Covid: Intensive-care patients moved hundreds of miles

- Published

One patient was moved from Surrey to Tyne and Wear, data shows

Two patients were moved to a hospital 300 miles away, because of intensive-care bed shortages during the second UK coronavirus wave, BBC News has learned.

An unprecedented 2,300 intensive-care patients moved between UK hospitals from September 2020 to March 2021, in search of beds, data shows.

Front-line doctors, speaking for the first time, say these transfers were the only way to care for patients.

NHS England said the health service had responded well under intense pressure.

In January this year, the UK's four chief medical officers put out a joint statement saying: "Without further action, there is a material risk of the NHS in several areas being overwhelmed."

And measures were taken to cope with the increased demand:

The number of intensive-care unit (ICU) beds across the UK almost doubled

Staff were borrowed from other departments

In some hospitals, senior doctors acted as nurses

But ICU staff reported specialist nurses, who normally look after one patient each, were caring for three, four or - in one instance - five.

And data from the UK's Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) shows almost three times more patients than usual were moved to different hospitals - sometimes hundreds of miles away from their home.

Between September 2018 and March 2019, in comparison, there were just 789 such transfers.

Dr Mamoun Abu-Habsa says patients are transferred when it is "the only option"

In London, one of the "hotspots" for transfers, doctors set up their own schemes to organise the movement of patients.

Critical-care consultant Dr Mamoun Abu-Habsa was instrumental in setting up a pandemic transfer service before the second wave hit.

Foreseeing the pressures ICUs could face, he sourced an ambulance and equipment, and trained nurses and doctors so they could accompany patients being transferred.

Where hospitals were close to capacity, Dr Abu-Habsa said, moving patients made a huge difference to their care.

'Absolutely life-saving'

"We were taking patients across from hospitals that were close to their critical levels of oxygen supply, or the last ventilated bed, to hospitals that were under somewhat less pressure," he said.

"That was absolutely life-saving."

Few NHS staff have been prepared to speak out about the extent of patient transfers during the second wave, because of the sensitivities around moving such fragile patients because of bed shortages.

But Dr Abu Habsa wants people to know how carefully the transfers were handled - and why doctors felt they had no choice.

"No-one wants their patients to be taken away from them to complete their journey of care at another centre," he told BBC News.

"That's not how you are wired as a medical professional.

"But they were also very acutely aware that under the circumstances the particular hospitals were under, that was the only option to preserve access to life support."

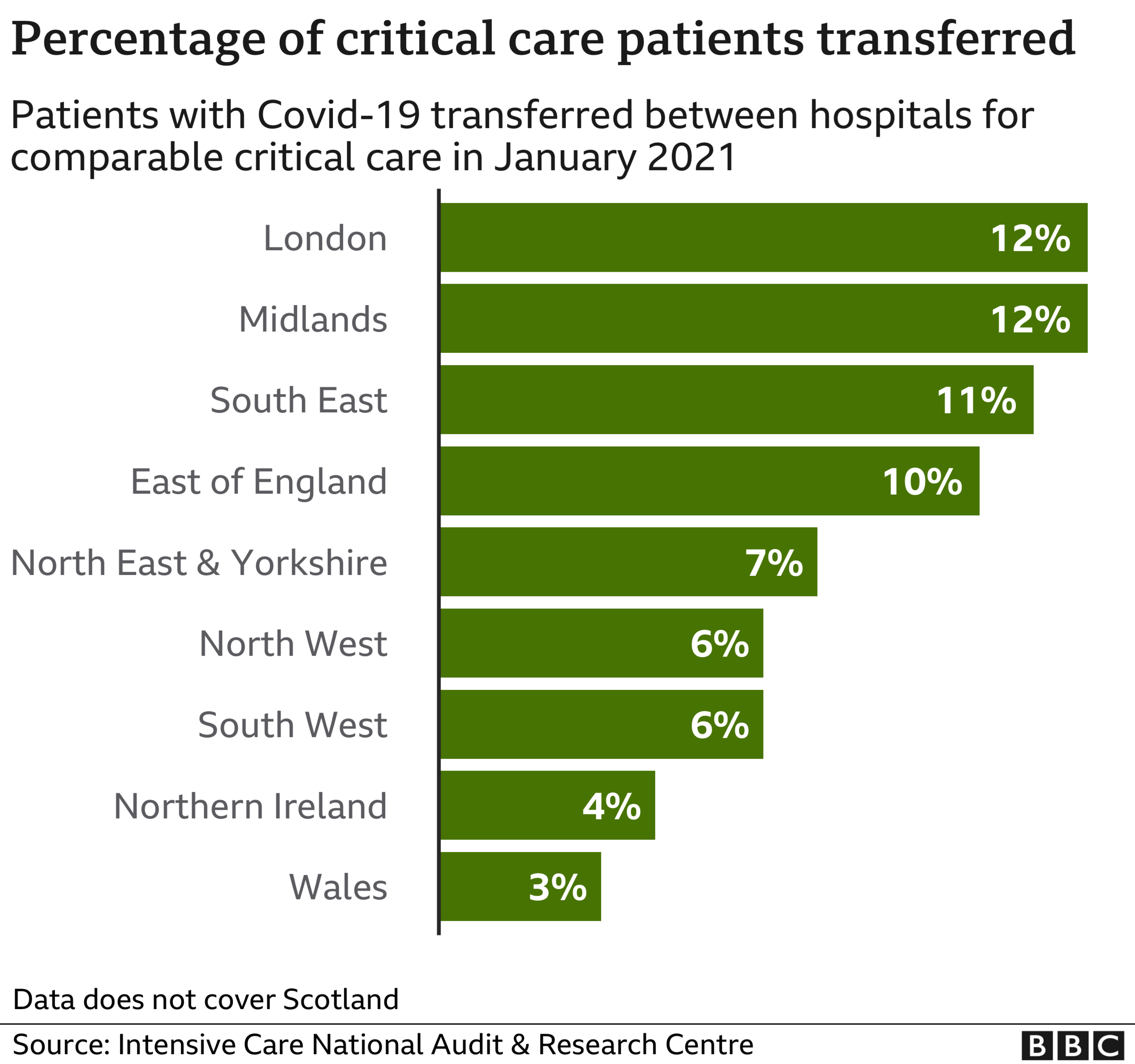

The latest figures show one in eight patients had to be moved from hotspots in London and the Midlands, with more than a quarter of these travelling long distances.

Among the furthest were:

West Midlands to Devon - 160 miles

Birmingham to Newcastle - 200 miles

Surrey to Tyne and Wear - 300 miles

In January, the lord mayor of Stoke-on-Trent's chauffeur, Ashley Harvey, was admitted to the city's hospital, with severe breathing difficulties due to Covid-19.

Days later, despite being in an induced coma and on a ventilator, he was transferred to Salford hospital - one hour away.

His family say they were told it was to make room for a surge of patients coming up from the South.

Ashley Harvey was moved from Stoke-on-Trent to Salford

"I'm aware that they had nine patients come from London, who were having a displacement of patients coming into the hospitals up and down the country - somebody would have made a difficult decision," Mr Harvey said

His daughter Louise was home from university when the family were told Ashley was being moved.

"They were saying that he was well enough to do that journey - and make space for someone that's worse," she said.

"It's insane to think that someone could be worse, because he was very poorly," but that "sort of gave us a bit of hope", she added.

In Birmingham, Dr Nitin Arora, a leading member the Intensive Care Society, said, at the worst point, 40% of ICU patients in some hospitals had to be moved - and without the transfers, more people would have died.

"We would have seen scenes like in Italy, triaging by age, scenes like New York, where some hospitals had mortality rates five times higher than others because they were working on a seven-to-one ratio," he said.

"The transfer service was one of the winners in this pandemic."

Without the transfers, Dr Nitin Arora says, more people would have died

The UK has a relatively low proportion of intensive-care beds compared with similar countries - and the pandemic pushed that capacity almost to the limit.

Dr Abu-Hapsa says that must now change.

"The shortage of critical care beds in the UK was absolutely felt during the pandemic," he said..

"There were contingencies in place to redistribute the pressure load from London to other parts of England - but none the less, the reality remains we were very close to breaking point."

An NHS official said: "Each patient transfer only occurred after direct agreement between intensive-care clinicians and senior doctors that it was safe and right to do so and always happened under the supervision of a specialist transfer team.

"Being able to provide mutual support in this way is one of the advantages of having a truly national health service and prevented regions being overwhelmed, as happened in some other countries, even when our hospitals admitted more than 100,000 Covid patients in a single month."

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

YOUR QUESTIONS: We answer your queries

TREATMENTS: What progress are we making to help people?

EPIDEMIC v PANDEMIC: What's the difference?