Child heart transplants: Record year for new-style operations

- Published

Fourteen-year-old Freya Heddington was one of the first recipients - and says she's "ecstatic"

Two UK hospitals have teamed up to offer a novel type of heart-transplant service for children, reducing waiting times for the life-saving operations.

In the programme, so-called "non-beating donor hearts" are revived to give to teenage recipients.

Freya Heddington, 14, from Bristol, was one of the first to get one, waiting just two months instead of two years.

Despite the pandemic, 2020 was one of the busiest years in a decade for heart transplants in children in the UK.

In 2015, the Royal Papworth Hospital in Cambridge became the first in Europe to retrieve and transplant adult donor hearts that had been allowed to stop beating on their own after life support had been withdrawn.

By using a special device, surgeons can effectively restart the heart and keep it healthy until transplantation.

Last February, the hospital collaborated with Great Ormond Street hospital (GOSH) in London to extend the service to children.

Until then, almost all paediatric heart transplants came from patients who had suffered brain death, where although their heart might beat, they would never wake up. Once life support is withdrawn, the heart is stopped and retrieved; also known as donation after brain death (DBD).

'I am ecstatic I got such an amazing gift'

Freya, 14, was one of the first paediatric patients to undergo this type of heart surgery.

In August 2019, she was diagnosed with restrictive cardiomyopathy, which can cause tiredness, chest pain and breathing problems.

She was warned she might have to wait up to two years for a heart, but the programme run by GOSH and Royal Papworth meant she had to wait only eight weeks.

Freya left hospital 10 days after her operation and within months could start doing the things she loved most again, like horse riding.

"I now have more stamina. I can go out for long walks and climb hills and I don't need to stop for breathers," she says.

"I am ecstatic that I got such an amazing gift, but it's upsetting to know that someone also died."

Freya's dad, Jason, says their family will never forget the people - and the machine - that saved her life.

"Freya needs medication on a daily basis and there are hospital visits. It'll always be in the back of our minds," he says. "But we know now she's got a lovely, healthy heart and her future is bright."

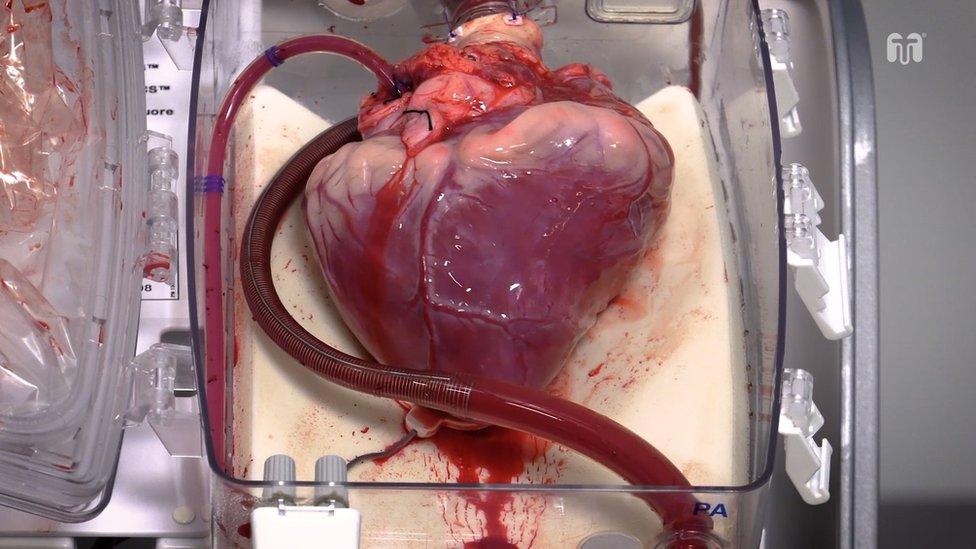

A heart sits in an organ-care-system machine, which makes it beat outside the body

How does donation after cardiac death work?

For many years, non-heart-beating donation was deemed unsuitable for transplantation due to the damage sustained from oxygen deprivation when the heart stops.

However, a specially designed machine, called the organ care system, can help keep it beating outside the body.

The heart can be transferred to the device once life support is withdrawn, the heart has stopped beating on its own and death has been confirmed.

Blood, nutrients and oxygen are pumped through the organ for up to 12 hours, allowing time to carry out vital checks and even transport it to other hospitals for transplantation.

A donor family's consent is always required before any surgery.

Freya has her stamina back and is able to climb hills again

'Devastating' wait for families

Usually, children have to wait around two-and-a-half times longer than adults for a donor heart.

The UK has only two paediatric heart-transplant units - at GOSH and at Newcastle's Freeman Hospital - and in the past five years, 39 children died before a donor heart became available.

"Some patients will just not survive the wait, says Jacob Simmonds, a transplant surgeon at GOSH. "There is also a risk that while waiting they could damage other organs, particularly the lungs."

The GOSH and Royal Papworth collaboration resulted in six of the new type of paediatric heart transplants - donations after cardiac death - in the UK in 2020. Only four others have been carried out worldwide.

Overall, 32 paediatric heart transplants were carried out last year - the second most in a decade.

"We didn't believe during a pandemic we would achieve a record number of transplants. It was a phenomenal team effort," says Marius Berman, surgical lead for transplantation at Royal Papworth.

The Royal Papworth team: Simon Messer, transplant surgeon. Marius Berman, surgical lead for transplantation. Jen Baxter, lead nurse for organ retrieval

The six transplants came from adult donors because the organ care system can accommodate hearts from donors weighing more than 50kg (eight stone).

Royal Papworth and GOSH are now developing a new piece of technology which they hope will mean they can retrieve hearts in the same way from children.

If successful, it could increase the number of organs available for infants and even babies, where there is a desperate shortage.

- Published23 March 2020