Covid: Why goal is to live with the virus - not fight it

- Published

- comments

The government says it hopes to make Covid a manageable disease like flu.

Vaccination and new treatments, ministers and their scientific advisers argue, will reduce the death rate and allow us to live with the virus rather than constantly trying to fight it. Why are they doing this? And is it even possible?

Eradicating viruses is nigh on impossible

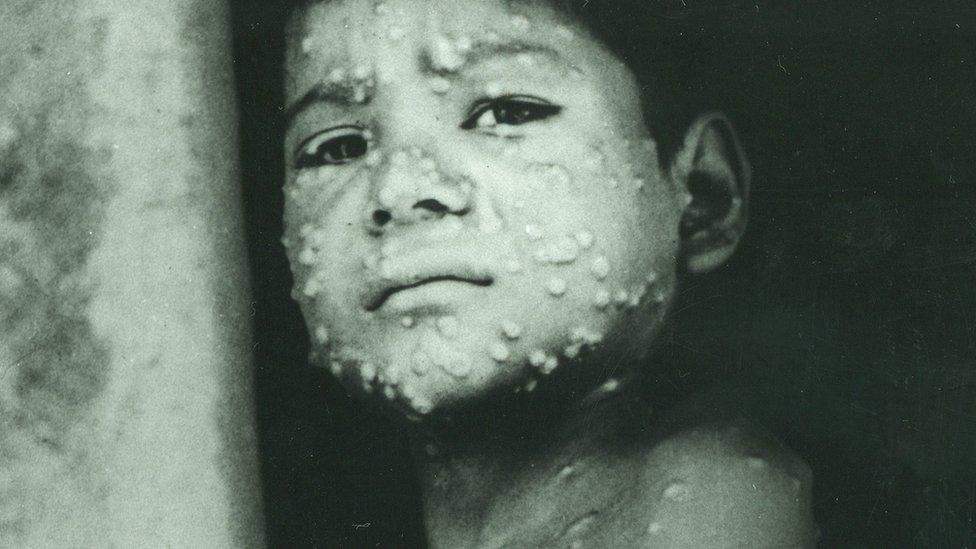

Wiping Covid from the face of the Earth would, of course, be great given the death and destruction it has caused. But the only problem with that is that eradication has only been achieved with one human virus before - smallpox in 1980.

It took decades to get to that point, and scientists and governments were only able to achieve this because of a pretty unique set of circumstances. Firstly, the vaccine was so stable it didn't need to be refrigerated, and when it was given it was immediately obvious whether it worked or not - a pustule developed.

It was also clear when someone was infected - a lab test was not needed, which was a huge advantage in trying to contain outbreaks.

Covid, as we are all too well aware, is completely different.

The 'Zero Covid' strategy

Instead, the so-called "Zero Covid" movement tends to talk about elimination. This basically means reducing cases to or close to zero in a territory and keeping them there.

One of the most high-profile advocates of this strategy is Prof Devi Sridhar, a public health expert from Edinburgh University. She believes we should treat Covid like measles, which has been largely eliminated in rich countries.

She argues that continued restrictions to get cases really low, coupled with a more effective test-and-trace system and vaccination, could mean we could keep it suppressed, allowing the UK to get back to a "somewhat normal domestic life" with restaurants, bars, and live sport and music events all possible.

But the price to pay, she says, would be border restrictions curbing international travel and "short, sharp lockdowns" when cases did inevitably flare up.

Dr Deepti Gurdasani, a clinical epidemiologist at the University of London, is another advocate of this strategy. She is one of more than 4,000 signatories of the Zero Covid petition, which is calling for a parliamentary debate on the proposal.

"Life could return to something like normal - we could even open travel corridors with other countries who have gone down that route," she says.

The problem with the measles approach

It maybe a tantalising prospect, but one that many believe is out of reach or would require such sustained restrictions that the economic and social costs would be huge. "Zero Covid is not compatible with the individual rights and freedoms that characterise post-war democracies," says Prof Francois Balloux, director of University College London's Genetics Institute.

Countries like New Zealand, Taiwan and Australia have achieved this because they were able to prevent the virus getting a foothold - and all the signs are that once their population is vaccinated, they will begin to lift border restrictions.

But no country which has seen the virus spread in the way it has in the UK has actually managed to then suppress it to the point of elimination.

Vaccines in theory provide a new tool to help us achieve that, as they have for measles.

But there is a significant flaw with this argument, says Prof Jackie Cassell, a public health expert from the University of Brighton.

Measles, she says, is an "unusually stable" virus. This means it does not change in a way that allows it to evade the effect of the vaccine. In fact, the same jab has essentially been used since the 1960s - and it also provides lifelong immunity.

It is already clear this is "sadly" not the case for this coronavirus, says Prof Cassell.

The challenge is keeping ahead of the virus

The variants that have emerged in South Africa and Brazil allow the virus to change to evade some of the immunity built up by vaccines.

The virus circulating in the UK has also mutated further to gain the key change - known as E484 - which allows this to happen.

As more people are vaccinated, this is only likely to increase. That's because mutations that are able to get around the immune response in some way will have a selection advantage, says Dr Adam Kucharski of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who has carried out research on global outbreaks from Zika to Ebola.

"We cannot get away from that. We may well need vaccine updates."

The challenge therefore is to "keep ahead of the virus", he says. But this is not, he believes, as hard as it perhaps seems given the media attention on the new variants.

Coronaviruses change less than flu, he says, which means the vaccines should still remain effective to a large extent.

What is more, the fact that the mutations that are being seen share some key characteristics gives us a good idea of the route they are going down. "You would expect it to be easier to update than it is for flu, where there are lots of different strains."

Although he warns utmost care must be taken at the moment as a population that is building immunity at a time when there is a lot of infection around provides an ideal breeding ground for variants to escape those vaccines.

He says it is too early to tell if we will get to the point where coronavirus can be treated like flu as we are yet to fully see the impact that the vaccines will have.

'De-risking' Covid could make it like flu

Such caution is understandable, as scientists want to see the evidence from the real world rollout of the vaccination programme first. A major study is under way from Public Health England looking at this - and it is expected to be published before restrictions are lifted.

But all the indications from the clinical trials and the experience of Israel, which is leading the world in terms of vaccinating its population, is that they will have a significant impact on infections - and where they do not, they will at least help prevent serious illness and its lasting "long Covid" complications as well as deaths.

For those who remain susceptible either because they refuse vaccination or the jab has not worked, advances in treatments that are being seen will be vital.

It suggests we can get to the point - in the word's of England's chief medical adviser Prof Chris Whitty - where we "de-risk" Covid.

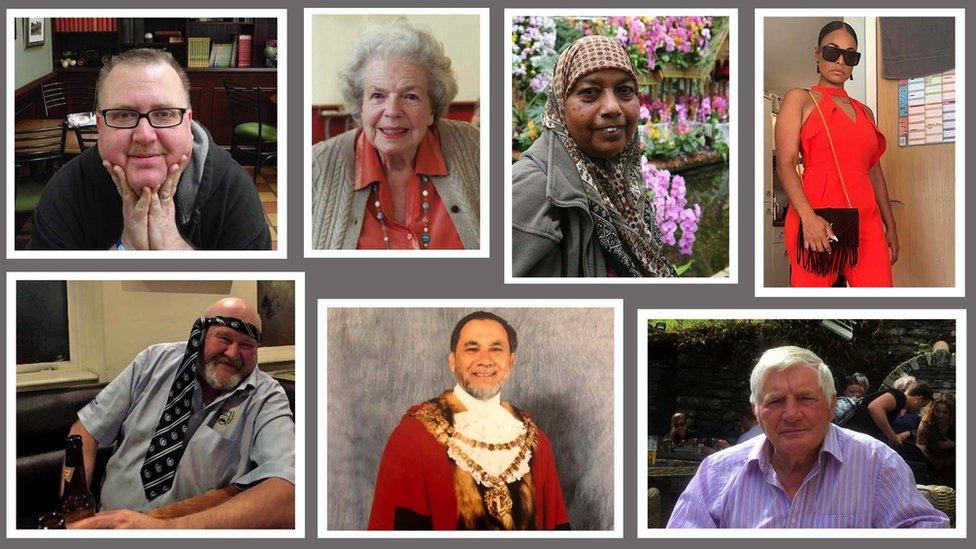

That does not mean no-one will die. Prof Whitty has talked about getting to a "tolerable" level of death. And certainly many expect next winter will be challenging with particular concern the most deprived communities will be hit hardest amid fears vaccination uptake has been lowest in these areas.

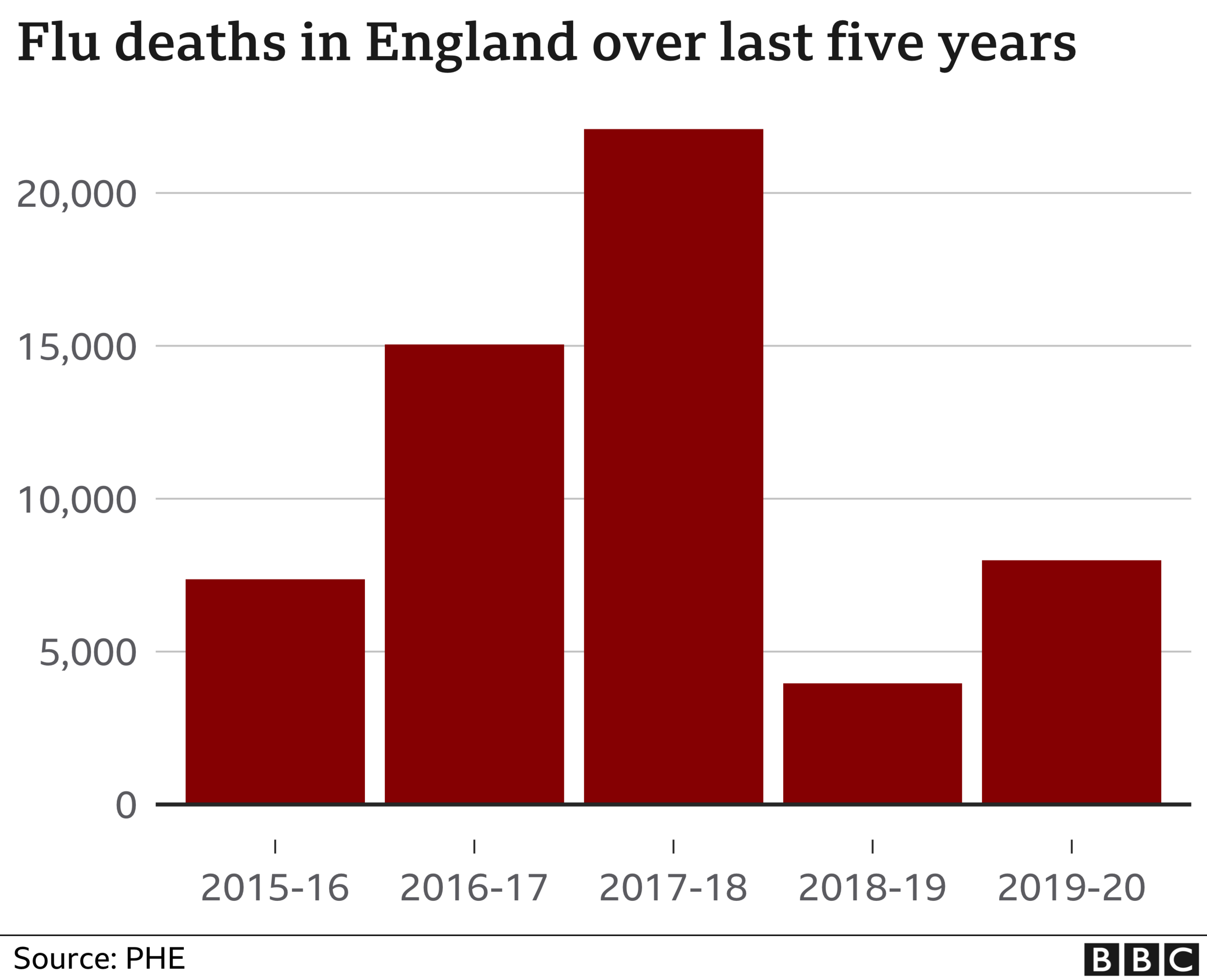

But it is easy to forget that flu can also kill on quite a scale. Back in 2017-18, more than 20,000 people died from it.

It was a harsh, cold winter and deaths from other causes such as heart disease and dementia rose too, pushing excess winter deaths close to 50,000. Society barely blinked.

"We have lived alongside viruses for millennia", says Prof Robert Dingwall, a member of the government's New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Group. "We will do the same with Covid."

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

LOCKDOWN RULES: What are they and when will they end?

OXFORD JAB: What is the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine?

VACCINE: When will I get the jab?

NEW VARIANTS: How worried should we be?

Related topics

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020