 or over in the Pakistani community. Dr John Wright of Bradford Royal Infirmary asks why, and considers the implications.

By the end of January 67,000 people had received at least one Covid vaccination in Bradford including 82.5% of those aged 80 and above. It's an important achievement and a big step towards protecting the most vulnerable.

However, dig a little deeper and there are some concerning numbers in the data. While within the White British and Mixed-race British ethnic groups 87% of people in this age bracket have been vaccinated, only 46% of the 1,800 people aged 80 and over in the Pakistani community have been vaccinated - and 23% have refused the vaccine.

These figures are provided by GPs who have been calling people at home, and inviting them to come and get vaccinated. Among the 30% of those aged 80 or over in the Pakistani community who have neither been vaccinated nor refused the vaccine, it's likely that some - perhaps many - are undecided. I hope that we will yet persuade them to have the jab, because anyone who doesn't remains at risk as long as the virus is circulating, which is likely to be for some months yet.

It's too early to say whether the same pattern will be repeated for those in their 70s.

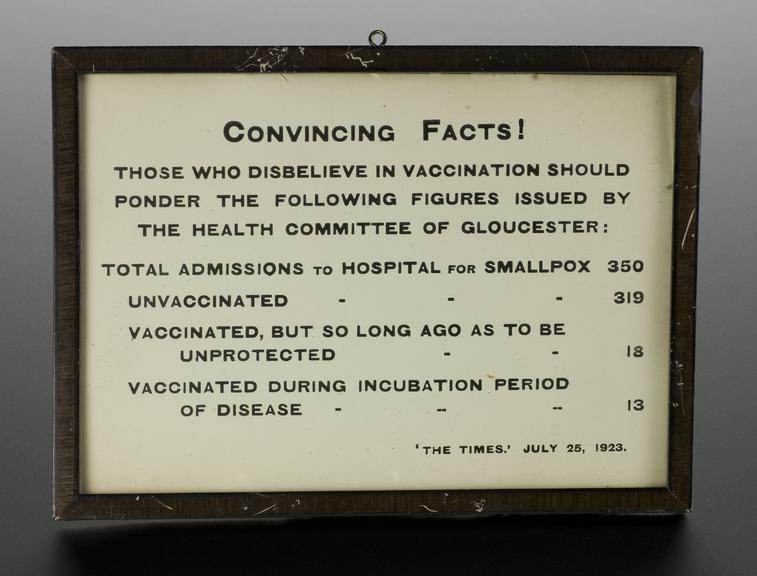

Vaccine hesitancy is nothing new. On the website of the Science Museum, external you can see a framed reproduction of some data about smallpox cases, published in the Times in July 1923.

"Convincing Facts!" it reads. "Those who disbelieve in vaccination should ponder the following figures issued by the health committee of Gloucester."

Below there is a small table. "Total admissions to hospital for smallpox - 350," reads the first line. And, under that, the key piece of information: "Unvaccinated - 319".

It is sad that the people refusing the vaccine today will be some of the patients with severe Covid in hospital tomorrow. The over-80s - the highest-risk group in society - will be in particular danger if they live in homes with younger people, who go back to work or resume social contacts when lockdown is lifted.

We were already aware, thanks to a survey by researchers, external at Born in Bradford and the Bradford Institute for Health Research, that South Asian and Eastern European communities were more likely to be unsure about the vaccine, or opposed to it, than others. Socio-economic status also plays a role, the researchers discovered, with these hesitant or sceptical attitudes more common in less well-off households.

Overall they found that 30% of people were ready for the vaccine and 10% would refuse it, with the majority undecided.

Interviews to explore these attitudes further, external showed that much of the hesitancy was nuanced and understandable. In many cases people realised that the vaccine was the only way out of this pandemic, but still had concerns.

Front-line diary

Prof John Wright, a doctor and epidemiologist, is head of the Bradford Institute for Health Research, and a veteran of cholera, HIV and Ebola epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is writing this diary for BBC News and recording from the hospital wards for BBC Radio.

Listen to the Coronavirus Front Line, on the BBC World Service

Or read the previous online diary entry: We're getting self-harming 10-year-olds in A&E

Some worried about safety, aware that this vaccine had been developed at speed - in 10 months rather than 10 years, which would be a more typical timeframe.

Maurice Hilleman, the famous microbiologist responsible for developing over 40 vaccines - including vaccines for Asian and Hong Kong flu - famously said that he only breathed a sigh of relief when three million doses of a vaccine had been given. Our respondents echoed his anxiety. But now that nearly 12 million doses have been given in the UK alone, the evidence is overwhelming: the vaccine is safe. We need to find a way of getting this information across.

Another group of people told the researchers that as they were young and healthy, and so unlikely to get serious illness from the virus, they didn't feel they needed the vaccine any more than they needed the annual flu vaccine. But while it's true that in most cases young people do not suffer badly with Covid, this ignores the risk of transmission to older relatives.

The researchers also found a loss of trust in the government due to mixed-messages and contradictory rules - and worryingly this mistrust appears to have crept over to the NHS. Traditional media outlets were also thought to be acting as government messengers, with the result that people turned to other less reputable sources of information. The spread of misinformation was more prevalent in the South Asian and Eastern European communities, perhaps because they have strong internal links.

Mufti Zubair Bult receives the vaccine at Whetley medical centre in Bradford

To combat this misinfo-demic, we are working with people from within BAME communities. Faith leaders have endorsed the Covid vaccine by having the injection themselves. On Thursday a pop-up vaccination centre will open in a mosque in Keighley. Hopefully it will be the first of many.

We have also set up a fantastic network of bright, young ambassadors from within the BAME community, to fight misinformation with truth. Very often those who are vaccine-hesitant have a limited grasp of the science; our ambassadors can help fill in the gaps in their knowledge, and provide reassurance.

Jordan Lee, a 20-year-old studying clinical sciences at the university of Bradford, is one of them. He notes that his own family are more inclined to trust rumours they find on social media than information from their GP's surgery. If anyone can persuade them to change their mind, it will be Jordan.

Sarah Hamaway, a student of pharmacy, has found that even colleagues in the chemist's where she has a part-time job have said they don't intend to have the vaccination. They've heard the rumours about the vaccine containing microchips, for example, and they are scared. She is trying to reassure them, and to correct these misconceptions.

With convinced anti-vaxxers the chances of success may be slim, but the ambassadors could have some influence with that large group of waverers.

Hamza Malik, another of the community ambassadors, says there is also some vaccine scepticism in his family

Tom Ratcliffe, a GP in Keighley, north-west of Bradford, points out that there's a risk that Covid will remain endemic in pockets of the population where there is a low uptake of vaccination. Nearly a fifth of the population of the area covered by the Bradford District and Craven Clinical Commissioning Group (which provided the data above about vaccine refusal) falls into the Pakistani/British Pakistani category, and it's a group, Ratcliffe notes, that has been more vulnerable to the virus than some others.

"This is a population at high risk and yet also at high risk of not being vaccinated," as he puts it.

One plan is to hold single-sex vaccine clinics, which may encourage women in the Pakistani community to get vaccinated.

He is also putting some faith in the pop-up vaccination clinic that will be held in the Keighley mosque.

"In multi-generational households we find that everyone needs to reach consensus. In our Pakistani communities we have to try and persuade key people in those family networks. We need to gain the trust in families and we hope that the clinics in the mosque will help with that," he says.

It could be that if the children of elderly first-generation immigrants can be convinced the vaccine is safe, then some of those in their 70s and 80s who have not so far responded to their GP's invitation will finally come forward.

Abdul Majid is waiting to see what happens to people who have the vaccine

One of the least-expected pockets of vaccine hesitancy Ratcliffe has discovered is within a group of about 50 street drinkers.

"They are largely living on the streets so they are very vulnerable," he says. "We run a clinic for them but again we have issues - they're refusing the vaccine and have bought into the crazy myths. Even though some of them inject all sorts of things, they won't have the vaccine."

Regular readers of this diary may remember Abdul Majid, a science graduate whose father, Abdul Saboor, has been in intensive care since October. He says a great variety of conspiracy theories are swirling around, generating much discussion in Bradford's Pakistani community. Some are saying they will have the vaccination, others that they won't. "At this present time I'm scared to take the vaccine," he says. "So, you know, I'm just waiting to see what reaction people get."

We must hope that as more people have the vaccination and show no ill effects, vaccine hesitancy will decline. And we must also continue with initiatives to reassure the undecided.

Follow @docjohnwright, external and radio producer @SueM1tchell, external on Twitter