Covid: Why can't we unlock more quickly?

- Published

The vaccine rollout is going well and cases have plummeted since lockdown began at the start of the year.

And yet the road out of lockdown in England and elsewhere in the UK is slow and gradual.

Ministers say they want to closely monitor the impact of each step before moving on to the next one. It is a process which will take four months at least.

Why is the government being so cautious?

There can be no more steps backwards

A key mantra in the lead up to the announcement is that each step forward must be irreversible. There must be no steps back.

But despite falling infection rates, the number of new daily cases still remains relatively high compared to summer and early autumn. It is still a very delicate position.

Plus ministers have certainly been stung by the problems of last year, when the first unlocking saw areas in the North West and Midlands having restrictions quickly re-imposed.

Then, during the autumn, some areas found themselves constantly moving up and down the tiers.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson is adamant such chopping and changing cannot happen again. "What we want to see is progress that is cautious, but irreversible."

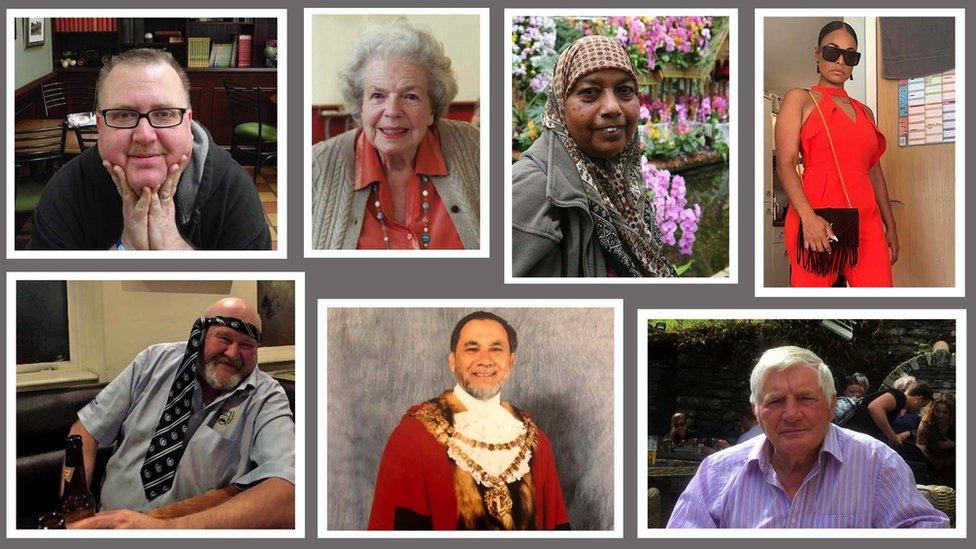

Many vulnerable not yet protected by vaccine

The government has achieved its target of offering everyone over the age of 70 a jab by mid-February.

It means by the time schools open, the most vulnerable people in society should have built up a fair degree of immunity. But that still leaves significant numbers at risk.

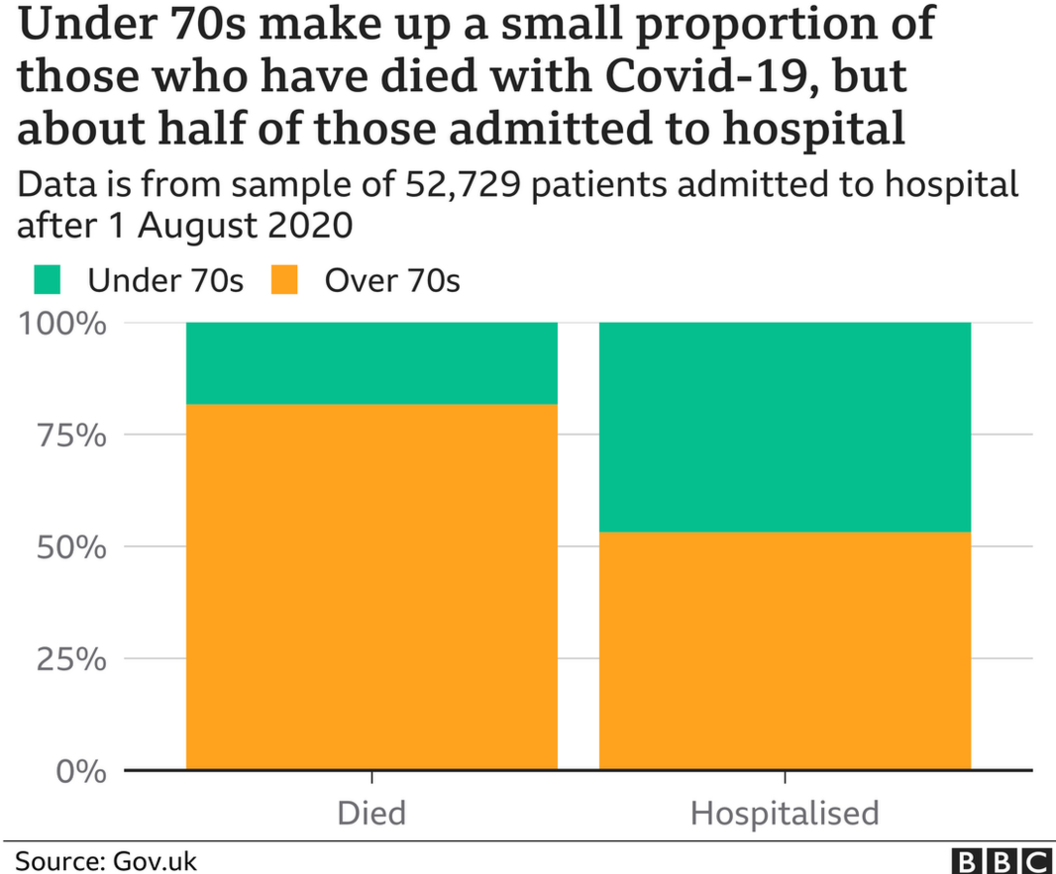

Nearly half of those admitted to hospital with Covid are under 70.

And with the numbers in hospital only just below the level they were at during the peak in the first wave, the NHS is not yet out of the woods.

Schools could drive up infection rates

Schools are not considered a significant driver of infection. Cases still fell in November when England was in lockdown but schools remained open.

But there is still a concern re-opening them for all pupils could push up the rates. One of the big unknowns is the new more contagious variant which was not dominant back in November.

Research by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, external has predicted re-opening schools for all could push the R number - the average number of people an infected individual passes the virus on to - above one, prompting a growth in cases.

The break at Easter will provide an opportunity to assess the impact of the move - and is why ministers resisted calls to only send some year groups back.

Infection + vaccination = ideal breeding ground for mutations

Mutations are to be expected. Growing levels of immunity from further rollout of the vaccine will favour variants that can sneak past the vaccine.

That is because of what is known as selection advantage. Viruses change all the time, and the mutations that have an advantage will spread more easily.

In the future, when the population has a lot of immunity, mutations that can evade some of the immune response will be in a stronger position to spread.

That does not mean the mutations will render the vaccines completely ineffective - coronaviruses are more stable than flu, with which we see different strains circulating each year.

But experts have warned everything must be done to guard against mutation at such a delicate time.

Vaccinating when there is a lot of virus circulating is pretty unusual. Normally vaccines are given ahead of exposure.

Scientists believe having high levels of infection at a time when people are building up immunity will encourage mutations even more than normal. That, they warn, would be foolish.

Quick unlocking could lead to surge in deaths

Modelling carried out for the government by Imperial College London has looked at what would happen if there was a quick unlocking.

It suggested if restrictions were lifted by the end of April, there could be a surge in deaths in the coming months.

And by next summer another 80,000 Covid fatalities could be seen.

The government's chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, says: "The sooner you open up everything, the greater the risk of a resurgence. The slower the better."

But such modelling is by its very nature full of uncertainty, because of the assumptions that have to be made.

For example, this modelling has not taken into account seasonality.

Would there really be a surge in the summer when people are outdoors and respiratory viruses tend not to thrive?

It is a risk ministers are simply not prepared to take.

Could cautiousness haunt government?

In taking this approach, though, it is quite conceivable the government could quickly find itself under pressure.

The restrictions will continue to have a huge impact on people's lives and livelihoods for months to come.

If re-opening schools does not prompt a rise in cases, if the warmer weather helps and the vaccine impact really begins to kick in, infections and hospital admissions could fall to very low levels.

A key phrase used in the lead up to the roadmap being unveiled was the importance of "data not dates".

That works both ways.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020